Vietnamese Chinese

What Makes Chinese so Vietnamese?

An Introduction to Sinitic-Vietnamese Studies

(Ýthức mới về nguồngốc tiếngViệt)

DRAFT

Table of Contents

dchph

Chapter One

I) Introduction

I am going to introduce some new findings in the study field of Vietnamese (V) etymology to be called Sinitic-Vietnamese (VS) (S) with a great number of words that are either derived from or sharing with northern Chinese Mandarin (M) as a result of its localization and innovation by speakers in the colonial government in Annam, now northern Vietnam. The term Sinitic-Vietnamese may also embrace another class of Vietnamese vocabulary, best known as Sino-Vietnamese (SV), that in turn had its deep root in Middle Chinese (MC) that was changed over time by officials serving imperial rulers from northern China. Like any southern Chinese dialects such as Cantonese or Fukienese, those Sinitic, or Chinese, components constitute most of the Vietnamese linguistic aspects today. In this survey, we shall focus mainly on the Sinitic-Vietnamese words which can be traced as far back into the linguistic past of Old Chinese (OC), which is in turn affiliated with the Sino-Tbetan linguisitc family (ST). For those fundamental Vietnamese cognates found in the latter Sino-Tibetan languages, they appear to have descended from Taic-Yue language family that had existed in the China South (華南 Hoanam) region long before the Chinese.

Etymologically, even though many commonly cited basic words in Vietnamese are currently considered as from Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer subfamily (AA MK) of a larger Austric family by the historical linguistic world; yet, it is postulated that all of them must have evolved from the same roots that once belonged to Taic-Yue strata, an ancient language family at least ancestral to proto-Vietic or Annamese (Annamite) and Daic, including those currently being grouped as Chinese dialects in the Sino-Tibetan linguistic family such as Cantonese and Fukienese. Why is their division? Their nominal difference lies in the fact that that is implicitly due to their synchronic nature in classification. For example, 'Sinitic' was derived from the name of the "Qin" State in the 3rd century B.C.; however, the same concept is embraced to refer to those pre-Chin(a) or proto-Chinese entities way far back not only beyond the Qin Dynasty but remotely surpassed the Shang-Xia Dynasties up to 5000 years ago. As for the modern Vietnamese it started to form in the 12th century (Nguyễn Tài Cẩn. 1978. See Appendix I), we may be able to step back and identify most of Sinitic-Vietnamese words from extracted data of the last 3000 years before present (B.P.) based on available Chinese historical records. Beyond that period there had existed hypotheses from many early authors such as De Lacouperie (1887) and specialists from the Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer camp.

The following introductory sections will give readers a preliminary preview of what should be expected throughout this elongate work. Primarily, the author will go over main points covered throughout the paper and, at the same time, build a rapport with some good examples of Sinitic-Vietnamese words to entertain readers by which many of them have never encountered before with respect to their Sinitic or Sino-Tibetan etymology because many etyma were mislabeled as of Mon-Khmer (MK) origin. Secondarily, even though it is not the main objective of this paper but its what is called the next level of achiement in the field, undeniably prominent Sino-Tibetan etymological evidences (see Chapter 10 - Parallels with the Sino-Tibetan languages can be used to renew a long standing issue of whether or not we should consider to re-classify Vietnamese into the Sino-Tibetan linguistic family (ST). The first revelation ever in this field of study with ample Sino-Tibetan evidences result from the forthcoming comparative work presented hereafter are based on the newly found Vietnamese words in Sino-Tibetan languages. That said, the author will be focusing not only on Vietnamese and Chinese cognates but also those found in Sino-Tibetan etymologies. The new findings will lend supports to the Sino-Tibetan theorization to rebut existing Austroasiatic theories on the Mon-Khmer origin (AA-MK) of the Vietnamese language. Lastly, some housekeeping for terminologies and conventions, and so on, will need our attention to make sure that we will be on track talking about the Sinitic-Vietnamese subjects on the same terms.

A) What makes Chinese so Vietnamese?

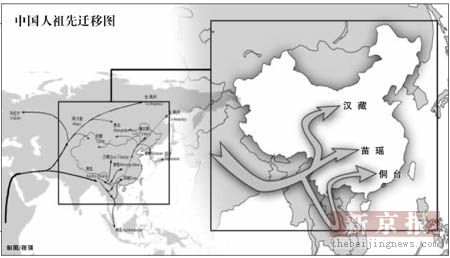

For posing such an intriguing question above, the subject matter of this section is built on the premise that in the prehistoric period in the region of China South (華南) there first had existed the ancient Yue aborigines and then the early Chinese emerged from the fusion of the Yue natives with those of the proto-Tibetan people who advanced from southwestern plateau. Altogether they were parts of all other populace in other states in the B.C. period prior to their being totally conquered by the Qin State (秦國). The subsequent collapse of the short-lived Qin Empire (221 B.C.-207 B.C.) gave rise to both the Han Empire (漢朝) in the north and the NamViet Kingdom (南越王國) further in the south and with the former having conquered the latter in 111 B.C. Not until 1050 years later in 939 A.D., the ancient Annam prefecture, located in today's North Vietnam, separated the ancestral Yue's territory under the rule of NanHan State (南漢國) to become an independent state after a long period under the Chinese rule with heavy Sinicization. Populace of Annam were descendants of the racial admixture of the early Yue and the later Han colonialists who had overstayed their mission in the southern land to have avoided the war-ravaged turmoils in the mainland in the last decades prior to and after the collapse of the Tang Dynasty. The Vietnam's history, hence, has been that of survivors of those Han sojouners and Southern Yue people all having emigrated from the China South region (CS). While the modern name 'Việtnam' as best known today means the "Yue people of the South", on their way advancing toward the south, they mixed further with local people and, altogether, they made up the Kinh majority. In other words, like the 'Chinese', no people are "pure" Vietnamese.

The introduction in this chapter on the Yue entities in ancient Annam will be elaborated with the history of ancient China that supports the theorization that

(1) the Sinitic elements emerged only after the Yue entities had been in existence, e.g., the Zodiac table of 12 animals, '/krong/' (river) for 江 jiang

(2) the Yue forms in the Sinitic language subfamily of the Sino-Tibetan linguistic family are attested by nearly all fundamental words in Vietnamese, e.g., 'gà' (chicken) for 雞 jī, 'ngà' (tusk) 牙 yá, etc., and

(3) the Sinitic-Vietnamese lexicons in the Vietnamese language came into existence after the Han colonial periods, e.g., 房 fáng for 'buồng' (room), 車 chē for 'xe' (carriage). (See Chinese cognates with ancient Vietnamese words)

As opposed to 'Sinitic', the term 'Yue' as transribed in Chinese variants 越, 粵, 戉, 鉞... used in this paper is to denote indigenous linguistic strata with fundamental words on which the proto-Vietic language had evolved and spread to various pre-Han forms as well, that is, an older ancestral form of Archaic Chinese (ArC) in the 'pre-Qin' era hundreds of years B.P., of which the latter Sino-Tibetan and Sinitic variant etyma later had abundance of time to have made multiple round trips back (and forth) to contribute more into the ancient Vietnamese vocabularies and vice versa, under different appearance. In effect, historical records indicate that both aboriginal Yue and proto-Chinese lexical items by then would have blended well into an admixture of what was known as a common diplomatic language called Yáyǔ (雅語) used among ancient pre-China's states as recorded in Chinese annals; that probably was the Taic-origin speech spoken by subjects of the Chu State (楚國) in the Spring and Autumn Period (春秋時代), B.C., which was the mother-tongue that had given rise to all other Daic-Kadai languages that the Dai and Thai people speak at present. Meanwhile, Yue is descent linguistic subfamily of the Taic, that has also formed what is known as ancestral Vietnamese roots. The author hence finds it appropriate to entitle this paper as What Makes Chinese So Vietnamese? (工) to spring forth the fact that there first had existed the Yue and only then came the Chinese on the Flowery Land.

The ancient Annamese — a historical name for that of the 'ancient Vietnamese' — language emerged with the Old Chinese forms of the later Western Han (206 B.C. to 24 A.D.) had been brought into the Annamese land by the Han colonialists. Linguistically, elements of Ancient Chinese of the era that followed. (T) As Annam became a sovereignty in 939 A.D., it continued to use Chinese characters, though, called ChữNho (儒字), or Classical Chinese 文言文, as her writing system. In the meanwhile, the Vietnamese language as we recognized it had not fully formed until the 12th century (See also Nguyễn Ngọc San. 1993, p. 5). In the 15th century Vietnamese literary works were found to be written in another modified form of Chinese-character-based scripts known as ChữNôm (𡨸喃) (字). In the 18th century when the Western missionaries came to the country to propagandize the Gospel, they encountered difficulties in learning the complicate Vietnamized Chinese scripts, so they created the Romanized Vietnamese system. Since the early 20th century their new writing system based on the Latin alphabets had gained popular acceptance for its ease of use and even though it was not officially adopted by governmental decree until 1945. However, such national script is called 'Quốcngữ' had earlier won full support of the French colonial government that eagerly wanted to drive out Chinese influence in Annam. In essence, the new medium of writing was actually only to transcribe all the Vietnamese and HánNôm (漢喃) words, the latter of which consist of both categories of Sinitic-Vietnamese (漢喃) and Sino-Vietnamese (漢越), into the new Romanized forms, whence the French lexicons left barely a few of residues as we see now.

Bùi Khánh-Thế in his article (printed in the scientific journal of Tập san khoa học Trường ĐHKHXH&NV — National University of HCM City, issue 38. 2007. pp. 3–10. regarding the interaction and interchange of the Chinese language throughout Vietnam's history, the author quoted Nguyễn Tài Cẩn (1998) as summed up the table below.

Table 1. Division of Historical Periods in the Development of the Vietnamese language

| A) | Proto-Vietnamese | 2 languages in use: Ancient Chinese (a vernacular Mandarin spoken by the ruling class) and Vietnamese; 1 Chinese writing script |

the 8th and 9th centuries |

| B) | Archaic Vietnamese | 2 languages in use: Ancient Chinese and Archaic Vietnamese (spoken by the ruling class); 1 Chinese writing script |

the 10th, 11th, and 12th centuries |

| C) | Ancient Vietnamese | 2 languages in use: Ancient Vietnamese and Classical Chinese; 2 Chinese and Chinese-based Nôm scripts |

the 13th, 14th, 15th, and 16th centuries |

| D) | Middle Vietnamese | 2 languages in use: Middle Vietnamese and Classical Written Chinese; 3 Chinese writing scripts: Chinese and Nôm scripts, and National Romanized Quốcngữ writing system |

the 17th, 18th, and the first 1/2 of the 19th centuries |

| E) | Early contemporary Vietnamese | 3 languages in use: French, Vietnamese and Classical Written Chinese; 4 writing scripts: French, Chinese, Nôm, National Romanized Quốcngữ writing systems |

during the rule of the French colonial government |

| F) | Modern Vietnamese | 1 language in use: Vietnamese; 1 National Romanized Quốcngữ writing system |

From 1945 until present |

Based on the formation of the Hán-Việt pronunciation of the Middle Chinese, Annam dịchngữ (安南譯語 Translated Annamese Words) and the Annamese-Latin-Portugese Dictionary by Alexandre de Rhode (1651), H. Maspéro devised similar division of 5 development periods:

A) Proto-Việt (prior to the 9th century)

B) Archaic Vietnamese: the 10th century (formation of the Hán-Việt)

C) Ancient Vietnamese: the 15th century (Annam Dịchngữ)

D) Middle Vietnamese: the 17th century (Dictionary by A. de Rhôde 1651)

E) Contemporary Vietnamese (19th century)

Source: Table 1 by Nguyễn Tài Cẩn (1998, p. 8) quoted by Bùi Khánh-Thế. (See Appendix I)

What is introduced in this preliminary preview will be elaborated on and expanded further in the next chapters. Our goal is to establish groundwork for the theory that both Chinese and Vietnamese fundamental words that shared the same Yue etyma, which is known in Vietnamese as 'Việt' (越 Yuè) and in Cantonese as 'Jyet6' (粵 Yuè), grew on top of the Sino-Tibetan stratum where the historical Chinese language of the later period were made up the classical literary language with many native words collected in Yayu (雅語 - See De Lacouperie, 1887) might have been derived mainly from the Chu language (楚國語) and had been a de facto diplomatic language among ancient states in the Spring and Autumn Period (春秋時代, 771 B.C.-403 B.C.), and it evolved into Old Chinese, Ancient Chinese, and Middle Chinese. After the Qin State unified and ruled the mainland of China, the Sintic linguistic elements flowed back and penetrated into several major Yue languages to have evolved into highly Sinicized Yue speeches, such as those of the Wu, Fukienese, Cantonese, Vietnamese languages, that is, all with Sinitic elements were supplanted on top of the original Yue soil. Such linguistic cycles can help explain the existence of Vietnamese cognates with the Sino-Tibetan fundamental etyma and, like other aforementioned Yue languages, they also made up the Sinitic linguistic subfamily until Annamese went its own way after independence in the 10th century.

For over the span of hundreds of years that followed, for the fact that the native Yue roots of common aboriginal etyma as found in Old Chinese and Ancient Chinese had synchronically returned to the Sinitic speeches and became parts of their vocabulary, overall, their lexical appearance were "re-packaged" under different forms. Besides sharing tonal values that spread from 3 to 10 tones across all Sinitic languages, their other linguistic characteristics even show only subtle discrepancies in articulation in regional vocabularies that grossly encompass nearly all lexical doublets — words from the same root — especially from proto-Taic, Taic, and Daic-Katai, e.g., 'kao' or 'gạo' for 'dào' 稻 (rice), elephant, whale, fox, rhinoceros, etc. (see APPENDIX G: Tsu-lin Mei, The case of "ngà"), names of the twelve animals in the well-known Chinese zodiac table found themselves recyled and re-used in other minority languages in China South, not to mention minor variants, except for the item 'hare' 兔 tù (VS thỏ), other eleven of the respective animals in the modern Vietnamese language are noted that they originated from some common indigenous languages, which are attested by the same etyma used by ethnic groups living in China South. As a matter of fact, recycled lexicological materials show in as recent as in our contemporary time as attested in the linguistic exchange among regional languages, e.g., Chinese-based Japanese words of modern concepts such as 共和 gònghé (republic) and 民主 mínzhǔ (democratic) were borrowed back into Chinese, as mentioned earlier

As seen through the usage frequency of Chinese and Vietnamese cognates in fundamental realm, which is both appear to contain residues of basic words from the "Yue" stratum. Such course of linguistic interchanges in effect had taken place long before the Qin and Han (漢朝 206 B.C.-220 A.D.) empires ever expanded to colonize the China South (華南) region. Many of such words were also positively identified in attested contexts in the Chinese Kangxi Dictionary (康熙字典), a monumental work compiled by great scholars in the Qing Dynasty under an imperial decree issued by Emperor Kangxi. (Y)

Archeaological artifacts and historical records show that in the ancient times the whole region of today's China South below the Yangtze River (長江) was the native habitat of the ancient Yue aborigines. Throughout the Zhou Dynasty (1045 B.C. to 256 B.C.) toward the end of the late Eastern Zhou Dynasty in 221 B.C., those indigenous people made up the population in each of the seven states that later were eventually all defeated by the Qin one, the strongest state of all that swallowed the other six into a unified Middle Kingdom (中國). While all those Taic-Yue natives had become subjects of the populace of the Qin Dynasty (秦朝, 221 BC- 207 BC), and then the succeeded Han empires, as a result, most of them later called themselves 'Han' (Chinese) being named after the Han Dynasty (漢朝) founded by King Liu Bang (劉邦), who himself was originally a Chu subject (楚國人) as well. Successors of the Han Dynasty continued to push the untamed Yue natives in the China South region and persued them further to the south. In that Annamese land that was later ruled by the Han, there existed no longer clear-cut distinction of the old Yue from late Han Chinese but only from the most influx of Chinese immigrants who fled to the southern country after all historical upheavals that accompanied the rise and fall of different dynasties one after another in the northern mainland of China. What is still going on has remained the embattled Vietnam of the present day, the only survival state on top of the ruins built the forerunners — of whatever left out of the diminished Chu, Shu, Yue, NanYue, Dali, Nanzhao, etc., to say the least — representative of the Southern Yue descents of which its populace are now called Vietnamese or 'the people of Việtnam'. Ironically, history has found that the same process that has formed the Chinese expansionists repeated itself long after Vietnam became a sovereign. The later Vietnamese would keep expanding their territory further to the south at the annihilation of the Kingdom of Champa and the annexation of partial eastern territorial flank of the old Khmer Empire.

In many facets history of both countries have been intertwined with each other until Annam successfully broke away from China. The written history of Vietnam had never been compiled by her own historians pretty long after the 10th century. What had happened before that period was mainly based on Chinese annals without cross references. Likewise, linguistically, research on the Vietnamese or Chinese linguistics will be insufficient if that of the other is left outin our discussions, especially for those of Old Chinese and Sinitic-Vietnamese etyma along with their shared linguistic peculiarities (See Wangli, 1957.) In effect, ancient Vietnam had been effectively a prefecture of China known as Annam for more than 1000 years prior to 939 A.D. Such a historical note will help explain why there exists a massive amount of Middle Chinese loanwords in the Vietnamese language. The last historical linguistic stage that followed the disintegration of Nan-Han State (南漢) in post-Tang era influenced greatly the formation of the Vietnamese language, on the one hand, by having brought learned vocabulary used by mandarins and scholars in the imperial court to the common mass by a larger scale to have become the everyday language, on the other hand, that made Middle-Chinese stock in Vietnamese somehow to appear similar to Cantonese for its full preservation of Middle Chinese 8-toned system, especially the 8th Entering Tone (入聲 Rusheng). To get the records straigth though, actually Vietnamese is more like Mandarin in terms of its colloquial usages of vernacular nothern Chinese Mandarin than Cantonese, not to mention its peculiarly phonological /-owng/ finals. We will return to the matter of Mandarin's likelihood later in this paper.

In any case, that is not all what makes Chinese so Vietnamese. Something else very much older had existed as Yue linguistic elements only in archaic forms being buried underneath the heavy Sinitic camouflage that has made so many indigenous Taic-Yue words to be mistaken as Chinese that, for the same matter in Vietnamese. Meanwhile, on the contrary, they are treated as "thuầnViệt" or "pure Vietnamese". Given Vietnamese as representative of the Yue survivor descents as previously mentioned, ancient Yue linguistic vestiges are pronounced in special Vietnamese way of those Chinese variations that are, in a way, sound modulators for those toneless words in several other Sino-Tibetan languages. So, while its Yue-origin words were masked as Chinese, the Taic-Yue words that made their way into Sinitic languages were shown in ancient proto-Vietic language. That is how "Vietnamese", or "Yue" to be exact, is regarded as to have existed before the early Sino-Tibetan speakers as forefathers of the Chinese moved in the China South region. For that matter, we will examine all the fundamental cognates with Taic-Yue, Chinese, and Vietnamese etyma being found across many Sino-Tibetan etymologies in detail in Chapter 10 .(未)

Let us return now to what we have just touched on above regarding words of higher-level in Middle Chinese — in similarly contextual usage in both Cantonese and Vietnamese — prior to the Tang Dynasty (618-906) that have become the indispensable Sino-Vietnamese stock in the Vietnamese language. Technically speaking, Sino-Vietnamese and Sinitic-Vietnamese are of two distinct lexical classes with the latter one having many layers of doublets piled up on top the former ones as a result of vernacular forms of Mandarin that has stretched out at least from the Han Dynasty through the Ming Dynasty in the 15th century.

Respectively, vocabularies identified in the Sino-Vietnamese realm could also be overlapped by those of the Sinitic-Vietnamese as well, though, because the extension of rich Middle Chinese vocabulary stock as attested in spoken Vietnamese that have been so widely used on daily basis by the common mass. The cited examples below illustrate a process of how those Sino-Vietnamese lexicons have been localized to make them sound like native words, hence, they becoming Sinitic-Vietnamese, i.e., no longer retaining the original meanings, a phenomenon more being more commplace in Janpanse Kanji than in Sino-Vietnamese, though, e.g., 'lịchsự' (polite) < '歴事 lìshì' (originally 'experience') or 'tửtế' (kind) < '仔細 zǐxì' ('meticulously'), etc; otherwise, they are of a larger set of vocabulary stock of Chinese origin being localized by systematic pronunciation that had evolved directly from a variety of Middle Chinese, assumingly postulated as close as to an ancient Shaanxi (陜西) dialect spoken in Chang'an 長安, the old capital of the Tang Empire in today's Xi'an City (西安市).

As the ancient Vietnamese evolved into the late Middle Vietnamese language needed then were functional words to construct sentences that imitated French grammar structurally as late as the early 20th centry. On its becoming coloquial speech, lexically, the Sino-Vietnamese vocabularies which must have come from a vernacular form of the Tang Dynasty (618–907 A.D.) as it might be still reserved somewhat in the highly Sinicizing style as, comparabale to the spoken Cantonese language. As recently as the 16th century, many Middle Chinese words transformed into the Sinitic-Vietnamese grammatical function words (虛辭) — equivalents of English although, not, in, at, from, and, hence, herewith, albeit, etc. — that evolved into linguistic necessity for non-flectional cases in grammar for both Vietnamese or Chinese (See Nguyen Ngoc San. 1993. pp. 138-142). As a matter of fact, ancient Vietnamese had used the classical Chinese (文言文) style (文) — which had been in use since the Tang Dynasty and diminished as late as toward the end of the 19th century — what sounds somewhat mystic in Tang-styled poetic stanza and overly cryptic in Vietnamese literary proses prior to the development of romanized Quốcngữ accompanied by its newly written transformation with a colloquial style (See Nguyễn Thị Chân-Quỳnh. 1995).

Comparatively, in Vietnamese there exist Sinitic components similar to what Middle Chinese has contributed to the makeup of Cantonese or, further into the remote past, Han's Old Chinese to the other Minnan subdialects, i.e., Fukienese, Amoy, Hainanese, or Chaozhou. Both Han and Tang lexicons contributed more new words into the Sinitic-Vietnamese vocabulary in the cycling patterns that recurred in the Vietnamese language in the later time. Given the fact that the two major southern dialects have been crowned with a Sinitic brand in the Sino-Tibetan linguistic family and that the principle of linguistic essence will rule based on major linguistic attributes and characteristics (cf. Latin-dominated French or bare-bone Anglo-Saxon of the English language, or Australian English vs. Indian English, and so on so forth.), all find similar linguistic models as such, e.g., hybrid Bulgarian, Africaan vs. Dutch, or Latin-French vs. Gaulish, Haitiian French vs. Marocan French..., the same theoretical principle can be equally applied to Vietnamese throughout our work about linguistic classification of Sinitic-dominant Vietnamese. It is, however, not up to any Sino-Tibetan theorists to go for in full force to clearly label Vietnamese as one of those in the Sino-Tibetan linguistic family with ample etymological support, or even simply of the Sinitic branch by just following the Cantonese model, though.

For the Sino- or Sinitic- prefixes being used to denote the concept "Chinese" in the linguistic classification, let us not be blindfolded by the name as it is being called. Sometimes it is nominally just a matter of academic convenience, especially for the western scholars, to designate an already widely accepted name, in this case, to call the entity "Chinese" even though it did not exist in the timeframe it is referred to, given the archeaological fact that the Yue entities had already been in existence long before what was considered as of China that emerged along with its subsequent aforementioned linguistic elements that came into being. In other words, it is an academic technique to make use of pre-existing terminology currently affixed to a popular domain name so as to conveniently refer to its prenatal forms that are well-known to the academic world. Such naming convention for conceptual designation is normally accepted in historical linguistic circles, especially in this case, because people know "Chinese" but might not have heard about "Yue". For the same matter, they may not buy the idea if the term is referenced with "Việt" or even /Jyet8/, herein with "Vietnamese" in the title of the book instead of "Yue". That is what makes Vietnamese so Chinese.

In terms of the frequency of lexical usage both Sinitic-Vietnamese and Sino-Vietnamese classes are on equal footing with and complementary to each other in the Vietnamese language by choice. Both sets of vocabularies are equally used in all walks of life, not only for literary writings in old and modern Vietnamese but also daily speech by the common people in all social settings. The fact that similarities in many fixed expression usages found in Vietnamese are still being used in modern Mandarin suggests that Early Mandarin could be a concurrent speech used by the mandarins in conducting official business such as imperial decrees, legal documentation, or reports to the Tang's imperial court in Chang'an (長安) (安), which had been more than once served as officially written language used in government and diplomatic communiqué (See Table-1 above by Nguyễn Tài Cẩn.)(W)

Intrinsically, each class of vocabulary stock is embedded with a history of its own becoming. Terminologically, the core linguistic term of 'Sinitic-Vietnamese' (VS), specifically used in this paper, indicates a mixture of basic items buried in the Yue substrate with Old Chinese (OC) elements on top of it in addition to other lexicons in the 'Sino-Vietnamese' (SV) class of Middle Chinese (MC) loanwords.

To wrap up for what is expected to come, let us start with the baseline first. It is universally reckoned in the academic world that (1) the "proto-Chinese" (Sino-Tibetan) never existed in places where they are now about 5000 years B.P., (2) Chinese has never been a race but culture and, interestingly, its history is that of emigrants who, each individual and everyone accounted for in the mainland of China, always want to get out of that flowery yet repressive kingdom, (3) for a rather ancient entity that Indo-European scholars prefer to call "Austro-Asiatic", it is de facto the Yue that had existed therein before the newcomers moved in who later became "Chinese". In this paper, the former are indigenous natives being referred to as "Taic" that gave rise to both (a) Daic-Kadai and (b) Yue, and (c) Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer = Taic+Yue entities while the latter evolved into what known as (d) Sino-Tibetan = Taic + proto-Tibetan, and (e) Han = Taic + Yue + Sino-Tibetan, (f) Vietnamese = Yue + Han.

Linguistically, on examining all of prevalent "Sinitic" pecularities that exist in the Vietnamese etyma, e.g., tonality, morpheme, phonology, dissyllabicism, and virtually the rest of subtle linguistic attributes in all word classes, most observers hold a strong inclination for their Chinese origin — exactly like the case of those designated supposedly Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer or Daic Katai words in Vietnamese — because when an etymon posited as it appears, the linguistic rule states that the closer the cognates appear, the greater chance they are loanwords. All attributes do not match certain sound change patterns or semantics at the same time, though, such as Thai /kao/ vs. Viet. /gạo/ (rice) with '稻 dào' (SV đạo) instead of 'lúa' (husky rice grain) as posited by the late renown Russian linguist A. Starostin. The axiom may or may not be true for the whole etyma. It is so said for in some other cases, antithetically, at times an etymon derived from a morphemic syllable that falls into the linguistic category of "words" is governed only by phonologically interchanging paradigms that, at the same time, display other linguistic features but tonality that do not match in many stances of which each derivative is still considered as a loanword for its apparent affinity, e.g., 兒 ér (SV nhi) > VS 'nhỏ' for 'child', hence, VS 'nhí' for 'baby' and 'nhínhảnh' with 'nhảnh' being a reduplicative morphemic syllable for the concept of 'childish' in Vietnamese like English "-ish" in this specific case, so we can conclude that the etymon 'nhi' originated from Middle Chinese and its other cited derivatives hence derived from the same source, all Chinese loanwords.

Both Vietnamese literary and coloquial forms from the Tang's speech were blended well into Annamese — as Vietnamese has been avoided being called as such due to its modernness as opposed to the same issue of the aforesaid terminology "Chinese" (H) — that have practically been widely used in different social settings including the common mass, past and present, not limited only to the circle of literati, to be exact. Such historical fact explains why the systematic Han-Viet or Sino-Vietnamese version and popular usage of its Middle Chinese vocabularies continue living on beyond the independence mark of the 10th century to have given birth to Ancient Vietnamese and become an integrative part of the Middle Vietnamese language and modern Vietnamese as we see it. (差)

With regards to other southern Chinese dialects, contrary to the common belief with the exception that thei tonal values carry similar ranges up to 9 tones, Vietnamese otherwise is more in line with Mandarin than all Cantonese, or Minnan and Wu subdialects, especially in lexical respects. In effect, only a few indigenous 'Cantonese' words were found cognate to those of 'thuầnViệt' or basic native Vietnamese, e.g., Cant. equivalents of 'sihk5' with Viet. 'xơi' (eat), 'jahm3' ~ 'uống' (drink), 'kâj5' ~ 'gà' (chicken) ... versus the rare cases of 'fajng1kao1', 'pin5tow2', or 'tzuo3' that do not go with 'ngủ' (sleep), 'nơinào' (where), or 'rồi' (already), with the Mandarin cognates only, that is, 卧 wò, 哪裏 náli, or 了liăo, espectively.

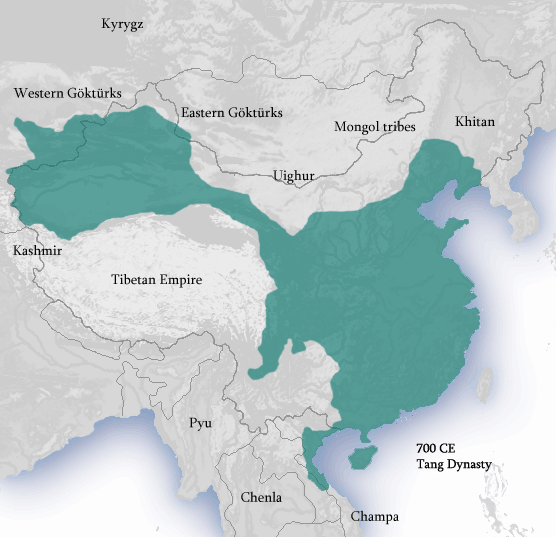

Figure 1.1: Tang Dynasty 700 AD

Source: from "The T'ang Dynasty, 618-906 A.D.-Boundaries of 700 A.D." Albert Herrmann (1935). History and Commercial Atlas of China. Harvard University Press.

Similarly shared Yue etyma above could also probably be traced back further into remote ancient times when proto-Tibetan and ancestral Yue languages both were blended with the later Viet-Muong that in turn had roots in the Taic linguistic family. Proto-Yue languages once had been widely spoken by the aboriginals inhabiting a vast region of China South (華南), overlapping some parts of faraway regions in China North along northern banks of the Yangtze River (揚子江), which is also known as the Changjiang (長江), as ranging habitats of the ancient Taic indigenous people who gave birth to the Yue people ('BáchViệt' 百越 BaiYue, the term possibly derived from 'Bod' ). (華) To be clear, the Yue, like the Eastern Yue (東越)and the Southern Yue(南越), were not ancestors of the contemporary Daic people but both were descended from the same ancestral Taic family. Altogether, racial admixture of the Taic-Yue aboriginals and proto-Tibetan nomads who had moved in from the southwestern China gave rise to what was later known as the Sino-Tibetan entities and, hence, the proto-Chinese who established the Xia Dynasty approximately some 5000 years ago. Further down the line for more than 4000 years later, the subjects of the newly unified empire of Qin State (秦國 206 B.C.) consisted of the Chu State (楚國) populace of Taic-Daic people, and, along with the Yue descents who made up the population of the southern Yue (越國) and the Wu (吳國) vassal states of the Western Zhou Dynasty. When the Han faction took over the Middle Kingdom from the Qin State, including territories in China South, linguistically, subjects of the whole Han Empire must have been decreed to use the same official court's language (X) spoken by the founder of the Han Dynasty, King Liu Bang (劉邦) who had been originally a Chu subject, like his generals and followers under arms, all could have spoken the Chu dialect, that is a Taic-Daiclanguage, so did the Yue people, ancestral Zhuang people, further in the south after the annexation of the NamViet Kingdom (南越王國) in 204 B.C. — "Nam" (南) to mean 'south' and "Việt" (越) to mean "Yue" or /Jyuet8/, both characters pronounced somewhat similarly in both Vietnamese and Cantonese in the ancient times, so they are transcribed as such throughout — including ancestors of the early ancient "Cantonese" — who also called themselves as "Tang people" and "Vietnamese" is "the Yue people of the South". That would explain why they all shared at least etyma from the same ancient substrate.

Figure 1.2: Map of the Yangtze River Basin

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Map_of_the_Yangtze_River.gif

With respects to the proto-Vietic language, after the split of the Viet-Muong groups over the divide of those indigenous people who resisted to the Han's occupation of their ancestral land and those who submitted and collaborated with the Chinese colonizers, like that of the Cantonese speech, comparatively, the early Sino-Vietnamese development and its proactive adoption into the old Vietic language to have become an ancient form of early Annamese had gone all the way through many centuries long in transformational stages evolving into the Middle Vietnamese period, especially with that of active phrases absorbing variants of the Tang's language by the newly emerged Kinh elite group, that is, the process of localization of the Middle Chinese words and expressions in addition to some minor changes in phonology, syntax, and semantics. The whole process could have occurred before and continued on long after the end of the Tang Dynasty (618-906). For the whole process, the localization of adapted Middle Chinese exical stock throughout the periods of colonization, which corresponded to the state of Chinese lexicography that had gone through volatile periods from the Han to the Tang dynasties in terms of phonological to semantic crystalization (Tang Lan. 1965. p. 110).

Having deeply shared the same historical background, analytically, Sino-Vietnamese and Cantonese sound change patterns that had evolved from Middle Chinese apparently followed the same phonological paradigms in both literary, e.g., literature or academics, and spoken forms at least until the 10th century before each language finally veered off their common path, i.e., sharing the same lingo-franco of the 'NamHan Kingdom' (Southern Han - 南漢), as each had gone its own way until their vocabulary stock later either disappeared with some lexical redundancy of doublets or gradually stablized as they appear in both Sino-Vietnamese stock at one hand and the so-called Tang's language as commonly referred to Cantonese in our contemporary time. For general readers Sinitic-Vietnamese etyma normally look indiscriminate not only to the naked eyes of untrained novices in linguistics but even tho those of language teachers with respects to sound changes and their etymological deviations, formally and colloquially. The author so said because he happened to survey a few school bilingual tearchers in general fields such as languages arts or ESL classes in US schools, they honestly admitted they had never noticed the similar lexical interchages between the two languages at all. For example, all of them have had no ideas that instances that Sino-Vietnamese word 'quốcgia' 國家 guójiā (nation) corresponds to Cantonese /gok7ga5/ (nation). While laymen in historical linguistics may be able to recognize such phenomenon of their interchanges by regularity rules, it is quite possible that the very same audience would vehemently argue against the variance of Sinitic-Vietnamese form 'nướcnhà', surely a cognate derived from the same root like 'quốcgia' but under the context that the concrete homonyms "nước" (water) plus "nhà" (home) have formed an abstract word that conveys more of the meaning of "country", not to mention a newly derived concept of 'body of government' called "nhànước", a reverse syllabic-morphemic word form, to say the least.

Long after the 'NamHan Kingdom' (南漢帝國) ceased to exist in 971 A.D., even though Annam had been separated, spatially and temporally, from its control since 939the then Cantonese and the Sino-Vietnamese, anthropologically, could have still shared a lot of physical similarities directly from the late Tang speech even though the two languages must have been already distinguishable from one another — as they analogously do now with the people in Guangxi Autonomous region with the localized version of Cantonese they called Baihua (白話). However, in our contemporary era, that would no longer be the case for the Cantonese-speaking descents living within the parameter of old Southern Han (the same old name as Guandong Province is still being called.) As a matter of fact the Cantonese speakers had been highly Sinicized by their multi-tiered blood mixture with the "Tang's Chinese" from the far north after hundreds of years under the rules of different dynasties in China, the China South region as a whole and Guangzhou prefecture, specifically, faced with massive waves of migratory move from the other region caused by raging wars — the An Lushan's Rebellion War in Tang's Ming Huang's reign that killed and displaces millions of people, for example (see Bo Yang, 1982-1992, Vol. 49 — and hungers that shifted racial balance. Their speeches, as a result, experienced the same life cycles of inevitable changes. In other words, up until the 10th century, it was highly probable that the Cantonese speakers in Guangzhou and Annamese speakers in Tonkin could communicate with each other verbally in some Sinicized speech such as Yue's Baihua (白話).

Besides, with respect to their common aboriginal root, etymologically, several Cantonese basic words such as 'hâj2' (be), 'pin5tow2' (where), 'majt7je6' (what), 'fajng1kao1' (sleep), 'kuj2' (tired), etc., may exist only in Cantonese while in Vietnamese those words might have been replaced with early Chinese which later were grouped into the Sinitic-Vietnamese category that will be the main subject focused in this paper. In the aboriginal layer of Yue that some Cantonese fundamental etyma sharing with Vietnamese such as 'lưỡi' 脷 Cant./lej6/ (tongue), 'bông' 花 /fa1/ (flower), 'biếu' 畀 bì /pej3/ (give), 'khui' 開 /hoj5/ (open), 'xơi' 食 /sik8/ (eat), 'uống' 飲 /jam3/ (drink), 'thấy' 睇 /t'aj3/ (see), 'đéo' 屌 /tjew3/ (fuck), or 'ỉa' 屙 /o5/ (to poop), etc., still remain only a smaller shared portion of Yue indigenous elements, though, which could be Taic-Yue remnants in both Vietnamese and Cantonese. For example, for 雞公 jīgōng, VS 'gàtrống' /ga2ʈowŋʷ5/ that corresponds to archaic Cantonese /kaj5koŋʷ1/ (rooster) is a rare but solid proof to identify their Yue linguistic affiliation in the lowest substrate, syntactically; both had been of the same root before being Sinicized. Specifically for the same sytaxtic matter, the modern grammatical order of [adjective + noun], e.g., M 公雞 gōngjī, is of Sinitic elements having grown on top of an aboriginal Yue linguistic substratum where both entities shared more similarities when they were still at monosyllabic stagein language development.

Nowadays, Vietnamese and Cantonese linguistic shares of semantics and syntax might be no longer be the case, e.g., VS 'gàtrống' vs. ancient Cant./kâj1kong1/ (鶏公), that they used to be close to one another for historical reasons. Respectively, both languages had emerged from different Taic-Yue branches long before their speakers became common subjects of the NamViet Kingdom (南越王國), aka 'Southern Han', in 204 B.C. In addition, the discrepancy between the two related languages also lies in the degree of influentiality of both the Han prior to 111 B.C. and thereafter and the Middle Chinese factors from the 7th century onward asserted on each language with permanent marks. For example, the Vietnamese still use 'đôiđũa', cognate of the Han's usage of 箸子 zhúzi for 'chopsticks' while the Cantonese, like Mandarin speakers, call them /faj1zej3/ or Mandarin kuàizi (筷子); however, in most of the cases, the pronunciation of Cantonese 走 /zow3/ derived from the Middle Chinese, and its usage is likely the same as that of Mandarin to mean "go" while in Sino Vietnamese 'tẩu' /təw3/ means "run" that is in turn equivalent to 去 qù or Cantonese /hoj6/ which is cognate to Sino-Vietnamese doublets 'khu' /kʰu1/, 'khử' /kʰɨ3/, 'khứ' /kʰɨ6/, and its VS variants 'khừ', 'khự', 'khử', 'khứa', including 'đi' (go) (cf. Hanoi subdialect /xɨ6/), with various meanings that originated from that of Ancient Chinese of the Han's period, expanding to convey the meaning 'eliminate', 'get rid', 'cut off'.

Categorically, however, regardless of its ancestral Yue root, Cantonese is sill classified as one of the Sino-Tibetan languages, correctly though, mainly for their prominent Sinitic elements with Middle Chinese lexical forms which overwhelmingly surpass ancient Yue etyma (cf. Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer presence in Vietnamese). There is no wonder Cantonese has unofficially been called 'the Tang language' (唐話 /Tong2wa4/). It seems that quantitative and qualitative factors weigh in here in judgement and designation of the Cantonese language under the Sino-Tibetan linguistic family. As previously mentioned, for the reason that the main lexical stock amassed in both Cantonese and Sino-Vietnamese in effect evolved from the same Middle Chinese source, on which the grouping of Cantonese into the Sino-Tibetan linguistic family were based, it is also logical to reconsider the possiblity to reclassify the Vietnamese language into the same family. The issue specifically brought up here is to purport comparative analyses with regard to relevancy of Sino-Vietnamese and Cantonese under Middle Chinese linguistic perspective as widely recognized.

Anthropologically, with respects to the Yue-before-Sinitic factor, according to some similar Zhuang and Vietnamese legends as to be told, either the Vietnamese (越 Viet) or Cantonese (粵 Jyet) populace might come out as descendants of different branch of the Yue (戉) prior to the second century B.C. (Z). The earlier 'Jyet' (白話 Báihuà) speakers, probably of the so-called Zhuang (壯族) origin, spread from the Guangdong (廣東) to the present Guangxi Province across the whole region historically known as the Southern Mountainous Range Region (嶺南道 Lingnan Dao). They inhabited a larger area of the ancient NamViet Kingdom (204 B.C.–111 B.C.) with its ancient capital situated in 'Phiênngung' (廣州番禺 present Guangzhou's Fanyu) ruled by the first king whom the Vietnamese called Triệu Đà (趙佗 Zhao Tuo) and his heirs. (V). After the whole Cantonese region, a part of the kingdom's territory, was annexed into the Middle Kingdom (中國), the Sinicization process that had started before 111 B.C. accelerated and continued on, which caused further deviation of Cantonese and Vietnamese as two distinctive entities, of which each had difted separately on each own destiny of historical journey that only Annam earned her independence from China's rule in 939 A.D.

Naturally, the modern Cantonese people's genetic tissues are not totally the same like those of their native ancestors prior to the annexation of the NamViet Kingdom into the Han Empire (111 B.C.) nor even decents of those who had been living therein whence up until around the 10th century because by that era, should their kins have emigrated to the Annamese land — so supposed because that must have regularly occured throughout the history of both nations (of which for China do you still remember the axiom that said "History of the Chinese people is of those China's mainlanders who always want to emigrate out of their native land to escap either hunger or repression whenever they have the chance!" while for the ancient Annamese they also advanced further to the south to flee from the China's historical long arms — they would have found themselves not much different from those locals under the same respective statehood then. It is also interesting to to note that the border beween China and Vietnam were widely open from the past until 1949 when Mao's communist regime was set up there.

Suppose that if Annam were still under the rule of China until present day, her national destiny would have long gone through the same development — fate, to be exact — that was bestowed onto the 'NamJyet' land (Canton) as now being called Guangdong Province, which, historically, had produced millions of emigrants to all over the globe, besides the adjacent Annam and other Southeast Asian countries since the ancient times. Reversely, if the greater 'Canton' region had gained its statehood like Annam in about the same period, it would have enjoyed status of sovereignty of an independent country and their language could have remained somewhat different like Annamese, so to speak, and it would have been questionable if being grouped into the Sino-Tibetan linguistic family, so would Fukienese and Hainanese and so on. Completely Sinicized modern Cantonese descendants could only see Canton's truly glorious past, sadly, though monumental museum of archaeological ruins of massive mausoleums built by kings of NamViet — by the way, the name spelling could be accurately as such as is pronounced where applicable — in China's city of Guangzhou today. It is so said in order to point out the fact that Cantonese is a completely Sinicized Yue language as opposed to Vietnamese at present time for the simple reason that the former one has been a Chinese province in one form or another continuously since 111 B.C. until now while the latter broke off from the China's colonial status since 939 A.D. as repeatedly emphasized throughout since its significance is tantamout to her national history as well.

For the magnitude of large-scaled immersive Sinicization process, tremendous impact from its fall-out that had stricken the ancient Canton region was much more extensive than what Chinese encroachers from the north could have committed on the Annam's soil even after her independence such as that of the Ming's 25-year rule of Vietnam in the 15th century, to say the least. The Chinese influential factor is a fact of life that has traversed her national history. Vietnam has been trying to balance herself in acting as vassal state depending on how the traditionally Chinese archenemy had up to its power in order to maintain her sovereignty even if more than 1000 years have passed by since the end of the total 1004 years her antecedent Annam had been under the colonial rule of imperial China.

The Vietnamese people are always nostalgic about the Yue heritage while many Cantonese speakers ignorant about it or completely deny their Yue roots even if they are. The Cantonese model is singly raised here because the case of Sinicization of Yue subjects (南越居民) in the NamViet Kingdom had taken a heavy toll on both ethnic and linguistic development of the ancient Yue people (越人). What happened in the Canton's region that was recorded in history as Ouyue (歐越) was similar to that of ancient Annan (安南), or LuoYue (雒越), given other historical events in the process of the Han's colonization that spread out into SôngHồng Basin, or the Red River Delta of today's northwest region of Vietnam, located further down in the southwestern part of NamVietn since the Han's conquest in 111 B.C. The Han's policy of colonization thereupon left permanent early Sintic birthmarks of the lately emerged Sinicized Yue speeches which, hundreds of years later, Cantonese and Vietnamese have become to be known of.

With all similarities of the Vietnamese and Cantonese languages, on the one hand, they still stop short of a one step further to have them bonded as kin to each other for we could barely find those newly discoverd Sinitic-Vietnamese etyma and the Chinese equivalents sharing the common ancestral root per se (Refer back to the legend of the Magic Sword that tells the story of the and Zhuang people — of coourse they did call themselves as the same same name then — as ancestors of the ancient Cantonese. (Z). On the other hand, for all Sino-Vietnamese etyma and those Sinitic vocabulary in Cantonese, their Chinese affiliation is affirmative, as a matter of fact without the need to prove them, attested in not only their usages of variants of Middle Chinese words but also their share of peculiar attributes and unique traits which make up linguistic commonalities such as tonality, e.g., 8-toned Vietnamese vs. 9-toned Cantonese, and phonological systems, e.g., endings -m, -p, -t, -k, etc.

Along with those Sino-Vietnamese words definitely evolved from Middle Chinese etyma, some had made long and round trips from ancient Yue to Old Chinese and passed down to Vietnamese, of which the Cantonese language lacks due to its overly shadow of Sinicization. For example, in the case of the cultural items such as the duodenary cycle of the twelve animals in the zodiac systems used by the Chinese, including those ethnic minority groups of China South, including Vietnam and southern Mon-Khmer cultures alike since ancient times. For example, any general reader with an average level of linguistic cognizance would readily accept the posit of 'mẹo', an older Sinitic-Vietnamese form of 卯 máo — that was later re-introduced into the Vietnamese culture as SV 'mão' — is for 'cat' (V mèo) originally etymologically, which is definitely not for 'hare' (兔 tù, SV thố, VS thỏ) as many Chinese Sinologists have tried to either to intentionally deceive or convince themselves and other Chinese fellowmen to believe.

Similarly, consider the case of 未 wèi for VS 'dê' /ze1/ (goat). It is possibly that 未 was descended from some ancient form sounding somewhat */ze1/ or */je1/ that must first have entered the Chinese language in duonary forms used in the zodiac system where the pronungciation of the character 未 is adapted to transcribe a foreign word for the animal 'goat' in place of the word 羊 yáng (northern Chinese nomads called 'sheep'). The Sinitic-Vietnamese 'dê' /je1/ indicated what 未would have sounded, that is, something close to that of modern Mandarin 'wèi' /wej4/ [ cf. SV 'vị' /vej6/ versus VS 'dê'/je1/ \ ¶ v- ~> z- (modern Vietnamese southern subdialect reflects more of ancient sound system than the contemporary nothern subdialect) ] that appeared hundreds of years after Middle Chinese /mwɤj2/ [ cf. SV(2) 'mùi' /muj2/ via ¶ /mjw- ~ w-(vj-/) ] rather than what were borrowed back from the Old Chinese /*mjəts/ [ 《說文》 未, 味也。|| Note: 味 wèi (SV 'vị', VS 'mùi' (taste) ] by the Yue populace of the NamViet Kingdom or the Annam State. Specifically, the character 未 wèi can be transliterated as both SV 'vị' to indicate both the SV 'mùi' as 'goat' as in 'Năm ẤtMùi" (Year of the Goat) and the later meaning 'upcoming'. While there existed no initial /v-/ in Chinese and Vietnamese in ancient times that would suggest it could have been pronounced as /jej/ in Vietnamese southern subdialect. It was possibly /wj-/, though. The Sinitic-Vietnamese form 'dê' /je1/, meanwhile, is also plausibly a doublet cognate to 羊 yáng (SV dương /jɨəŋ1/, cf. Tchewchow /yẽ/ or 'yeo', all with the same concept of 'goat' and 'sheep' by the northern Chinese). In terms of zodiac duonary forms, for the specific year 1955, 2015, 2075... its formal equivalent 乙未年 YǐWèinián (the 'Second' Year of the Goat) is more commonly known in modern Chinese as 羊年 Yángnián, meaning simply 'Year of the Goat'. As a matter of fact, while young Chinese nowadays may not recognize what 乙未年 YǐWèi Nián precisely is, ironically, Vietnamese youth mostly know exactly what "Năm ẤtMùi" means. The point to emphasize here is that 未 wèi in Chinese was possibly a loanword from an ancient Yue form plausibly reconstructed as */ʐẽ/ which has a different presentation from 羊 yáng, a pictograph that draws a shape of the head of a goat or sheep. Both 未 wèi and 羊 yáng could be an interchange for both the concept 'goat' and 'sheep' because they are related to not only the meaning but also phonology { as its etymology best demonstrated in the character 美 měi (SV mỹ /mej4/) 'beautiful' since 羊 yáng over 火 huǒ 'fire' of course makes some 'beautiful taste' whereas 美 měi and 未 wèi (cf. 'mùi' /muj2/) are also related in both sematics and etymology. } (Refer back to the Footnote (未))

For all those elaboration on the Vietnamese cognates with the two cases of zodiac animals in Chinese as exemplified above, their implications will be applicable to other similar Sino-Tibetan related linguistics researches, say, what comes next could be Viet. 'ngọ' ~ 'ngựa' 午 wǔ (horse),'sửu' ~ 'trâu' 丑 zhǒu (buffalo), etc. New approaches could be initiated to study possible the Vietnamese linguistic affiliation with those etymologies of Sino-Tibetan languages as to be illustrated later in this paper based on the wordlists tabulated in Shafer's works (1966-1974). For example, Vietnamese 'cẳng' for Old Tibetan (OB) 'rkań' (foot), 'mắt' OB mig (eye), 'sông' OB kluń (river) vs. Vietmuong */krong/, 'bò' OB 'ba' (cow), and so on so forth, all appear to have originally existed in or evolved into the Vietnamese language prior to Sinitic contamination in much later periods.

In fact, our new hypothesis as elaborated etymologically above could be postulated based on those Vietnamese etyma that have shown as Sino-Tibetan cognates as having directly been descended from other Sino-Tibetan languages rather than via any Chinese conveyance, too many of them to say they are coincidental. New theorization may in turn be proposed for some new linguistic classification of Sinitic-Vietnamese to be created in its own class. Perhaps that could be a sub-division to be put on par with the Sinitic branch — for the reason the the Yue having existed prior to the proto-Chinese as previously mentioned — of the Sino-Tibetan linguistic family (because those cited Vietnamese fundamental words in Chapter 10 appear to be cognate to all Sino-Tibetan etymologies as we go into detail.) To put everything in perspective, modern 'Chinese' dialects and their subdialects have been called 'Sinitic' — that is, the reason that 'dialects' of the Chinese language are of its Sinitic branch — because the terminology indicates a Sino-Tibetan related matter, academically, not because the "Sinitic" had existed before the "Yue".

Like that of "Sinitic", the term 'Yue' (M) — it would much precisely better be called 'Viet" — being used in this paper carries the implication that neither the ancient Yue aboriginals nor self-acclaimed descendants of the ancient LacViet (雒越 LuyoYue) people in our contemporary era, that is to say the Yue were not of descents from a pure race, neither were their languages. Linguistically, those Yue attributes and shared portions of indigenous etyma in the languages spoken by ethnic groups living in the regions of both the China South and North Vietnam would give rise to doublets as cognate variants as recorded in Chinese classics. For example, Kangxi Dictionary (康熙字典) recorded 淂 dé (SV đắc) that is related to the old Viet /dák/ to mean 'water' vs. 水 shuǐ (SV thuỷ, phonetically, cf. 踏 tă for VS 'đạp') of which the meaning of 'river' in turn appears in other forms such as 川 chuān or 江 jiāng for Vietnamese 'sông' or 'river'.

Doublets similar to those etyma are vestiges of some archaic speeches spoken by the native people living inside the perimeters of those ancient states which would later be annexed to become parts of the larger China, namely, those of Shu State (屬國), Chu State (楚國), Yue State (越國), and later the NamViet Kingdom (南越王國) of which their subjects were of the racial mixture of ancient LacViet (雒越), Xi'ou (西甌) or ÂuViet (歐越), and MinYue (閩越) or Dong'ou (東甌) tribal conglomerations.

Âu Việt

The Âu Việt (Chinese: 甌越) was a conglomeration of upland tribes living in what is today the mountainous regions of northernmost Vietnam, western Guangdong, and northern Guangxi, China, since at least the third century BCE. In the legends of the Tay [Daic] people, the western part of Âu Việt's land became the Nam Cương Kingdom, whose capital was located in what is today the Cao Bằng Province of Northeast Vietnam.

The Âu Việt were also referred to as the Dong'ou Kingdom (東甌), descendants of the state of Yue who had moved to Fujian after its fall. The Western Ou (西甌; pinyin: Xī Ōu; Tây meaning "western") were Baiyue tribes, with short hair and tattoos, who blackened their teeth and are the ancestors of the upland Tai-speaking minority groups in Vietnam such as the Nùng [Zhuang] and Tay [Daic], as well as the closely related Zhuang people of Guangxi.

The Âu Việt traded with the Lạc Việt, the inhabitants of the state of Văn Lang, located in the lowland plains to Âu Việt's south, in what is today the Red River Delta of northern Vietnam, until 258 B.C. or 257 B.C., when Thục Phán, the leader of an alliance of Âu Việt tribes, invaded Văn Lang and defeated the last Hùng king. He named the new nation "Âu Lạc", proclaiming himself "An Dương Vương" ("King An Dương").

The Qin dynasty conquered the state of Chu, unifying China. Qin abolished the noble status of the royal descendants of the state of Yue. After some years, Qin Shi Huang sent an army of 500,000 to conquer the West Ou, begain [sic] a three-year guerrilla war and killed their leader.

Before the Han dynasty, the East and West Ou regained independence. The Eastern Ou was attacked by the Minyue, and Emperor Wu of Han allowed them to move to between the Yangtze and the Huai River. The Western Ou paid tribute to Nanyue until it was conquered by the Han. Descendants of these kings later lost their royal status. Ou (區), Ou (歐) and Ouyang (歐陽) remain as family names.

The Chinese-Han people by then were the fusion of proto-Tibetan people who made up the Qin population that had been composed of populace from other 6 ancient states, especially the Chu subjects, consisting of all the Daic and Yue tribesmen, anthropologically. From the time the NamViet Kingdom was annexed to the Han Empire in 111 B.C. as subjects of the Han Empire were further mixed with the Yue people surpassing the Lingnan southern region and the same process repeated again and again in space and time.

The proportionate nature of the ethnic composition of the Han populace probably remained the same racial fusion like that of the Chu level by the time the Han Empire was established, yet, its overall population must have been less than before all preceeding wars. That is to say, the Yue-Daic factors were still dominant among the Han subjects after the Chu State lost its contention to the Han. It is so said because, hisorically, the Han's first King Liu Bang (劉邦) and his generals, subordinates, as well as most of their infantry as a combat arm, all had been of the Chu fighters against the Qin's army before the Han's final victory. The "Han" and Han-related entities evolved from a short form of Hanzhong (漢中), a remote prefecture in today's China's Shaanxi Province where Liu Bang had been bestowed as governor by the last Duke Xiang Yu (項羽) on behalf of the last King of Chu. They both turned against each others and for that reason that the winners did not consider themselves of the Chu subjects for a good reason, they called themselves the Han people; hence, the Han entities exist in parallel with the term "Chinese", a derivative of "China", along with "Sinitic" and "Sino" all from "Qin". They could be called by other names, Cathay, Tang, or Qing, etc., but the true nature of their racial mixture are that of a united of states of China.

Similarly, the long period of national developnment of Vietnam had begun with the biological makeup of the early Vietnamese people who had been descended from the racially mixed Yue — LacViet, XiLuo, OuLuo — of the NamViet Kingdom. It is unlikely that the Vietnamese people have been genetically pure as descendants directly straight from the already ancestral Yue tribemen aforementioned after 1004 years under the Chinese rule until 939 A.D. In addition, since her independence Annam's people had managed to govern their own sovereign state which is now called Việtnam (越南) that literally means 'The Yue of the South', not 'Advancing to the South' as some mistaken belief due to an interpretaion of the character 越 for what today's Vietnam's southern territory that kept expanding; the ancient Chinese transcribed sound of the name "Việt" or "越" as 'advance' or 'surpass", but that should be the transliterated sound recorded by Chinese history as 戉, 粵, 鉞, etc., the three words to mean a tool or weapon similar to 'axe'. However, after more than a millenium of the southward migratory movement, the contemporary Vietnamese have been a racial admixture of native people along the way already, that is, the Cham and the Mon-Khmer people, to be specific. Archaeological evidences and anthropological history point to such supposition.

Linguistically, new etymological survey put forth in this paper includes the historical perspective above in terms of synchrony and diachrony. The approach having been explored is more like random captures of motion-pictured frames in a long historical video clip and that could be set fast forwarding and rewinding, back and forth, zooming in and out, that we can elaborate on but the chronological timeframe may not be all clear with the etyma under examination, for instance., 'béo' (greasy) for 油 yóu as in 油膩 yóunì (VS 'béongậy') based on the pattern ¶ /y- ~ b-/ in the Mandarin /yóu/ sound coresspondences with these words 郵, 由, 柚, 游, etc., that all match nicely to those Sinitic-Vietnamese phonology, that is, 'bưu' (postal), 'bởi' (because), 'bưởi' (pomalo), 'bơi' (swim), respectively. The interchanges are plausible but how to come up with the latest sound splits is based on the new approach to be presented in later this book.

As attested in the Sino-Tibetan etymologies the diachronic transformation of the modern Vietnamese parallels to a theory about the early Southern Yue tribesmen who run their own countries across the China South before the Han dominion> The proto-Tibetans who had fanned out from ancient China's southwestern region where pcharged northward and mixed with the native people in the perimeter of the Shu State (蜀國)in today's Sichuan Province of China all the way up to area northeastern triburies of the Yangtze River, who have been assumed to be extinct based on archaeological excavation with their artifacts left in the ruins deep in the wilderness. They started the Yin-Shang Dynasty building up the Yin State (殷朝 or "NhàÂn", 1600 B.C.-1046 B.C.) that once invaded ancient Vietnam as recorded in her legend and the Chinese history as well In between 1220 B.C.-1225 B.C. Throughout the next two millennia the pre-Chinese blended with Taic-Yue people and gave birth to the so-called 'Chinese' that had begun before the pre-Qin-Han's era. For those Yue people who had split from the same Taic group like that of the same Daic ancestors who had established the Chu State, including the early ancestral Zhuang, or 'Bod', people who later made up the Yue State (越國) and Eastern Yue (東粤) states. As the "Ân" invaders advanced southward with so powerfully aggressive force, the Yue natives fled from their homestead emigrating southward. Both of these two major racial entities — Qin-Yue racial admixture in the length of some millenia — had encompassed both northern and southern migratory routes that covered all points of migratory routes from the pivot that spread from today's Yunnan to Zhejiang and Fujian provinces of China and from regions and then making an U-turn southward that covered Hubei, Jiangxi, and Jiangu provinces stretching down all the way to the southern hemispherical regions now being postulated in the Austric, Austronesian, Austroasiatic, and Autro-Thai hypotheses, anthropologically and linguistically. In short, languages in the whole region are related by any measure. The differences lie in the fact that they haved been called under different names. (See Terrien De Lacouperie. 1965 [1887] )

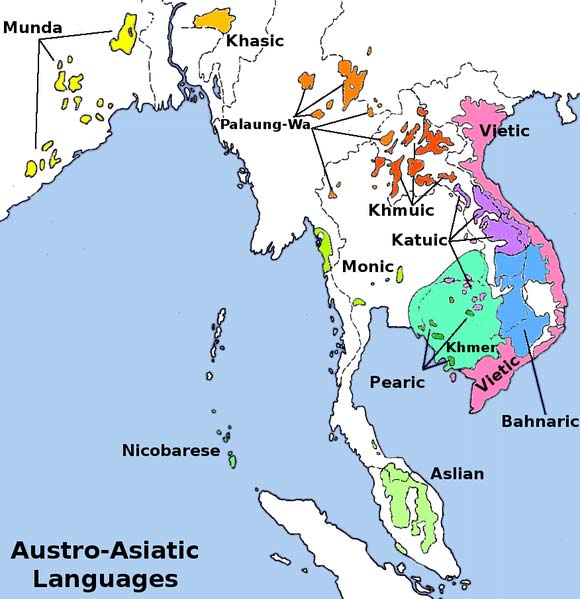

How has that given rise to the classification the Vietnamese language per the Austroasiatic theorists as of the Mon-Khmer linguistic sub-family then? How does it stack up with the Sino-Tibetan or the ancient Yue etymological evidences proposed in this paper at the same time, then? Under the ethnicity perspective, the Austroasiatic theorization took the position on the Mon-Khmer origin of the Vietnamese and their language mostly based on the formation of the Vietnam's ethnic minorities (who we considered as the latecomer.) Altogether, they are of Austroasiatic origin, large and small, that make up the total of 54 groups (to match the tally of the last 2010 census, among them many speak at least one Mon-Khmer language, such as those living along Vietnam's western mountainous ranges and southernmost territory.) (See the distribution map of the Austro-Asiatic languages before the Vietnamese migrated into the central region from the 12th century onward.)

With regards to the statement that the Mon-Khmer elements under our racial-component perspective they were only the latecomers, be reminded again that Vietnam has acquired the southernmost territory from the ancient Khmer Kingdom for only 310 years as of now. In the contemporary era the territorial area in the Vietnam's geo-political map is historically much larger multiple times than what used to belong to the ancient Annamese land of 2 millennia ago, excluding what is to be compared with the historical part of the old region of the NamViet Kingdom that consisted of today's Guangdong Province of China. Seeing through the Austroasiatic perspective, today's Vietnam's territory embraces even more indigenous Mon-Khmer inhabitants of ethnic minorities living in within their old respective native landfor more than 2200 years before present (B.P.), or even the prehistoric period as postulated by the Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer theorists. To put everything in the scope of ethnicity, for over 85.7 percent of the Kinh populace make up the majority of the population of more than 91 million people, so to speak, the majority of them descended from a mixture of the Yue stock from the China South region before they further mixed up with the Chamic and the Khmer minorities south of the 16th parallel only after the 12th century. Linguistically, for what is found to be related to Sino-Tibetan linguistic family, those of Sintic-Vietnamese accounted for even more than 95% of the Vietnamese vocabulary stock in addition to both basic and fundamental words found in the earlier Taic origin that exist in all ancient languages involved, and, notably above all else, of which the same percentage of linguistic commonalities and peculiarities become their indispensable parts in the modern linguistic forms.

Archeaologically, specialists in the Austroasiatic camp theorized that the Indo-Chinese peninsula as the cradle of the Khmer origin where indigenous substratrum had revealed the Mon-Khmer basic words in Vietnamese and anything grew up on it was seen as Chinese loanwords brought in by emigrants from the China South who had immigrated to Vietnam. Their theorization aimed to negate the notion that the ancient Yue entities were just covered under the Austroasiatic guises. As a result, they missed the points that, firstly, the Yue and Austroasiatic people were possibly descended from the same root as those of the native people in China South and the fact that, secondly, the Vietnamese are made up of the racially mixed populace — Chinese of Yue origin from the China South and earlier resettlers in the Red River Delta having moved in from the southwest region whose Indigeneity turned out to be those who were postulated by the Austroasiatic camp as ancient Mon-Khmer speakers — who finally become new masters in their resettlements who built their own state in the southern land. In effect, the Vietnamese of the last mellenium were a racial admixture with the late Chamic and Khmer people whose ancestors had ealier inhabited in the vast region that has been incorporated into their geo-political map one by one since the 12th century.

The author's position on this issue is that, for whatever name it is called, it could be Austroasiatic that gave rise to those Mon-Khmer languages, but anything directly to ancestral language of today's Vietnamese (See Table 1 above). Anthropologically, before the Mon-Khmer people from the southwest region moved in, both groups of the aboriginals and new settlers could have been intermingled in the same locality and they all had been descended from the same Taic ancestors in the northern Vietnam's Red River's Delta area that stretched further to northern region of China South as discussed above. The whole scenario as such is only to explain the existence of the commonality of a few of shared basic words among Vietnamese and Mon-Khmer languages.

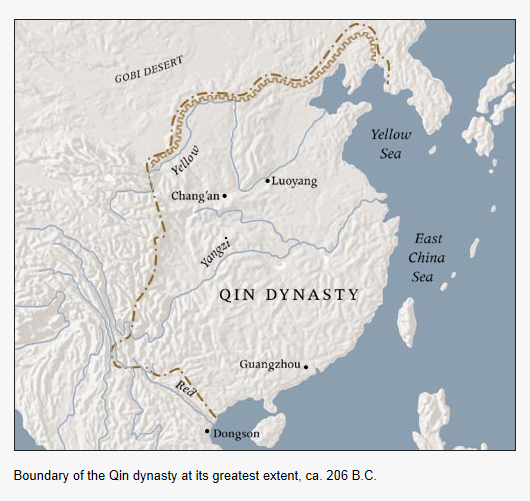

Figure 1.3:Map of territories of dynasties in China

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Territories_of_Dynasties_in_China.gif

In our specific Vietnamese case hereof, spatially and temporally, changes in migratiory movement of newcomers from the north to the south only caused displacements of indigenous natives from their home habitat, mostly from a fertile land to less arable mountainous regions. Those new resettlers from China South who moved in after the Qin-Han period also brought with them their own speeches that were mixed with the local Taic-Yue speech for the next 1000 years. It is probably that about 1200 years ago the people in both Annam and Canton within the NamHan Kingdom (南漢帝國) could probably be able to communicate with each other, at least with some vernacular form of regional Mandarin as attested in literarary words with the fully developed Hán-Việt (漢越), or Sino-Vietnamese, vocabularies that are supposedly descended directly from the Middle Chinese, especially during the last 289 years under the rule of the Tang Empire. Linguistically, that kind of fluidity in communication transition as proved by linguistic history has never been so with other Mon-Khmer speakers in any whatsoever manners except for the late influence that fell on those Muong ethnic groups who had them as their neighbors. In fact, the latter Muong groups were split from the Viet-Muong group who did not cooperate with the Han colonists and fled to remote mountainous regions and lived side by side with the Mon-Khmer speakers, as to be discussed in more details later in the next chapters.

In linguistic terms, as hosts and guests exchanged words, those originally native Yue elements would then become complementary to whatever already in the Sinitic domain, yet, those of the Sinitic entities did not replace the Yue linguistic characteristics of the native speech, which is analagous to the effect of whatever new concepts in Japanese that were created by utilizing Chinese material. Historical facts show that the early Chinese immigrants from the China South kept emigrating southward en masse to the Annamese land, especially not only during the 1000 years of Chinese colonial periods (111 B.C. to 939 A.D.) but also all the way through Vietnam's history of later period up past the 1949 mark until recently with all the Chinese laborers have resettled and worked in newly Chinatown-styled plant enclosure around the country at the very least. Nevertheless, while Chinese linguistic pecularities brought in by Chinese immigrants speaking different mainland's dialects had penetrated deeply into Vietnamese, e.g., tonality or phonology, of which their formation are similar to Cantonese, Tchewchow, Amoy, Hoikien, etc., they were intrinsic, not importing, e.g., values of tones or syllabic structure. Comparatively, that was how the whole process of linguistic changes had happened to Cantonese, specifically. After a long period of time, the Annamese language could only be able to retain a much smaller percentage of the Yue elements, though. So mentioned in such detail, the author would like to point out their Yue distinct commonalities, which is in total contrast with those of Mon-Khmer features against those of Vietnamese as their existing similarities in certain area simply a result in linguistic contact. It is suggested that the Mon-Khmer groups moved into the Red River Delta about 6000 years ago. (Nguyễn Ngọc San. 1993. p. 43)

Along with those either passing-on or added-on inheritance that cannot be excluded as sole Chinese factors, anthropologically, early immigrants from both the southwestern and northern neighbors of ancient Annam — located in Vietnam's today's northwest region, by then the northwestern and western stretches of land did not belong to Annam's geo-political map — had been actually of racially mixed of the Taic descents, i.e., supposedly descendants of the ancient Daic people. The same process kept recurring with other Mon-Khmer latecomers. The integration process of such immigrant aliens into the ethnicially mixed minorities would not have changed much of ethnicity balance of the Vietnam's nationals in the later period when the Annam nation had become a sovereignty, expanded its territory much deeper in the far west and further down to the south. It was not until the late 16th century, the western planks of the old Khmer Kingdom's territory were annexed to Vietnam with their populace counted as a minority group of Vietnam's nationals as of now. The same fate had fallen beforehand as previously mentioned for the Chamic natives along the Vietnam's Central coast below the 16th latitude that started since the 12th century and ended in the 18th century.

Anthropologically, those cultural artifacts excavated from their ancestral land were neither created by nor possessed by the forefathers who founded Annam, let alone the modern Vietnamese, so should their linguistic items be treated the same way. That is to say, the early Annamese language then basically could probably not changed much after long exposure to local speeches, assumedly, of Austronesian Chamic or Austroasitic Mon-Khmer origin except for having picked a few of local items, including basic lexicons along the southward migratory routes the early Annamese frequented and finally resettled. That was the becoming of the contemporary Vietnamese communities living along the Central coastline cities. For those new Vietnam's nationals of the late Ming citizens such as the Tchewchow refugees — who might be the group that gave us the derogatory term 'Tàu' (< 'Tiều' < Triều < 朝 Cháo < 潮州 Tchewchow) as we know of in the modern Vietnamese language — as facing the advancement of the Qing's Manchurians to take over the mainland of China in the 17th century thousands of them fled south to the seas and finally having been resettled in southernmost part of the Vietnam. In other words, prior to the 12th to 17th centuries what happened in the region south of the 16th latitude had nothing do with ancient Vietnamese, anthropologically and linguistically, not matter what the Indo-Europeans, i.e., the Austroasiatic camp, said.

To understand argumentation above within a chronological scope of history, we hence need to crack the nutshell of both the prehistoric and historical period in both China and Vietnam of which the Austroasiatic theory missed the mark. The Yue entities should be examined from a historical perspective in order to see the whole linguistic picture that the modern Vietnamese has been a very late product, and getting out of the Mon-Khmer realm will reveal many Vietnamese fundamental words in the Sino-Tibetan etymologies and help revive the former Sino-Tibetan theory, which had never come to full term or out of age yet in late 19th century, into full swing in this 21st century.

Let us first try to put altogether a historical picture of the prehistoric thing that the period of approximately 5000 years ago in which the indigenous Yue — i.e, the Taic, or the proto-Yue, as either term being used for their prehistoric existence prior to its later being given the name Yue (越, 粵, 戉, 鉞, etc.) in Chinese history — had inhabited in the China South region prior to some speculated time that witnessed the arrivals of itinerant proto-Tibetan normads in search of good earth. The late proto-Chinese resettlers were warriors who conquered on horseback; they colonized, appropriated, ruled ancient vassals established in the flowery mainland by the indigenes which historically once evolved into powerful states. The latter crushed down all of them one after another over the rather long period of time by the subsequent dynasties of the Xia 夏, Yin 殷 (SV Ân), Shang 商, Zhou 周, and their vassal states of Qin 秦, Chu 楚, Yue 越, Wu 吳, Yan 燕, Qi 齊, etc., all of which were subjugated to the successive the Zhou kings (1045 B.C. to 256 B.C.). By the end of the late Eastern Zhou era in 221 B.C., the Qin conquered all other 6 remaning opponent states, and for the first time in history what was later known as China, a unified 'Middle Kingdom'. 'China', etymologically, emerged from the entities of the Cin, Chine, etc., a variant from 'Qin' (秦), so to speak.