Vietnamese Chinese

What Makes Chinese so Vietnamese?

An Introduction to Sinitic-Vietnamese Studies

(Ýthức mới về nguồngốc tiếngViệt)

DRAFT

Table of Contents

dchph

Chapter Two

Several issues will be addressed in this chapter. Firstly, to defuse the misconception about the Vietnamese language as being descended from common Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer (AA MK) languages, my new discoveries in both Sino-Tibetan and Sinitic etymologies for the Sinitic-Vietnamese vocabularies with my newfound proofs of over 400 basic and fundamental words that will revigorate the Sino-Tibetan theory. Secondly, for those that make up almost all of Vietnamese vocabularies I will elaborate on what was brought up in the introductory chapter by devoting a portion of this research on introducing two new approaches that have been utilized in the process to unveil those hidden Sinitic-Vietnamese cognates that the Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer specialists may not be aware that they even exist, and identify common linguistic characteristics of the Vietnamese and Chinese languages both share. Besides, this whole academic matter will also expose the disguise of "nationalism" that is politically motivated to the bias of linguistic classification.

II) Rainwash from the Austroasiatic sky

The usage "rainwash" herein, besides the contextual connotation of "brainwash", points to the fact that "torrential" precipitation will purge unwanted poluted particles back to the earth, that is, old imprinted marks on human long-term memory that would hardly fade away. That has once happened to the Sino-Tibetan classification of the Vietnamese language in the early decades of the last century. Meanwhile the Sino-Tibetan theory has undergone constant rectifications that Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer theorists have never missed a beat that selectively aimed to eliminate what was left missing in the Sino-Tibetan family. By then the theory still lacked cognates of basic words in Vietnamese to support the theory, which is no longer the case by now.

When readers start to read about the Chinese etymology of Sinitic-Vietnamese words in this research, they mostly have already formed their own answer regarding to the question of whether Vietnamese is a Sino-Tibetan or Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer language. Every story has at least two sides of it and both likely overlap each other, of which they may not even know that they exist. In our specifics, be that of Mon-Khmer or Sinitic language family, even if issues of ether side exists in theory only, the truth lies somewhere in between. What we do not know does mean they do not exist. As far as the Sino-Tibetan etyma are concerned, I am showing what I have learnt about it with the theory that modern Vietnamese had roots from the China South region and it was also where the Chinese language had grwon matue to its full term.

As a matter of fact the homehand of all Southeast Asian languages originated from the same area as that of Vietnamese. Meritt Ruhlen in his book entitled The Origin of Language (1994. p. 143) points out that

"[t]he Austric family of Southeast Asia consists of four subfamilies: Austroasiatic, Miao-Yao, Daic, and Austronesian, the last two of which apprear to be the closest to each other. The Austroasiatic sub-family consists of two branches, Munda and Mon-Khmer. The small Munda branch is restricted to northern India while the Mon-Khmer branch, more numerous in both languages and speakers, is spread across much of Southeast Asia, often interpersed with languages of other families. Vietnamese and Khmer (or Cambodian) are the two best known Mon-Khmer languages."

[...] "The Daic languages, of which Thai and Laotian are the two best known and the only ones to achieve the status of national languages, are found in Southern China, nothern Vietnam, Laos, and Thailand. Austronesian languages are found on Taiwan, which is probably the original homeland of the family, but also on islands throughout the Pacific Ocean, and even on Madagascar in the Indian Ocean close to Africa. The present of Chinese domination of Taiwan is a consequence of a recent migration from the mainland that began in 1626. Over six millennia earlier a previous migration from the mainland, of people closely related to the Daic family, had led to the original Austronesian occupation of the island, which turned out to be the small step in what was one the longest — and most hazardous — migrations in human history. [...] Though there are approximately 1,000 Austronesian languages, the age of the family is thought to be comparable to that of Indo-European, and there is virtually no controversy over which languages do or do not belong to the family. The internal structure of the family is poorly understood."

Regarding to the Austronesian Expansion, Meritt Ruhlen (Ibid. 1994. p. 178) notes that

"The archaeological record of Southeast Asia indicates that the Neolithic revolution in this part of the world began in China around 8,000 years ago. Evidence of cultivation of millet in the Yellow River basin, and of rice, to the south, in the Yangzi basin, dates to about that time. By 5,000 B.P. [before present] farming had spread from this agricultural center southward to Vietnam, and Thailand and eastward to the coast of China. From this time period archeaologists uncovered villages with their accompanying pottery, stone and bone tools, boats and paddles, rice, and the bones of such domesticated animals as dogs, pigs, chicken, and cattle."

"About 6,000 years ago one or more of these agricultural groups crossed the Strait of Formosa (now the Taiwan Strait) and became the first inhibitants of Taiwan. And from Taiwan these ship building agriculturalists spread first southward to the Philippines and then eastward and westward throughout most of Oceania. The archaeological record indicates that the northern Philippines were reached by 5,000 B.P., and 500 years later these migrants had spread as far south as Java and Timor, as far west as Malaysia, and eastward to the southern coast of New Guinea. By around 3,200 B.P. the expansion had reached Madagascar, far to the west, and had spread as far east as Samoa, in the central Pacific, and the Mariana Islands and Guam, in Micronesia.[...]"

In the Epilogue Section of the same book, Merritt Ruhlen (ibid. 1994. pp. 195-196) re-emphasizes that the first two stages to start in order with the first step for the comparative method is classification, or taxonomy, which defines all language families at all levels. What is referred to in textbooks as the "Comparative Method" is really the second stage in the historical linguistics, for it takes the existence of a language family (the first stage) as a given and then proceeds to ask specific questions about that family. It is only then that the issues of reconstruction, sound correspondences, and homelands will be postulated with question such as "What historical processes were responsible for transforming the words in the proto-language into the forms we see in the modern languages, the daughters and the granddaughters of the proto-language?" Those questions can be satisfactorily approached only when the initial stage of historical linguistics — the identification of a language family — is complete.

The attempt to reverse these two levels on the part of the twentieth-century Indo-Europeanists and their followers, pretending that family-specific problems like reconstruction and sound correspondences must be used in identifying families, has led to current theoretical impasse in which everything but the obvious is considered beyond the limits of the comparative method.

That, nevertherless, is what the Austroasiatic therorists have done with the Mon-Khmer hypothesis of the Vietnamese languages.

That hypothesis of Vietnamese was first proposed by the Indo-Europeanists who used mainly comparative method to draw a number of basic words with similar meanings and regular sound change patterns within topological isoglosses to postulate their languages as being descended from common proto-languages. (I) Their methodology was based on mechanical paradigms such as methematical formulas drawn from Indo-European linguistic schools but its historical supports are seriously deficient, specifically of the people, their language, and their homeland, hence, they have failed to identify the language family first before getting into comparative analysis which is the second stage that they started with, reversing the order of the historical linguistic methology as Ruhlen pointed out as previously mentioned.

For all of the above, in this section the author will supplant the Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer hypothesis with history of Yue origin of Sinitic-Vietnamese (VS) under an anthropological view — in addition to the newly discovered basic cognates in Sino-Tibetan (ST) etymologies — of the whole language and its history only if Austroasiatic linguistic family is considered as that of the Yue people who originated from the habitat in the river basin of Yangtze or Yangzi (揚子江). If they could make use of them, consider them as freebies from the opposite Sino-Tibetan camp, something to complement each other from a different point of view to help find Sino-Tibetan etymologies of basic words in Vietnamese, currently many of them coming from the Mon-Khmer stocks having been taken for granted in their face value in the linguistic circle indiscriminately. Readers will see what the passage above means as they go on.

The term etymology used here is to mean the study of the origin of words or parts of their components, such as morphemes and syllables, and how they have evolved into the current forms. All the related words from different languages under investigation are called etymons or etyma. Specifically, it is related to those of Vietnamese and the Chinese counterparts, mostly about Sinitic-Vietnamese etyma of which scores of basic words could be traced back to those Sino-Tibetan etymologies. They are all results from the second stage as suggested by Ruhlen.

Before we get to the core of Sinitic-Vietnamese etymology, let us first position our stand starting from a geographical pivotal point much further in the north of where Vietnam is now located. Under the historical view, early ancestors of today's Vietnamese people who came from the present region of Phungnguyen Culture in Hoabinh Province, all had migrated there all from Dongtinghu Lake in Hunan (湖南) in China South (華南 Huánán), or 'Hoanam' of an earlier prehistoric period. Historically, the largest wave of southward emigration must have been that of their ancestral forefathers as refugees moving way from the invasion of 500,000 troops of Qin Shihuang (秦始皇 - 259 B.C.-210 B.C.) and during the period at war with the An Lushan Rebellion against the Tang's Minghuang (755-763 A.D.), the population of the empire had been reduced to a mere 16,900,000 from 52,919,309 heads recorded in the census taken before 755 in the mainland. (See Bo Yang. 1983-93. Zizhi Tongjian 資治通鍳, Volume 49.) Where were all 1/3 of the Tang people gone? They, as the refugees, fled en masse into Annam, resettled in the Red River Delta and mixed with the locals who were descendants of the earlier waves of Daic people from the southwest (Nguyễn Ngọc San. 1993. Ibid.) Scholars who study history of both Vietnam and China know it best that racial composition of ancient Vietnamese populace within such historical timeframe after the loss of the last NamViet Kingdom of the Yue people to the Han Empire, all being historical facts, is vital and relevant to the study of the Sinitic-Vietnam etymology. Languages spoken by the later immigrants from the China South made up the essence of ancient Vietnamese, or, to be exact, ancient Annamese.

A) New battles in the Sino-Tibetan front

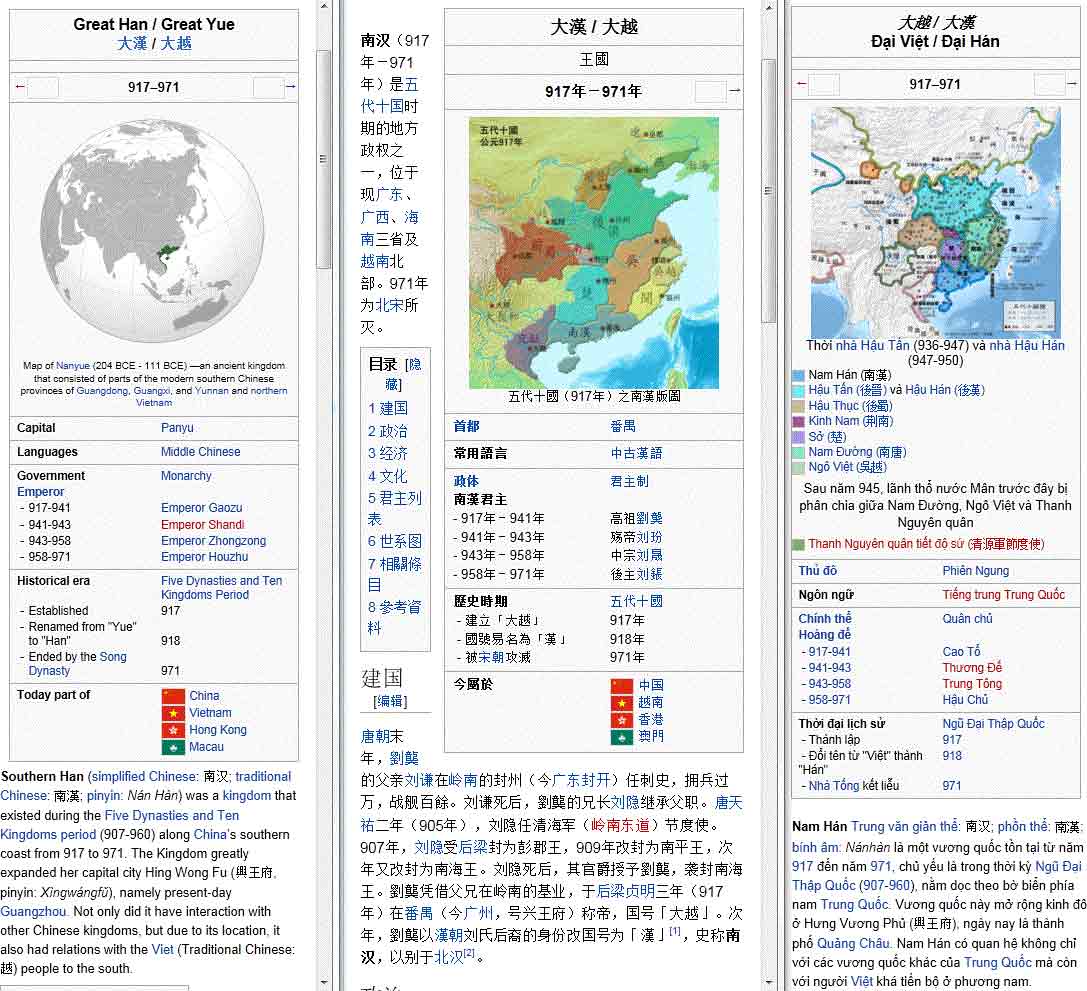

In search of the existence of the ancient Yue who lived there in ancient China, recent regional excavations by archaeologists have unveiled artifacts that match specific references to the Yue aboriginals called 百越 BăiYuè (BáchViệt) as recorded in Chinese throughout China's 5000-year-old history, of which ancient Chinese records confirmed that China South region was their native habitat of the ancient Taic people where where the Southern Yue (南越族 for 'NamViệttộc') and other tribal branches had originated from. (See Zhang Zengqi. 1990. 中國 西南 民族 考古 or Archaeology of Ethnic Minorities in China's Southwestern Regions)

Geographically aligned with 'China South' is what have been known as 'China North' 華北 Huáběi, or 'Hoabắc'. That is the heartland of the northern region of the Middle Plain, an area that stretches beyond the northern plank of the Yellow River from Shaanxi in the west reaching out all the way past the peninsula of Shandong Province (山東省) in the northeast to Bohai of East China Sea. The place was where many northern Tartaric dynasties throughout China's history were founded and ruled by foreign powers of Altaic origin such as Khitan Empire (契丹) or Liao State (遼國 916-1125) and it is there that the Early Mandarin of the Yuan Dynasty (元朝) was formed. From the latter dynasty of the 12th century, we have the Mongolian's Rhyme Book 蒙古 字韻 Menggu Zi Yun which shows how northern vernacular Mandarin to pronounce words then and Annamese Translated Wordbook 安南 譯語 Annam Dịchngữ which is a dictionary of the 12th centuried ancient Vietnamese vocabulary. A note to make here that a large quantity of northern words and peculiar idiomatic expressions, such as 'Sưtử Hàđông' 河東獅子 Hédōng Shīzǐ (tiger wife), found its way into the modern Vietnamese, and that it is not surprising to speculate that could probably be the result of the court's language as its vernacular form had been popularized throughout the Han colonial period in ancient Annam. So said, it is to explain the similarities between Vietnamese and Mandarin to counter rebukes by some scholars that Mandarin could not have influenced or have anything to do with the development of the Vietnamese language in such a late period, not to mention 25 years under the Chinese rule of imperial Ming Dynasty in the 15th century that all current Vietnamese literary works were destroyed and the whole nation had to use Chinese.

As far as the modern term "Việtnam" (越南) is concerned, it originally implicated the notion of "the Yue of the South". Meanwhile it implicitly suggested that there had also existed the "Việtbắc", or "the Yue of the North" (越北). Up until our contemporary era, those Sinicized Yue people, such as the Cantonese speakers (漢化粵族), have been living inside the borders of modern China but their ancestors might have not known exactly where their ancestral native habitat used to be in China South. That is to say, their ancestors had already scattered all over and the Yue tribesmen emigrated everywhere; they could already become the Yue of the North aforementioned. Interestingly, the same term, in a limited sense, also refers to 'the Yue of the North' (粵北) to those speakers of Mansheng 蠻聲 (#tiếngMôn=聲蠻!) of the Shaozhou Tuhua (韶州土話) subdialects beeing spoken in the border region of the north of Guangdong 廣東, Hunan 湖南, and Guangxi 廣西 provinces, which are mutually unintelligible with Hunanese, Cantonese, and Mandarin https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yuebei_Tuhua). Ethnologically, their forefathers were descendants of those earlier Taic aboriginals who had made up the population of the Chu State (楚國) as their Yue descents would have done to the Han Chinese population in a later period (See Bình Nguyên Lộc. 1972. Nguồngốc Mãlai của Dântộc Việtnam or "The Malay Origin of the Vietnamese"). Those ancient Northern Yue could be found living in the regions of today's China's areas where Hebei (河北), Anhui (安徽), Hubei (湖北), and Jiangsu (江蘇) provinces are now located.

Following trails of artifacts that their Yue descendants had left along their emigratory routes out of their ancient homeland of the Yangtze Basin as the early Tibetan nomads of prowess moved in approximately during the Xia Dynasty (夏朝, c. 2lst-17th century B.C.) or the Yin Dynasty 殷朝 (c. 16th-11th century B.C.), the proto-Yue tribes were forced to emigrate southward and they were past the Indo-Chinese peninsula — postulated the Austroasiatic (AA) homeland — and all the way to those faraway islands of Indonesia. The discovery of Đôngsơn-styled bronze drums reaffirms southward migration past the islands of Java and the New Guinea, which would logically to explain the presence of such cultural relics being found therein are similar to those of Dongson Culture (700 B.C.-100 A.D.) excavated in the Red River Delta in North Vietnam (See map.)

Bronze drums were produced by the Yue people from about 600 B.C. or earlier in China South and ancient Annam, or Han's Giaochi 交趾 Jiāozhǐ Prefecture, until the first century A.D. The 'Annal of the Later Han' (後漢書) recorded that the Han's General Ma Yuan (馬援) melt all the bronze drums seized from the local rebels of LuóYuè (雒越 LạcViệt) for bronzes (14 B.C. – 49 A.D.). The ones being found are those of the finest examples of metalworking by the indigenous Yue artisans.

The precise dating of those bronze artifacts for comparison provides some solid evidences to support the historical records regarding the ancient Yue people spreading to different regions. The earliest big and heavy Yue bronze drums similar to those found in Vietnam's Dongson were also found in Wangjiaba in Yunnan Chuxiong Yi Autonomous Prefecture (萬家埧 楚雄 彝族 自治州) China in 1976 that existed more than 2700 years ago. ( https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dong_Son_drums) Further work still needs to be done, though, to strengthen the archaeologically China South's Yue-based theory for the prehistoric period as opposed to that of Austroasiatic hypothesis of its Mon-Khmer linguistic sub-family, which makes the whole matter to look like both of them were of the same racial stock, but only in different timeframe settings.

We are here, however, not to talk about what happened 10 thousand or so years ago in China South and Southeast Asia's region, ethnologically and archaeologically. Such a timeframe is out of touch even with glottochronology which can probably postulate with some estimate of the genetic linguistic affiliation of daughter languages based on their 100 to 200 correctly-identified core basic words in active use within 5000 years or so (Roberts J. Jefers et al. Ibid. p. 133) This paper instead will focus on much of later historical periods that happened within a lesser timeframe approximately from 2000 to 3000 years B.P. surrounding the usage of fundamental words in some ancient aboriginal languages, their existence parrallel with one of the speech once spoken by the Chu (楚 Sở) population through the historical time that the Yue people were native inhabitants in China South prior to the birth of Middle Kingdom (中國 Zhongguo) as recorded in Chinese classic literature. ( See APPENDIX J: Yueren Ge (越人歌)).

Linguistically, Chinese-wise, all aboriginal languages spoken by the descendant-Taic populace of the Chu State (楚國) had blended with other Yue languages by the early Sino-Tibetan speech in the forms of proto-Chinese, Archaic Chinese (ArC-上古漢語) and other languages spoken by subjects of those ancient states to make up of the Old Chinese (OC - 上古先秦雅音) of which the diplomatic Yayu (雅語) were adapted by those states known to us, such as 吳 Wu, 越 Yue, 燕 Yan, 韓 Han, 趙 Zhao, 齊 Qi, 秦 Qin ... to have given rise to the Ancient Chinese (AC - 西漢古漢語) spoken by all later the Han-Chinese in the unified Middle Kingdom as known to the world as 'China' thereafter irrespective of all the dynastic changes). Nearly all Sinicized Yue languages spoken inside the China's border now become Chinese dialects, e.g., Cantonese, Fukienese, Shanghainese, etc.

Historically, on the becoming of the ancient Vietic language, in brief, as China's territorial expansion to the south continuously brought in the Han Chinese to Giaochỉ (交趾 Jiaozhi), or the ancient Annam was first called in Chinese annals, who strengthened more of their colonial rule by having put all indigenous Yue's customary way of tribal life all under the umbrella of the Han's institutions such as monarchal forms of government and Confucian education — a prolongation, anyway, of what all had been in place previously in the old NamViet Kingdom (南越國) that had been ruled by the Triệu Dynasty — and, for a good reason, sped up the process of Sinicization of the natives In Annam, the southwestern portion of NamViet Guo (Bo Yang, Sima Guang Zizhi Tongjian 資治通鑑, Vol. 2, 1983).

Anthropologically, primarily, populace with the racial admixture of the Han with the native Yue people living within the perimeter of today's China South all were enlised in the Han's army — as having been done since the previous Qin Dynasty — on the conquest mission invading the ancient Annam. The Han infantrymen had conquered the ancient Annamese land and stationed there. The early Han colonists resettled, then followed by civil officials and their families during occupying peace time under the benevolent rule by Viceroy Sĩ Nhiếp (士攝 Shì Shè), who spread the teachings of Chinese language and culture to the common mass and was very much revered by the newly arising Annamese aristocrats and later the so-called 'Kinh' plebeians. However, throughout the next 1009 years under the continuing harsh rule of Chinese colonialists, foot soldiers, refugees, officials, and Han immigrants, all continued to come, confiscate land, and resettle there, an on-going process still being seen till present. It was inevitably that social structure changes brought about the fusion of Ancient Chinese and languages spoken by different indigenous minority groups — Yue, Daic, Mon-Khmer, etc. — and that succeeding Sinitic linguistic layers evolved on top of the indigenous admixture substrata to have made up the early forms of the ancient Annamese language. Like their predecessors, the Han latecomers were intermarried with the locals and gave birth to the new masters of the aforesaid Kinh people in the habitat of ancient northern Vietnam at the expense of the native ones, such as the Muong and the Mon-Khmer groups who were driven or fled to the remote mountainous region and then became minorities in their own homeland.

All factors above were direct causes and effects on the becoming of the modern Vietnamese and their language in our time, the total Sinicized wholeness. To have full picture of it, imagine what would have become of a little vassal state like Vietnam, as compared to a small province of China, that had undergone its imperial colonialization 2200 years B.P.? That is exactly what will happen to today's Taiwan some 700 years later could possibly become (plus more than 300 years under the colonization by the Chinese rulers, i.e., descents of the Qing viceroys' followers stationed on the island, and the defeated Kuomingtang's armies who retreated thereupon, to make up the 1000 years-to-be Sinicization) but remember, with modern hi-tech comunication media in our era, there would be lesser changes in the Mandarin language as official use in the island nation as opposed to what had happened to ancient Annamese.

The history of the Vietnamese language appears to be straight forward from beginning as it has been first initiated by Vietnamese scholars that it evolved from the Sinitic branch of the Sino-Tibetan language family but the whole linguistic world seemed to enjoy initiating a new theory of some sort, one after another, and once in a short while. With regards to the origin of Vietnamese, after the initial Sino-Tibetan theory in the late 19th century that would be then followed by the Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer hypthesis. Institutionally, conspiracy or not, every specialist in a related field who happened to come up any discovery does so, such as the theoretical work by Paul Benedict (1975) who built anew the case of the Tai-Kadai linguistic branch with a newly established Austro-Thai linguistic family. Call it another "Austric" hypothesis for linguistic theories, i.e., just like that of the Gold Rush in academic fields, every linguist hurried to come up a new linguistic theory, of the century then.

That was not a simple process, though. As opposed the prehistoric approach by the Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer theory, the Vietnamese historical linguistics, to be specific, requires not only mastery of the Vietnamese language but also ancient Chinese philology — it was not as primitive as the first work by the pioneer Sinologist T.S. Bayer of the 18th century did (see Knud Lunbæk. T.S. Bayer (1694-1738), Pioneer Sinologist. 1986) — So said, it is because not every Vietnamese specialist, especially Western linguists, is able to distinguish Sinitic-Vietnamese from SIno-Vietnamese words in the Vietnamese vocabularies to identify Old Chinese remnants in modern Vietnamese, let alone Western learners of Vietnamese. That first appears to be a simple matter on the surface, but it is not, as admitted by most of Westerners who had tried to pick up the language.

In the early 19th century the Chinese historical linguistics was something new for Western scholars to venture. The learning curve on Chinese historical linguistics, however, seems to be steep enough for them to learn, but Vietnamese harder, especially its 8 tones in comparison with the 4-toned Mandarin. Ancient Chinese rhyme books such as Guangyun (廣韻) or Huiyun (會韻) that required the strenuously mental labor to make sense of syllabic extracts from radical and phonological values from ancient Chinese linguistics to decipher connotation that each Chinese character conveys and suggestive sounds in such classical Chinese books, for instance, the intrinsic radical as apposed to that the phonetic, or the intrigue "chongniu" (重紐) in divisions III, IV, etc. (音) in the study of Chinese historical phonology.

When getting their feet wet in the field Sinitic-Vietnamese counterparts, Western linguists would even encounter different standards once utilized by Chinese philologists in the ancient times that have already stirred up enough confusions for Sinologists because the methods of delivery in classic Chinese morphology were overloaded with Western "linguistic theorems" such as employment of modern methodologies which made the former look like 'unscientific' primers. However, by choosing to ignore the classic approaches, Indo-European specialists of, in our case, Austroasiatic have already missed important sound bits that had long been buried under hefty weight of classical Chinese dossiers. The core message hereof is that Western linguists will not make good research papers by picking the usual approaches like their predecessors, creating "breakthroughs" by inventing something new, as I will explain later on like in the case of exploring roots of an 'unknown African tribal A and B languages', of which the analogy is applicable to the theorization of 'Autroasiatic Mon-Khmer origin of Vietnamese'.

For the most parts, ancient Chinese classical and rhyme books have been underemployed, that is, not yet being fully appreciated and acknowledged as they ought to be. In so far as into the first half of the 20th century, only a handful of contemporary Western Sinologists such as Bernhard Kargren's Étude Sur la Phonologie Chinoise (1915) and Grammata Serica Recensa (1957), of Sweden's Stockkholm Oriental Institute, who probably the first one ever academically understood, explored, and made use of them in term of historical phonology. Though complete per modern measurements, his shift of focus to Chinese loanwords in Japanese, the author missed related Sino-Tibetan etyma that appear in the Vietnamese language. In any case, results of further studies like the overall of his academic work have benefited and contributeed great deal to the field of Chinese historical phonology meaningfully, including this Sinitic-Vietnamese survey that utilized his pioneer methodologies, specifically in reconstructing and resurrecting ancient Chinese sound values, which in the end will help in re-classifying the Vietnamese language into the Sino-Tibetan linguistic family (see Chapter Ten on the Sino-Tibetan etymologies.)

It is necessary to say it is partial to make judgment on native Vietnamese scholars doing research on the Vietnamese etymology of Chinese origin as well, especially for those approach the subject matter in scholastic aptitude, but time and time again, because of political reasons that are always raised highly with anti-China flags, their work veered off the academic impartial path to serve the political partisan line of the Commies. In order to be excused from executing the Sinitic subject matters in Vietnamese indiscriminately, they are disinclined with real issues of Chinese linguistic affiliation by sublimating into the alternate realm of nationalism, and they have found the safe haven in the Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer realm. The end justifies the means, as the saying goes. That is, to be safe, many of them have chosen a stand distant from Chinese affiliation by avoiding the whole political matter altogether. It appears, though, such runabout shortcuts would not make it in Vietnamese etymological studies as the reader will see they are so entangled with Chinese and Sino-Tibetan etymologies. We will deal with this messy politics in a separate chapter in detail to understand mentality held dearly by Vietnamese linguists, which is rampant and has seriously interfered with expected objectivity in academic neutrality.

Of the so-called 'the Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer rainwash' as mentioned previously, hence a convenient excuse, the degrading term has been stemmed from the account that lately contemporary Vietnamese scholars — unlike those scholars in South Viertnam pre-1975 period such as Lê Ngọc Trụ, Nguyễn Đình Hoà, Nguyễn Hiến Lê, Hồ Hữu Tường, etc. — have taken side with the initiators of the hypothesis of Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer origin of the Vietnamese language, and they altogether just disregarded anything Chinese one way or another. As it appears presently, plus given the fact that the West had poor knowledge of Chinese until the 19th century (see Knud Lumbæk. 1986), we have the right to suspect that Austroasiatic pioneers from the bygone era of the previous century, however strong their innovative initiative could be, all seemed to have conspired with one another in a scheme to start with Austroasiatic premise. They seemingly made what they did rather easily without the burden to exert too much effort on their part, such as to investigate the history of respective country that has its language under discussion and to learn related Chinese dialects and subdialects in the field.

The early 20th-centuried historical linguistics saw the grouping the Vietnamese language into the Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer linguistic family based on comparative data from the tabulation of scores of basic words among many Mon-Khmer languages cognate to those of Vietnamese that scatter sporadically. However, only a tiny portion of their selective loanwords fall into the range of 99 percent of Vietnamese vocabularies, though. They raised the stake as they fell into the realm of what is considered as core basic words. After they were done with analysis and postulation job, our Austroasiatic fellows went on blanketing identified Sinitic-Vietnamese fundamental items paired with the rest of Sino-Tibetan lexicons as Chinese loanwords. Of course, they did not bother or intentionally avoided offering an explanation for all other linguistic peculiarities of the Vietnamese language that share with the Chinese language, which never, ever exists in Mon-Khmer languages. In their era, many of the Indo-European theorists — those who initiated the Austroasiastic theory — might have never heard of the "Yue". For example, not until lately, they had been unable to distinguish which one is from Yue, which one from Chinese, e.g, 戌 xū, 狗 gǒu, 犬 quán, etc., that is cognate to Viet. 'chó' (dog) for which they are all assigned */kro/ because it is easy to recognize it as of the Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer sub-family. "

Only after all these years, a few of Austroasiatic specialists have started to take notice and made use of well-prepared works on Chinese and Vietnamese by others as a baseline to have stepped up the process of theorizing their Austroasiatic hypothesis (A), including those notable papers by Tsu-lin Mei (1976), Jerry Norman (1988), Mark J. Alves (2001, 07, 09), to say the least. Howevever, surprisingly, certain of them failed miserably to distinguish Sino-Vietnamese from that of Sinitic-Vietnamese class in Vietnamese vocabularies as they appeared in their citations. Sino-Vietnamese vacabularies in Vietnamese are analogous to those Latin words in English, plain and simple, but the matter was mixed up in the process. In addition, they have never stepped out of the constraints of common norms on traditional approaches and techniques, for example, repetition of citing those basic words of Mon-Khmer cognates over the last five decades since David D. Thomas (1966), that is, no novel breakthroughs in nature about them to counter evidences that show the Sino-Tibetan or Chinese origin of those related words being cited.

Work of reinforcement on the Mon-Khmer theory built on the Austroasiatic foundation, as a result, have proliferated on the internet especially in the last two decades. The Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer theorists, hence, had undoubtedly gained an upper hand in competing for the total embracement of their theorization in addition to other technical gains after long decades of having continuously cultivating the belief that Western methodology is scientific and superior, implying assurance of the same quality for their newly built the Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer theories. The brand-nameed Western institutions associated with their work have effectively attracted many local followers inside Vietnam who eagerly showed their admiration for those Westerners that demonstrated some knowledge of Vietnamese. Following the crowd with the trendy fads puts up some vanity air in their own locally made products, as a result, but of disputable academic values. Such partial outcomes from their research definitely would hinder the progress of our overall efforts in trying to rekindle interests and recognition on a renewal of work attempting to reclassify the Vietnamese language into the Sino-Tibetan linguistic family.

As the time goes by, continuing recognition of the dominant Austroasiatic theorization has further consolidated the legitimacy of its Mon-Khmer hypothesis on the Vietnamese origin as being uncontested for a long period by now. The whole matter in turn has posed an unfavorable environment that forced Sino-Tibetan theorists to go underdogs because their camp could not come up with something new and plausible on the whole matter until this survey on Sino-Tibetan etymologies (see Chapter Ten.) Meanwhile, the sentiment has turned ugly into political rows under the disguse of nationalism and that would implicate even more on the issue of one's own national identity because, collectively, the people of a nation will realize they are not what they have been told all along.

The Vietnamese know best that history of their country has been rewritten anew as dictated by rulers of the country to reflect changing viewpoints on Sino-Vietnamese relations; hence, theories on the origin of their people have also changed accordingly regardless of the truth. In other word, the winner writes history. On the opposite side of the scale that balances the overshadowing China and academic truthfulness in our contemporary era, the Vietnamese historical linguistics is apparently weighed with more of a political issue like that of history, i.e., writenn by the winning side. The phenomenon just reflects a pattern of what their predecessors did in the past, i.e., waging resistance wars against the imperialist China. Ironically, the core matter still remains so Sinicized in many aspects of Vietnamese culture. With regard to the philosophical aspect of the historical linguistics, for the average educated Vietnamese persons, national awareness of identity has blurred the Sinocentric Sino-Tibetan line even though it still trails far behind the Chinese. In any cases, they wholeheartedly welcome the late Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer entry, of which its groundwork has been elevated gradually over time and gained more local support.

While the matter created a convenient excuse to accept novelty of the Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer hypothesis, the Vietnamese academics figured out a way to walk around the Sino-Tibetan shadow, The issue, nevertheless, has outgrown its outfit into some sizable magnitude for any individual scholars to handle on their own. Working with an anti-Chinese attitude went counter natural development in a scholarly field, which is anti-academic to the extreme, getting our native Vietnamese scholars to nowhere. Nevertheless the so-called national sentimentalism held by the Vietnamese would not go away any time soon by just denying the old Chinese affiliation and establish the new one. Truthfulness always exists as an influential force in the backstage; therefore, the time will come for resurrection of old belief that will bring all the nationalist warriors back to their sense out of the anti-China mainstream, learning how to separate academics from politics so as to roll back the long-lost conviction. Renewal of such respective belief infers to not only the field of Vietnamese historical linguistics but also natural scientific fields as well, such as biogenetics used to identify the racial origin of a country's population by tagging the genome map of targeted people.

As a matter of fact, it is difficult to ignore politics indiscrimately to differentiate a country , its people and culture from its ruling government. It is rolling back of the past projected into the future is possible. Before Trump's presidency we had seen more and more new so-called Confucius institutes — Chinese cultural centers fully subsidized by the Chinese government on a large scale for their own hidden agenda as one could easily guess — have popped up in larger numbers and they already impacted US institutions through donations and parts of their efforts are to spread China's influence around the globe. In effect, it is the new Chinese learners who will shift the balance on their side as more of Chinese savvy, not the aging Austroasiatic, as the Chinese language increasingly attract more younger students outside of China. In the end Vietnamese theorists will incline to the Sino-Tibetan theorization then. It is then the axiom that people tend to believe in what they have already believed in still hold fast. Let us wait and see how such new trend will come regardless of its negative impact. As a result, the whole new shift in attitude is expected accordingly with respects to linguistic matters that will soon change the Sino-Tibetan landscape that we are focusing on in the survey. We can say that historical linguistics changes as it did in the past, like any other humanities.

Readers may ask how on earth academic matters have anything to do with nationalism? Firstly, the answer is the national identity has sublimated into nationalism. Talking of historical linguistics, the Yue core of the Vietnamese basic words were donned under the Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer attire to avoid implicating Sino-Tibetan or any Sino-centric termimology because that is certainly related to Chinese, so to speak euphemistically of politics. For Western-educated persons of non-native Vietnamese would probably find it hard to grasp the implication of how Vietnamese politics got entangled so deeply with any Chinese-related academic subjects in the first place, and subsequently there is no exception for Vietnamese historical linguistics. No one understands that better than those locally groomed Vietnam's scholars, including her diasporas in exile in our modern time. The delicate Sino-Vietnamese relations are to be dealt with later separately to show that the truth of the matter could be either twisted to serve solely a political purpose that can be disguised behind a mask called nationalism.

Be reminded that history of Vietnam is chronicles of continual resistance wars. Wind of war against an imminent Chinese invasion is always on the threshold in Vietnam's northern border at all times. The total years in Vietnam's history being at war are greater than what they have had for peace. Of the 2,273 years of her written history — not orally from legends or folklores — recorded from Thục Dynasty (257 B.C.–179 B.C.) Vietnam had gone to wars for 1,474 years having fought against the Chinese aggressions sporadically with the last war that only ended in 1979's border war. That is in in paper, though, because Chinese forces' intermittent incursions on land and at seas have become more of a routine, which gradually culmimated in major clashes in 1984, 2013, 2015, etc., not to mention 262 years in total at intervals plunged into factional civil wars and fought with the Chams, Khmer, Siamese, French, Japanese, including South Vietnamese army against the USSR- and China-backed North Vietnamese forces and, vice versa, the North Vietnamese against the US troops involved, all more or less involving interventions by, again, China on either side. All in all Vietnam had a mere 898 years of peace time by piecemeal, to be exact.

Undoubtedly, the war-hardened perseverance has molded strong will for survival and that has made up what the Vietnamese perceived as nationalism, something that is real and concrete as exemplified by past events taking placed in the early 10s of the 21st century where young patriots staged demonstrations against China. In doing so they even accepted jail time handed down by, ironically, their own government in their own country for the crimes of raising their voice against China's aggressions. Several of them have been sent in exile as their nationalism shines. Resentful sentiment towards the sole northern neighbor has continued on and passed down to the next generation at all times. So it is of no surprise that nationalistic view becomes a degrading factor in establishing academic objectivity — again, not a product of imagination — in theorizing the core Vietnamese linguistic affiliation matter, either the Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer or Sino-Tibetan camp. Earlier in the previous sections and in a separate article-length paper, the author already argued that the Vietnamese people are of mixed race, firstly, as a result of racial fusion of Chinese immigrants from the north who resettled down and married local women. Therefore, it was fair enough to see how intellectual and patriotic netizens got enraged with fierce reactions (to follow the issue, google with my penname "dchph" or see Some Thoughts on the Origin of the Vietnamese People in Vietnamese or in the APPENDICES section of this survey.) In this paper such uneasy racial profiling will be used to support the point that from 111 B.C. to 939 A.D. as the ancient Annam was a prefecture of the imperial China, like any provinces or prefecture within the Middle Kingdom, Chinese immigrants with different dialects kept coming in and, eventually, their linguistic fusion with those aboriginal speeches evolved and buried the Yue linguistic stratum out of sight deep down on the bottom layer. The whole chained events as such have given rise to the modern Vietnamese of which over 90 percent of linguistic elements are composed of Chinese linguistic components.

Thanks to political issues, the reader will see why the author has set aside a whole chapter solely to discuss influence of Sino-Vietnamese politics, which has pressed on academic arena because it matters so much in forging impartial judgment on whether or not the Sino-Tibetan theory would hold fast and flourish in its new stand. Those who know Vietnam's history published by the ruling government might appreciate a little the antithesis of the matter, so to speak. One virtually could not bring Western value standards to understand them.

To easily grasp the core issue of the matter, let us again compare similar circumstances, this time with the three nations in the region that accepted largely a great number of immigrants from China into their population, just like what Vietnam has done thoughout her history, that is,

(1) Singapore, having enjoyed its status of sovereignty since 1965, is a country of multi-ethnic citizens with a Chinese majority;

(2) Hong Kong is now going through successions of its darkest days as of 2019 with most Cantonese speakers coming from the mainland of China of which the status of the colony passed down from Britain to China is like what the historical ancient Vietnam having started with since 111 B.C.;

(3) Taiwan with its de facto independence has always been in an uneasy co-existence with the mainland China, having its sovereign status similar to that of Vietnam, seemingly to be shaken at intervals past and present.

Of all of the above, analogously, the Tainwanese are also experiencing an identity crisis in weighing choices either they should take side with Sinicized Minnan (閩南) values brought over by their forefathers from the ancient MinYue Kingdom (閩越王國), now of Fujian Province, to the Formosa island since the 16th century or they would better relate themselves more with the Austronesian natives, who are still chewing betel nuts, to stand up as genuine masters of the island joinning in the fight for the Republic of Taiwan instead of Republic of China. On the side note, the native mimorities living in those places were at first not in equal footing with the massive Chinese mainlanders who followed the Kuomingtang troops seeking refuge in 1949. For what is considered as analogous to the last case, the Vietnamese people are only concerned the question whether they were descended from the majority of immmigrants from China South or minority of indigenous people, but their nationalism has transformed into national politics, so to speak.

On the other side of the coin, for the most parts history of the Middle Kingdom was full episodes of being conquered and ruled by other foreign elements from the north of China North (華北 Huabei) such as those of Tartaric, Altaic, Mongolian, and Manchurian rulers who each in succession had gained the control of the Middle Kingdom being known to the world as China and their subjects later made up the people collectively called 'Chinese'. That is to say, 'Chinese' consisted not only the southerners but also those of the north. For those who joined the colonial army to have gone south and conquered the Annamese land, they all mixed with the local people to have evolved into the 'Kinh' people.

For those Chinese refugees who later emigrated to Vietnam such as the Ming expatriates (明鄉人 'NgườiMinhhương') after the Manchurians brought down the Ming Dynasty, their last rounds of resettlement would make up another different racial component of the larger contemporary Hoa ethnicity (華橋) in Vietnam. Many of them were of Tchiewchow origin from Chaozhou region in Guangdong Province such as Foshan City (佛山市), their population made up a larger portion of the 'Kinh' people in six southernmost provinces of Vietnam today, as an old saying about the southwestern land goes, "Dướisông cáchốt, trênbờ Tiềuchâu" that means "in the river there are catfish, on land there are only Tchiewchow people."

To make the matter to become more complex, in contrast to the Yue minority status as in China South, subjects of the Southern State — or 南國 Namquốc (nướcNam), as Vietnam called herself casually — are having obsessed with their pride of the Yue ancestral heritage as manifested in many ancestral sacrificial ceremonies performed annually. Ironically, the Vietnamese Kinh majority do not hide their haughty overbearing over minority people, who were supposedly the true masters of the land where the Vietnam's nationals are now residing on and they all might have descended from the same ancestors as well. Anthropologically, the early Yue natives of the ancient NamViet Kingdom (南越王國) had long met with similar racial discrimination under the rule of succeeding imperial Chinese dynasties since 111 B.C. and emigrated out of the China's mainland pouring into its Annam Prefecture. History witnessed their having becoming the new masters of what belongs to the eastern part of North Vietnam today (Bo Yang, Ibid., Vol. 69, p. 172. 1992).

Ethnologically, we could say that Vietnam is the only sovereignty still in existence that could be considered as a representive state of all of Yue descents and their cousins such as the Daic and Zhuang minorities who are still living in China South and their populace are so populous and strong the Chinese goverment granted autonomous status for those regions. Note that for the latter many of their ancestors fled to remote mountainous terrains across many southern provinces of China when their territories fell to the hands of the Qin's invaders. Current China's ethnic groups were descended from the common ancestral Yue people who made up the ancient Chu and Han subjects prior to 111 B.C. and thereafter. Of the Han's era, parts of the Han population were composed of the Sinicized Yue people having been descended from subjects in those annexed "ancient states". The "original Yue-Chu-Han Chinese" (C) later made up the troops that advanced to the south and conquered Giaochì (交趾), or the ancient Annam. Comparatively, in Annam, until its independence in 939 A.D., exclusive of those Han immigrants to the Annamese land throughout the 1060-year colonial period, racial components of the whole population would have remained virtually the same balance of the populace in the ancient Lingnan region (嶺南道) that consisted of today's provinces of Guangxi, Hunan, Guangdong, Fujian, etc.

As Vietnam's national identity resurrected after her separation from the imperial China, her nationalism have grown stronger out of several resistance wars against Chinese invaders of every dynasty that was suceedingly established in the land of Middle Kingdom, namely, the Song, the Yuan, the Ming, the Qing dynasties, and their successors who now rule the PRC (People's Republic of China). Everytime when each Chinese monarchy had reached the height of its power, each succeeding monarch never ceased trying to retake Vietnam, at least aiming to subdue her into a position of a vassal state. Is today's China militarily stronger than the Empire of Mongolia was in the 12th century on a comparative level? Beyond any wildest European imagination, the Annamese defeated the Mongols not once, but thrice. It is too bad that all of the emperors of China, past and present, have never learned the lessons of Vietnam's history. It is no matter how powerful each dynasty had become, though, each one was eventfully defeated by Vietnam, including the border war as recently as in 1979.

Of the same matter, for the most part of the Vietnam's history, sadly, the Vietnamese men were born just to go to fight in wars one after another and the last one just ended her 10-year war against the China-backed genocidal Khmer Rouge in Kampuchea in 1989. Thanks to constant invasion threats from her northern archenemy, Vietnam has been constantly in preparation for the next war with China as always. In a sense, no other nation on earth could ever get so high on spirit regarding nationalism that got stronger over time. Each of the Vietnamese segments, from the ruling parties to scholars to the common mass, all has their way to deal with nationalistic issues.

In the national arena, the ruling members of the current Poliburo altogether have made the whole people in Vietnam to pay dearly for their war debts owed to the communist China that had helped put them in power in return for their fighting along side with China to serve its expansionism of neo-feudalism, i.e., communism, in the Vietnam War against the US-supported South Vietnam's government (1954-1975). The rise of the Maoist feudal state again denied Vietnam a fair chance of peaceful restoration of national independence from the French colonialists (1858-1954) and free of tyrannical rules thereafter, politically, as being enjoyed by many countries in the region such as India, Malaysia, or Singapore after the domino-affected collapse of Western colonial rules in Asia right after the WW II of which some lasted until the early 1960's. There is no need to say, economically, the costs of war of having fought one after another for over the last 300 years have been emormous that have held the country at the bottom of an abyss with the meager chance for keeping abreast with the times on any progress in churning out any valuable research. The point to make here is that readers should not rely on the current respective government's academic institutions for highly-acclaimed for any scholarly work because those work in the field are simply the organs that serve the regime. (See Knud Lundbæk. 1986. p. 45)

Explicably, the local scholars tend to deny themselves of links to the past that had anything to do with the Chinese, e.g., share of 1000-year-plus history prior to 939 A.D., so they choose to go with the Western trend —note the naivety of Western scholars who have been hoorayed to the skies when being able to utter some Vietnamese words —in accepting the Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer hypothesis that is likely that of the Yue. It is believed that nationalism inflamed by the national forefathers is still being funneled inside the hearts of the younger generation, though. Even though for the learned Vietnamese youngsters, the Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer theory of genetic affiliation is just an academic classification, when facing sensational issues about their ancestral origin, like the American youth in the USA who might lose traces of the ancestry originally, they do practice self-denial of true identity, mostly of Chinese descent based on their genetic line of paternal family's tree approximately three or many more generations ago, by accepting as a member of the "Kinh" majority which is a general ethnic-designated category implicating only ancient Vietnamese values, namely, those of the Yue genealogy. When the next generation takes over their current spot, they will share the same feeling by those of the older ones, who did the same in their time.

The selective choice of the Vietnamese intelligentsia shows that in their collective consciousness they are well aware that their ancestors have migrated from the region north of their country's border, or to be exact, the China South homeland. In other word, historical matters of the later acquired southern stretches of land, though having the Austric roots as proposed in the respective Austroasiatic and Austronesia theories, did belong to other different peoples, forefathers of the ancient kingdoms of Champa and Khmer that had nothing to do with the ancient Annamese.

Symbolistically formularized, if we are to express all Yue entities in formulary terms to represent the proportion of racial transmutation which brings the genetic affiliation for the ancient Annamese inside a formula, we shall then assign some numeric values of weight to their racial entity with componental properties as {2Y3Z4H}, loosely formulated based on historical records such as census data of population increasing more than double from 400,000 to 980,000 people in three Han's prefectures of Jiaozhi 交趾 (Giaochỉ), Jiuzhen 九真 (Cửuchân), and Rinan 日南 (Nhậtnam), respectively, throughout the 100-year period from 111 B.C. to 11 B.C. Historical records, furthermore, show that NamViet's 15,000 to 30,000 unmarried women were forced to marry Qin foot soldiers during the short-lived Qin Dynasty (Lu Shih-Peng, 1964, Eng. p. 11, Chin. p. 47). How the post-Qin-Han Chinese further blended with the Yue, and the fusion of both racial entities gave rise to the present Vietnamese — after the elongening process of more than 2000 years that in turn have been results of racial fusion of the pre-existing natives in each locality where the Annamese resettled. For the principal purport of the following enumeration of the Vietnamese racial mixed components, they are not pretended to be scientific, but to incite your imagination on the becoming of the ancient Vietnamese.(S)

The composition of the Vietnamese racial admixture appeared much more similar to those racial components that had made Han-Chinese. In general, the whole process had been a result of evolutionary progress during which the early proto-Chinese {X}, of Tibetan origin from the southwest of the mainland of China, intermingled with the proto-Yue aboriginals {YY} (assumedly the Taic people, the main populace of the Chu 楚 State who once, assumedly, spoke an ancient Daic language) — on the proportional ratio of 2 to 1, that is, 2Y/X — to have become parts of the ancient Yue indigenous populace represented by {ZZZ} in those ancient states of Shu 蜀, Wu 吳, Yue 越, etc., of which their mixed subjects were later called 'the Han' symbolized as {HHHH} — that is, 3 x Z, 4 x H, repectively, where "x" means "times" — in a unified Middle Kingdom under ther rule of the Han Dynasty, sort of a "united states of Qin", for what the Qin people were later known as 'Chinese', analogously, and then when changing hands into the Han, they were called as the Han people.

Composition of the later Han-Chinese as {X2Y3Z4H}, in effect, were results of mutated racial fusion of {(X)(YY)(ZZZ)(HHHH)}, so to speak, while racial composition of the Viets — nationals of Vietnam throughout different historical periods — was made of the proto-Yue {YY} and later Yue {ZZZ} to become the proto-Vietic {YYZZZ}, ancestors of the Vietic (Annamite), or the early Annamese {2Y3Z4H}, who later evolved into the modern Vietnamese {4Y6Z8H+CMK} where {C} is for the Cham and {MK} for the Mon-Khmer, a componental double (2x) of {2Y3Z4H} plus {CMK} taking place with a series of similar events that had brought about the same composition of the Fukienese or Cantonese, of which the populace had the same racial transmutation as that of the Vietic admixture during the same period under the rule of the Han Dynasty before and after 111 B.C. So it was, suggestively, only then the symbolistic formula for Austroasiatic could be assigned as {6YCMK} as apposted to the modern Vietnamese {4Y6Z8H+CMK}. (See Time maps of China

Source: http://www.timemaps.com/history/china-1500bc

Linguistically, the process of linguistic sound changes took over and accelerated, including morphological and lexical changes, from one subdialect to another. Modern Vietnamese subdialects demonstrate how the sound changes vary lightly from north to south probably since Annam became a sovereignty. Currently, as the Viets continued on their journey further to the south, they brought with them their language to their new settlement from the time they lost contacts with Tang colloquial variants — as opposed to Cantonese — since 938 when the colonists of NanHan Empire (南漢 帝國) were defeated by Annam's General Ngô Quyền (吳權 Wu Quan as named in Chinese history) who became the first head of state of the independent Annam in the following year (Bo Yang, Zizhi Tongjian, Vol. 69, 1992. pp. 209, 210). For vernacular changes in the Vietnamese language, all migratory movements from the north to the south have left tonal marks on a continuum which shows gradual stages from those of full 4 two-register tones of Hanoi to 4 single-register tones, that is, Hanoi ~> Nghean~> Hatinh~> Quangbinh~> Quangtri~> Hue become those heavily-accented subdialects spoken in Danang ~> Quangngai~> Binhdinh~> Tuyhoa~> Ninhhoa~> Phanthiet, all gradually turning into laxly-lighter 6 tones of Saigon~> Lụctỉnh (6 southernmost provinces), namely, the free-styled southwestern accent in the Mekong Delta. No matter how one substantiates subdialectal dissimilarities, any of them is intelligible by most Vietnamese speakers. If someone has a difficulty in understanding one subdialect from the other, it is only regional vocabularies to blame. For example, lexically, the semantic difference may lie in the fact that speakers of the northern Vietnamese subdialect tend to use sophisticated Sino-Vietnamese jargons than the relaxing mode of speech used by most Vietnamese linging in the southern parts of the country even though the latter being the last subdialect that has started forming merely some 350 years ago.

The perception that their national language was on par with any Chinese dialects and once considered as a sub-family of Sino-Tibetan family language might have not been easily disturbed until the last century when Austroasiatic hypothesis sought to cover all languages in the Southeast Asia under its umbrella and Vietnamese was one among them under the new Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer classification. The Austroasiatic camp did not take into account of the historical factor that the massive immigrants from the north had overrun the indigenous people after they resettled in the ancient Annamese land for at least two millenia hitherto. Hypothetically the French — instead of the Mon-Khmer — had come to colonize Annam and would have overstayed the local hospitality by the same length of time, there would be no surprise if the colonists picked up some indigenous basic words and incorporated them into their langue Française-Annamite. In a imilar fashion, that was how the ancient Annamese had accommodated Mon-Khmer linguistic substratra which caused them show on the Austroasiatic radar screen.

In the prelude to the coming of French colonialists into the country in the mid-19th century, European missionaries had arrived and stationed inside the country as mouthpieces of propaganda of the Catholic Church since the 17th century. Representatives of the Church had full support from the colonial government to spread Western values aggressively in form of passing Gospel to the illiterate mass and literati alike. After Annam fell under the French colonial umbrella in 1862 that lasted until 1954, Annam under the rule of the French colonialists was fully prepared to enter the new phase breaking away from haunting past with the China with the adoption of the Romanized orthography for the Vietnamese writing system and complete abandonment of the use of thousand-year old Chinese-character script. It was not long after the local nouveau literati were put in contact with French academics, the whole perspective shifted in favor of the Western academics. Since the 21st century Vietnamese scholars are mostly in opposite belief with what of the 19th and earlier ones.

As a series of historical events reeling thereafter — such as 'divide to rule' policy that of the division of Annam into 3 different administrative dominions, or colonized administrative regions, i.e., the Tonkin, Annam, and Cochinchina, respectively, by the French colonial government for the next 92 years — did serve as the end of the monarchy of the Nguyen Dynasty from the Imperial Hue Capital City in the Central region that their monarchal system still in place was only acting puppetry that showed the Vietnamese people the backwardness of their country for following the feudalist system of China. There occurred the most fierce attacks from the West launched against the two most backward and corrupt but resiliently repulsive citadels of Confucianism by then, that is, assaults by the French force attacking the Annam's Hue Imperial Palace in 1883 and later by the Eight-Nation Alliance troops that swept the Qing's monarch feet off out of Peking's Forbidden City in 1900, respectively, both having been unmercifully ransacked one after another, of which their booty are still in display in many larger museums in the West. Only through the light of Western Civilization shining in the southern region — overshadowed by the colonial oppressiveness, yet, with innovative minds of those Frenchmen that stood for the fortifications of Western Civilization, though — were the occidental ideas that posed cultural threats to those who hold on to the traditional values. The Annamese were able to rise up on their feet and to see beyond China's horizon

Successive historical events continued to unfold thereafter helped France move Annam away from Chinese umbrella, which signaled the collapse of the old monarchy systems in both China (1911) and Annam (1954). Western Austroasiatic theorists stepped into the threshold to fill in the linguistic void that the incomplete Sino-Tibetan hypothesis was left vacant behind that was still want of substantial proof to prop it up into a plausible theory and they captivated the Western-educated Vietnamese scholars of the second half of the 20th century, which allowed them to perceive their own national language via its Western periscope in place of the old Chinese scholarship hold dearly by the previous generations that ought to have expired by then.

In the process of colonialization of the highly Sinicized Annam's society, those overly enthusiastic colonialists, wasting no time, sprinted into action to propagate their Western values with multiple cultural prongs that include imposition of supposedly superior occidental values to those of the old Chinese ones; one of their purposes had been to secure their footing there through the supporting colonial French government. Academically, Western methodology was prominently one among them and proved its quasi effectiveness in most of academic fields. Throughout the colonial period, however, French intellectuals were always in a position of authority to forge Western scholarship that envied the old Confucius values they were anxious to replace to the point the their jeaousy had gone too far. For example, a French-educated Vietnamese of the mid-20th century generation might recall that when the French colonists were there in Annam, they had even gone far enough in the field of history by boldly teaching — of course, in French — their colonized Annamese native school-aged children that their ancestors had been of the Gallic race, and ironically, many French colonialists were not even are that they themselves had never spoken their ancestral Gallic language, but latin-based French.

Then came the last century that witnessed how efficient Western mechanism had been at work through showdowns of forces between those new vanguards of the Western values represented by the US throughout the Vietnam War against the same old tyrannical system of the neo-feudalist China being dressed under a new attire of 'communist monarchy' ruled by the Party's Pulitburo headed by the genral secretary who also serves as the country's president, from 1945's President Hồ or 1949's Chairman Mao to the present 2019's presidents Trọng and Xi in each respective China and Vietnam. Historically, from 1964 China had already started funneling arms to their power-thristy Vietnamese communist comrades who helped the China's expansionism in the ferocious showdowns of Chinese communist and democratic Western forces in South Vietnam during the US-USSR detente Cold War period. After China-backed North Vietnam finally won the war in April 1975, the Viet-commies built their totalitarian regime that tolerates neither criticism nor freedom of speech, which has led to the distortion of academic truth aforesaid.

On the one hand, it is undeniable that the Western ideas make physical transformation in real world. At every corner the Westerners have gone, they bring modern progress with Occidental values there with them to. Novel scientific methodology proved their superiority through effectiveness and advancement in many aspects of civil society. Ironically, the world has seen nothing yet in terms of utilization of hi-tech in civil surveyance that has grown with China's economic powerhouse that can take control people from eardropping smart phones to obstructing boarding trains or buying cars, all done with Chinese technological copycats with the same efficiency, an stunning development only after a little more than 30 years of economic reform policy in implementation of what the Chinese have learned from the West. In actuality, if China had become a free of communist centrally-controlled policing state, it would have advanced at a much faster pace by now. But here they go with all the censorship and blockade of all information outside there networks, from Yahoo to Google emails to Youtube, and Twtitters, etc. all being kept at bay outside the new Great Fire Wall. It feeds an army division of social media troops to guard and entice people into double-speaking traps.

On the other hand, the Vietnamese intellectuals are taking notes on personal rewarding incentives, e.g., recognition from the academic world, that go with proven benefits based on can't-go-wrong Western methodologies, in this case, the Western-initiated Austroasiatic theory, specifically. Despite controversiality on association of the Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer with Viets, local academics are eager to take on the prestigious Western stand of the Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer hypothesis because it is easier to reconcile it theorization with archaeological excavations — for example, focus on the southeastern region of the Indo-Chinese peninsula as homeland of the Austroasiatic roots in order to explain finds of highly advanced Dongson-styled bronze drums found in both China South and Indonesia (see Paul Sidwell's The Austroasiatic Central Riverine — than elaborate on non-factual traditional Vietnamese legends, folktales, and folklores, etc., to depict one's national prehistory that all sounds more like fairytales. Such oral forms certainly earn negative marks and pose challenges on its credibility for interpretation of prehistoric events even though that is how one generation to another passed down tales of the founders of the nation long before they were recorded in Chinese history since their contact with the 'Tàu' (秦 Qin) people prior to 204 B.C.

Nobody might ever suspect that the state name of ancient Vietnam "Vănlang" as recorded first in Chinese Annals as 文郎 Wénláng would have anything to do with "Penang" — like the name of the island State of Malaysia's 'Pulau Pinang' (Viet. 'Cùlao Cau') which means 'The Island of the Areca Nut Palm (Areca catechu)' or 檳榔嶼 Bīnláng Yù — may be related to the actual Chinese transliteration of 檳榔 Bīnláng ( SV 'Tânlang' <~ */blau/ } or "trầu" (betels) in modern Vietnamese!

Read more at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Penang

However, the Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer camp could never be able to compile basic words across all Mon-Khmer languages to find certain cognates to match what exists in Vietnamese that could relate to Vietnamese legends to help identify sound change patterns as reliable as the Sinitic-Vietnamese etyma in Chinese records. For example, 董 dǒng in the legend of "Phùđổng Thiênvương" (扶董天王 Fúdǒng Tiānwáng — a mythical folk hero in Vietnam's history, who defeated the Ân (殷 Yin or 殷商 Yinshang) invaders from ancient China's Yin Dynasty, (Y) ) — is also called 董聖 Dǒng Shèng (Đổng Thánh) or normalized 'Thánh Gióng (Dóng)', that is, Saint 'Dóng' or 'Gióng' /Jong5/ and the phonology of both pronunciations are mapped well into the sound change pattern of { /t-/ ~ /j-/ } and { đ- ~ z-}.

Linguistically, a whole new contemporary episode theorized by the Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer initiates has painted a picture quite different from the perspective the Vietnamese people used to visualize, look at, and see themselves through the mirror of legends and folklores. Those scientifically-minded Indo-European linguists have not cared much more about factual historical data, let alone spiritual values to that the Viets have devoted their conviction for certain of particular issues. For instance, the Austroasiatic camp would not buy into those interpretive numbers such as total years of the 18 reigns ruled by their ancestral King Hung I, II, III... of the Viets, which is illogical, leaving a large gap of hundreds of years in the speculative span of more than 4896 years since 2879 B.C., the birthyear of their nation as they believe, which is hard to prove, simply all numbers not adding up logically, and so on. (H) Similar to the case of "Vănlang", the irony of history of Vietnam is that her people could not be sure how to say with certainty even the names of their legendarily-revered ancestral kings, specifically, that is, King Hùng or King Lạc (?) Two of the important, but intriguing, names are those of the kings called King "Hùng" 雄 (Mand. Xióng) and King "Lạc" 雒 (Mand. Luó). "Hùng" is the Sino-Vietnamese pronunciation mainly based on ĐạiViệt Sửký Toànthư (大越歷史全書 'Complete History of DaiViet') by Ngô Sĩ Liên following records in Chinese Annals where "Hùng" 雄 might have been mistaken for "Lạc" 雒 based on recent research showing that "Vua Hùng" were derived from Daic language called "pòkhun" where "pò-" is "bố" { ~> "vua" } (king) (Nguyễn Ngọc San. 1993. p. 93).

The Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer followers hit on the weather-beaten trails pioneered by their predecessors which first had their stand underwritten by the French academics. After the French colonists physically withdrew from Indo-China in 1954, the colonial legacy they left behind has been the most precious treasure being the Vietnam's national Romanized orthography called 'Quốcngữ' (國語) that came with the extra bonus of the grammatical mechanics from the French language that render today solid and logical { Subject + Verb + Object } models for the modern Vietnamese language, not to mention advanced intellectual tools and innovative methodologies, which pushes today's Vietnamese further from their ancestral language. It should be noted that the phenomenon was exactly like what happened in the academic field of the past right after the return of the Ming's occupation of the country in the 15th century for another 25 years added to the top of the Chinese colonization of the Vietnnamese land from 111 B.C. to 939 A.D.

As the readers will see in this survey the Sino-Tibetan-classified Vietnamese theorization has been based on linguistic particularities such as historical phonologies and etymologies along side with other prehistoric background of the hypothetical indigenous homeland — the same base that the Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer hypothesis has analytically employed on a constant basis with new researches having been published plentifully during the last six decades — its currency, however, has been on and off in the historical linguistic circle due to its lack of plausibly identified Sino-Tibetan ~ Vietnamese cognates. In fact the old hypothesis had been built on premises of Sinitic-based vocabularies and its fundamentally etymological breakthrough ceased to show its novelty for decades after its inception. As time goes by, fallout from the rainwash under the Austroasiatic sky would become much more of the re-enforcement to the Western theory on related Vietnamese linguistic matters. The author of this research would hope to change the century-long attitude of "business as usual" on this matter. That is, Chapter Ten with elaboration on Sino-Tibetan ~ Vietnamese cognates based on Shafer's long recognized Sino-Tibetan etymology work (1972) will vividly bring the century-old theory back onto the Sino-Tibetan ~ Vietnamese radar screen.

Everything comes with a price, though, such as the agony being endured by the Viets who have undergone through process of Austroasiatic 'mental colonization' that is comparable, spiritually, to the feeling of being coerced into making a compromise on one's own belief, or at least personal conviction, they have to trade in oriental philosophy on 'the Way of life' ('Nhânsinhquan' 人生觀 or Dao 道), all for what is kown as Occidental values. At the same time, collective subconsciousness of conflicting values will explicatively make them suspicious of any foreign work that hid an ideological agenda under different guises, e.g., based on historical experiences of Chinese and French colonization coming from different sources, say, possibly highly on the list being Russia or even the US as well. Needles to say, academically, such a perspective would be having a negative impact on social sciences or other humanity disciplines, including archaeology and historical linguistics.

Anthropologically, among those native ethnic minorities who have initially made up the main ethnic majority of Vietnam's population, the Kinh people are the majority who are, specifically, racially-mixed fusion of Sinicized people. In fact, since the days Annam had been still a China's prefecture intermarriages among migrants of different racial background coming from north and south of China have resulted in the emergence of the Kinh majority who preferred to reside around the Red River Delta, for most of the times living side by side where the ruling class resettled in, including the northeastern coastal area of today's North Vietnam with fertile paddy fields and fishing villages. In effect, the Han 'conquistadors' had been descents of the aboriginal Yue people who were originally rice planters in delta regions of cultivated paddy fields south of the Yangtze River such as Jiangxi (江西), Hubei (湖北), Hunan (湖南) provinces, and fishmen along the China's southeastern coast, i.e., ancient states of WuYue (吳越), MinYue (閩越), NanYue (南越). In the back of their mind, nonetheless, they are well aware that their ancestors were of the Yue genealogical line, with linkage to the largest indigenous population as popularly known today as the Zhuang (壯族 'Nùng') and the Daic (傣族 'Tày') minority groups, both concentrating in the regions of today's Yunnan (雲南) and Guizhou (桂州) provinces, along with those who are living in Guangxi (廣西) as well as Vietnam's northwestern region of Laichâu, Hàgiang, Tuyênquang provinces. For those Muong ethnic groups they are inhabiting the region further in the south far away from the coastal paddy fields, metropolises, or townships such as those remote mountainous regions of Hoàbình and Ninhbình.

On a grand scale, all of the above are related to the other Sinicized Yue groups who had long become parts of the Han Chinese majority such as those Cantonese, the Fukienese, or the Wu speakers in Guangdong, Fujian, and Zhejiang provinces. Linguistically, on the one hand, nobody ever questioned their Yue languages, i.e., 粵語 Yueyu, 閩越語 Min-Yueyu, 吳粵語 Wu-Yueyu, respectively, for having been totally Sinicized within the Sinosphere at least 2,500 years each; therefor, they have been classified into the Sino-Tibertan linguistic family. On the other hand, the Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer theorists did that with the contemporary Vietnamese by crediting extant non-Austroasiatic-origin Vietnamese words as Chinese loans because the ancient Annamese land had been under the Chinese rule 1100 years before its separation from NanHan State in 939. Interestingly, the core words in Vietnamese were solidly recorded in Chinese scripts in ancient times ever since they had been first invented, e.g., 'ngày' 日 rì (day), 'suối' 川 chuāng (creek), 'rựa' 戉 yuè (axe), 'gạo' 稻 gào (rice), 'dê' 羊 yáng (goat), etc., all quite distinctively different from comparative analysis base by those of the Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer groups, (See the chapter on the Mon-Khmer association) In comparison, the Mon-Khmer component in the Vietnamese linguistic map is really small in many aspects, mostly in substratum.