Vietnamese Chinese

What Makes Chinese so Vietnamese?

An Introduction to Sinitic-Vietnamese Studies

(Ýthức mới về nguồngốc tiếngViệt)

DRAFT

Table of Contents

dchph

(Continued)

Chapter Six

VI) The Chinese connection

China? Chinese? What is it? Who are they? In what way are they related to the Vietnamese? How closely is Vietnamese affiliated those Chinese languages spoken in China historically? Why is it considered invasive to tout reflection of Chinese linguistic imprints in the Vietnamese language in light of its speakers having been long so conscious of their national identity? Under no circumstances could we take off the connection of their country's history from that of China and retain just what the Vietnamese like. Account of the birth of a nation could not be solely based on some invented account that was solely based on on-going innovative hypotheses and those based on make-me-feel-good folktales and legends by Vietnamese nationals such as unfounded 4000-year cultural history. (K) Similarly, with respects to the Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer theory on both Vietnamese and Khmer affiliation, its initiators mainly spoke of southern basic words with which they had built their case (W).

To complement on all other works built on such previous foundation, this survey is to explore records in those historical periods that can support linguistic facts. If linguists take lightly the historical issues that exist in their etymological realm, novices in the historical linguistic field will be tempted to take the same old road that their predecessors have gone before. There still exist many other unresolved methodological issues, admittedly though, on both old and newer theories that could damp down one's impartial view very much depending on where one stands.

In this chapter the author will attempt to answer the foregoing questions under the historical perspective by addressing and substantiating evidences for the argumentations that

- geo-political factors did bring about negligence and negation of factual records in terms of history and linguistics due to strong nationalism against all Chinese influences,

- there always exists unavoidably bitter antagonism inferring China's hegemonism, a sentiment that has interfered with impartial judgment on the becoming of the Vietnamese language in the early periods,

- the reason why it matters so much that Vietnamese etymology on the whole could be discriminately weighed on the Sinitic scale as its principal element in the Vietnamese linguistic development until presently in the postulation of the Chinese affiliation,

- in line with "natural selection" theory (Charles Darwin. 1859), the core Chinese linguistic elements in the Vietnamese language are actually transcendence of racial transformation from cross-marriages among the ancient Vietnamese indigenes and later Chinese resettlers – mutated interminglings – which has in all capability been an on-going process since the prehistoric times,

and, if the Austroasiatic theorists want to talk hypothetically about things that have taken place thousands of years agao, we also have something to counter, least but not last,

Each language has each own history of development. We can theorize onw by envisioning the origin and the becoming of the Yue, the Chinese languages, and their affiliated sub-families such as Sinitic of Sino-Tibetan or Mon-Khmer of Austroasiatic linguistic family. At the early day of the 18th century Sir William Jones (Merritt Ruhlen, The Origin of Language. Ibid. 1944 [1994]. p.27) has first postulated an Indo-European family by identifying the commonalities of the Sanskrit, Greek, Latin all have sprung from the common source with other languages such as Gothic, Celtic, Persian and that was the result of his mastering 28 different languages to get that. Even before Jones, resemblances among languages have been recognized, but he realized that the similarities among them were due to their having each inherited these words independently from Proto-Indo-European. "His crowning achievement was not just that he saw these similarities, but that he explained them. And the evolutionary explanation he gave – descent with modification from a common ancestor – was the one Darwin would give 72 years later for biology." More than two centuries passed since Darwin and such a concept seems natural and obvious, but the static mode of thinking of the eighteen century was revolutionary. (Ruhlen. Ibid. p. 28)

The similarity of basic vocabulary of different language families determines their classifications, and hence their affinities. Darwin recognized this simple basic of biological taxonomy quite clearly in 1871 that "[i]f the two languages were found to resemble each other in multitude of words and points of construction, they would be universally recognized as having sprung fom a common source, notwithstanding that they differed greatly in some few words or points of construction." Unfortunately, it is a lesson that has been largely forgotten by historical linguists since the last 20th century. (Ruhlen. Ibid. pp. 135-136) Studies of the relationship between human genetics and comparative linguistics seem to be leading toward a better understanding of the origin and spread of modern humans around the earth. With the integration of all related fields such as the evolution of biology, archaeology, clearly, has a vital role to play in unraveling this intricate and complex history. Ruhlen saw it fit that we pay homage to Darwin, in the The Origin of Species (1859), he forsaw the biological and linguistic evolution would have to proceed the parallel lines: "If we possessed a perfect of pedigree of mankind, a genealogical arrangement of the race of man would afford the best classification of languages now spoken throughout the world; and if all extinct languages, and all intermediate and slowly changing dialects, were to be included, such an arrangement would be the only possible one." (Ruhlen. Ibid. pp. 159-160)

Stuffed with such a mindset, Ruhlen's approach is what we follow next on the theorization of the Yue as precedessors before the pre-Chinese set foot on the mainland of ancient China, anthrologically and linguistically.

A) The Chinese intruders

Regarding the pre-Chinese and the Chinese, Courrien de Lacouperie in The Languages of China before the Chinese (London 1887, reprinted Taiwan, 1966), theorized that the original Chinese neucleus consisted of about a dozen Bak tribes from the West of Asia and their tribesmen, to be accurately, the Bak leaders were more civilized than the normadic horsemen from the North who now we know of Altaic Turco-Mongolic origin (see Peter A. Boodberg, Ibid., 1979.) The Bak tribes were from the Southwest Asia, West of Hindukush; they had been under the influence of the civilizations of Susiana, an offshoot of Babylon. They all learned the elements of the arts, sciences, and government, including derivatives of cursive styles in writing. They reached the country some 2,300 years B.C. and, along with those Altaic tribes from the North into the basin of the Yellow River, they all fallen in with populaces of Southern origin. For many centuries the early Chinese established themselves in the region of today's Gansu and Shaanxi at the lattitude of Taiyuan because they could not cross the Southern bend of the Yellow River as they had met with forceful strongholds stationed by the Jung invaders from the North stationed there previously, that is, the barbaric Xiongnu (匈奴) as so called by in Chinese records. That was the period of King Shun (舜 2043-1990 B.C.) who had inherited the annexed territory in the Southwest Shaanxi ruled by King Yao (堯 2146-2043 B.C.). (Terrien de Lacouperie, 1966. Ibid. pp. 9-11)

As soon as the early pre-Chinese arrived in the new land, they interpersed individually or in groups in different directions in graduality infiltrating into aboriginal communes and established their dominion over the vast new territory. At the same time, other infiltrators from the north kept slipping into the south, joined hand with the indigenous tribes eitther in rebellion or under false suzerainty with the early Celestial government. Those who objected to the absorption were partly destroyed and partly driven southwards. Unlike the scattered aborignal tribes found in Tibetan borders, Taiwan, and the Philipine islands, the majority of people in Indo-China were formerly from China proper. "The ethnology of the peninsula cannot be understood separately from the Chinese formation" and vice versa. As a result, there is no doubt that the Chinese language were affected by the aboriginal ones while the latter were considered as distinct from what were known from the speech of the northern Altaic or Turko-Tartar former occupiers with that the early Chinese were NOT connected but the Western or Ugric division of Turanian class-family, and in the division it was allied with the Ostiak dialects." However, for a time the intermingling of the language of the conquerors with that of the previous inhabitants as they advanced into the South East towards the mouths of Yangtze River about 2000 B.C. during the Xia Dynasty. (Lacouperie, 1966. Ibid. pp. 12-14).

"[..]The aboriginal tribes, of the Flowery Land, with whom the Chinese Bak tribes, advancing through the modern Kansuh to South Shensi, fell into contact, did not receive them all in the same way. Some were friendly from the beginning, others objected to their advance, and the same thing occurred over and over again in the course of their history. Small and unimportant at first, the Chinese had no other superiority than that of their civilization. In their advance they had to make their way through the native settlements, either by amicable arrangements and interminglings, or, in case of need, by war and conquest, with the help of the friendly tribes. They used to establish advanced posts and military settlements, around which their colonists could take shelter when required by the hostile dispositions of the native populations among which they were interspersed. As a rule, in the history of their growth and development, the advance of their dominion was preceded by the settlements, always increasing, of colonists in the coveted region. It was their constant practice to drive away their lawless people, outcasts and criminals, who with the malcontents and the travelling merchants paved the way to the future official extension. The non-Chinese communities and states were in this way always gradually saturated with Chinese blood. This policy was never long departed from, even when in later times their power was sufficiently effective to permit a more effective way of bringing matters to a short conclusion.

Under the pressure of the Chinese growth by slow infiltration or open advance, the Pre-Chinese populations gradually retreated southwards; some of them were absorbed by intermingling; others, satisfied with the Chinese yoke, lost slowly their individuality, and formed part of the Chinese nation. Others were entrapped to the same end by the insidious process of the Chinese government, which, bestowing on their chiefs titles of nobility and badges of office, thus made them, sometimes against their secret will, Chinese officials. Light taxes and a nominal recognition of the Chinese suzerainty were only required from them as long as the government of the Middle Kingdom did not feel itself strong enough to ask more and overcome any possible resistance. But those of the Pre-Chinese who objected altogether to the Chinese dominion were thus gradually compelled to migrate away, either of their own will and where they chose and could, or, as was the case in later times, in such provinces or regions left unoccupied by the Chinese for that very purpose. Numerous were the tribes who were gradually led to migrate out of China altogether, as we have had many occasions to show in the course of this work.

The gradual submission of the Pre-Chinese was a very long affair, which began with the arrival of the Chinese Bak tribes, and has not yet come to an end, though the finish is not far at hand. For long the Chinese dominion was very small, and later on, when very large on the maps and in appearance, it was, as a matter of fact, effective only on a much smaller area. The advanced posts on the borders of the real Chinese domain used to give their names to regions sometimes entirely unsubdued, though the reverse has long seemed to be the case, because all the necessary intercourse between the independent populations and the Chinese government passed through the Chinese officials of these posts, specially appointed with great titles of office, for that purpose."

(Lacouperie. Idbid. pp. 106-108.)

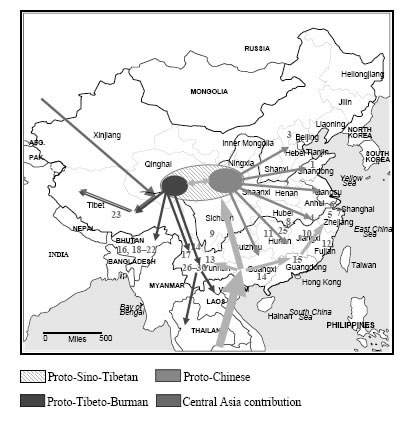

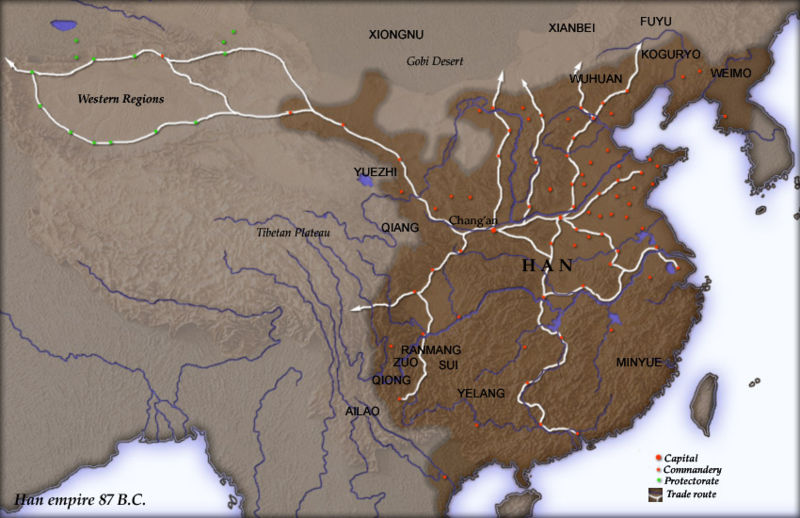

Figure 6.1. The Chinese Intruders

It is not one of the least interesting results of modern researches in oriental history and philology that the Chinese should now be known as intruders instead of aborigines in their own country. This blunt statement must, however, be qualified, as the modern Chinese are a hybrid race, andtheir speech is a hybrid language. both of which are the outcome of interminglings between the immigrants from the north-west and north and the previous occupiers of the soil belonging to different races, and especially to the Indo-Pacicific ones.

This better knowledge, for the benefit of the philosophy of history, was brought about by a closer examination of their early traditions, a rigorous identification of the geographical names mentioned, therein and in the course of their history, and the study of many historical statements and

disclosures about the non-Chinese races actually settled within the borders of China proper, clumsily arranged under the heading of foreign nations, in the Chinese Dynastic Annals.

The early Chinese intruders and civilizers were the Bak tribes, about sixteen in number, who arrived on the N.W. borders of China not long after the great rising which had taken place in S.W. Asia at the beginning of the twenty-third century B.C. in Susiana. Their former seat was within the dominating influence of the latter country, as they were acquainted with its civilization, a reflex of the Babylo-Assyrian focus."

(Lacouperie. Ibid. pp. 113-114)

Figure 6.2. The Other Intruders

"Numerous were the tribes and races who, for the same reasons as the Chinese Bak tribes, or attracted by the wealth and civilization of the latter, forced their way into China, imperilling the existence of its government, often superseding it altogether over a part or over the whole of the country, and afterwards disappearing, not however without leaving traces of their sway in the civilization, the language, and the population.

The Jungs, who had partly preceded the Chinese, the Teks, the Kiangs, etc., have been already mentioned in this work as having contributed to swell the ranks of the malcontents and banished Chinese families, as well as those of the aboriginal tribes, in pre-Chinese lands. Now we must refer more particularly to those of the intruders who have exercised an influence of some importance either politically or in civilization.

The oldest intruders of this class were the Shang 商, whose name suggests that they were traders, while their traditions indicate a western origin near the Kuen-lun range, and perhaps a parentship with the Jungs. They appear on the N.W. of the Chinese settlements since the beginning of and in the sixteenth century [B.C.]; they upset the Hia dynasty, took possession of the parts of Shensi, Shansi, and Honan then occupied by the Chinese, driving the Hia [廈 Xia] towards the coast.

The Tchou 周, formerly Tok, who drove away the Shang-Yn dynasty [殷 Yin], established their brilliant rule over the Middle Kingdom in 1050 B.C. ; some of them had lingered on the Chinese borders in Shensi for several centuries. They were, most probably Red-haired Kirghizes, and were not apparently without Aryan blood among them. It seems so, from the fact that they were acquainted with some notions derived from the Aryan focus of culture in Kwarism, which they introduced into China, and that several of the explanations added to the Olden texts of the Yn-King by their leader Wen-wang were certainly suggested by the homophony of Aryan words.

The Ts'in 秦, or better Tan [ SV "Tần" ], as formerly pronounced, formed an important state on the west of the Chinese agglomeration.

It grew from the tenth century to the third B.C., when, having subdued the six other principal states of the confederation, its prince founding the Chinese Empire, declared himself Emperor in 221 B.C. Their nucleus was not Chinese, and made of Jung tribes who absorbed gradually many Chinese families from inside, and also Turko-Tatar tribes from its outside borders, the limits of which are not well known. This state was a channel through which passed,

or a buffer preventing the passage of, any intercourse of the west with the Middle Kingdom."

(Lacouperie. Ibid. pp. 123-125)

We will elaborate more details in the historical facts of the hypothesis above which led linguistic formation of both Chinese and Vietnamese with the preliminary review of what could be used to support the author's argumentation on the historical development of Sinitic-Vietnamese etymology.

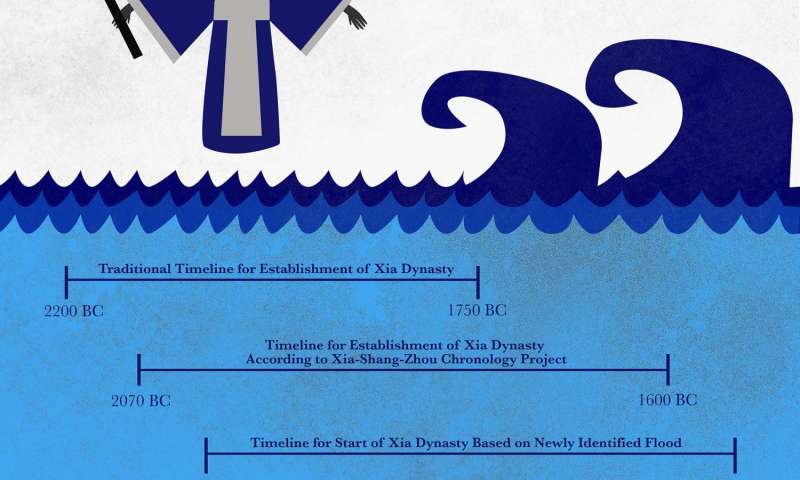

China's history of recorded contacts between the ancient BáchViệt (百越 BaiYue), i.e., the Yue people, or Peh Yueh, that is, 'all the outside-borders' as defined by Lacouperie (ibid. p. 116), and the China's historical Yin Era (殷代, or 'ĐờiÂn' in Vietnamese) early during the period of 1718 B.C.-1631 B.C. when they were at war with each other. By that time the Yin had long separated from the Tibetan (Bak) root and its subjects had long been resettling in the northwestern region of Gansu and Shaanxi. The Yin might be already an established state as archeaological excavation evidence as recently as August 2016 that proved the existence of its succeeding Xia 廈 and Shang 商 dynasties. (周)

Figure 6.3. Yin-Xia-Shang-Zhou timeline

The findings in the journal Science may help rewrite history because they not only show that a massive flood did occur, but that it was in 1920 B.C., several centuries later than traditionally thought.

This image highlights the variable timelines for the start of the Xia dynasty according to traditional Chinese culture, the Xia-Shang-Zhou Chronology Project and the flood that was newly identified and dated by Wu et al. (Credit: Copyright © Carla Schaffer/AAAS)

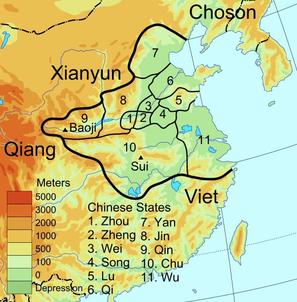

Following the fall of Xia and Shang dynasties, successors of the Yin, the Zhou Dynasty (周王朝) era emerged with the newly mixed populations with the Rong, Turko-Tartaric normadic tribes who established the Zhao 趙, Wei 衛, Liang 梁, Liao 遼... in the China North (華北) with all the subjects from the vassal states of Qin (秦), Lu (魯), Qi (齊), Yan (燕), Han (韓), in the Central Plains (中原), combined to have made up the people in the united China under the Qin rule in 221 B.C. Up until that time the "diplomatic language" among them was recorded in the Yayu (雅語), a dictionary of the local dialects, and Wenyanwen (文言文), or classical Chinese, both as their tools in interstate written communiqués. There is no need to say people did not speak the same languages then as now, so to speak. The northern languages were different from those spoken in the southern states of Chu (楚), Wu (吳), Yue (越), and later the XiYue (西越 TâyViệt), Dongyue (東越 ĐôngViệt), MinYue (閩越 MânViệt), WuYue (吳越 NgôViệt), LuoYue (鵅越 LạcViệt), OuYue (毆越 ÂuViệt), and Yuechang (越常 Việtthường), all were descended from a common root being referred as "the Taic linguistic family" in this research, as opposed to those of the Sino-Tibetan linguistic family as known today with the Chinese language. Meantime, the "Yue linguistic sub-family" is postulated as a branch that parallels with what the Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer linguistic sub-family was hypothesized, which are in opposition with the Daic-Kadai linguistic sub-family.

As a matter of fact, in the early 20th century the southern linguistic group was lumped together into the 'Austroasiatic linguistic family' (AA) by Western linguists which also embraced all those Mon-Khmer languages spoken Southeast Asia's region. However, like their cultural fossils excavated further in the southern Indo-China regions of today's Vietnam's territories, the Mon-Khmer or the Chamic languages spoken by the indigenous people there had nothing to do with the Annamese latecomers long after the 13th century when they set foot in the region. The Annamese by then had already spoken a form of Yue language with thick layers Chinese lingo which was unlike any of the Mon-Khmer languages but it must have sounded like a variation of vernacular Mandarin. So said, we are speaking of era recorded in history, not prehistoric periods.

History had it that as China ended with the Spring and Autumn Warring Period (春秋戰國, 770 BC - 221 BC), subjects of several states that were defeated by the Qin State (秦國) fled southwards to China South (華南), among whom were those of the Yue indigenous people – who were recorded in different Chinese characters such as 鉞, 粵, 越 (Việt), etc., and had long established their rightful aforementioned Yue states by then. The Chinese of the Northern states always contemptuously referred to those people as NamMan (南蠻) or "Southern Barbarians". All together the Yue tribes evolved into ethnic minorities in our time known as the Dai (傣), the Zhuang (壯), the Yao (瑤), the Miao (苗) (Hmong), the Mon (猛 or 毛南), etc., respectively, with their languages each having evolved separately.

Tracing down the family line, it is noted that the Chu State (楚國) had its subjects being of Taic descents (原始傣族 - Tai-Shan). When Chu – along with other several vassal states of the Eastern Zhou Dynasty (東周王朝) era – was defeated by the Qin State, all of its populace was absorbed into the Qin Empire. In 208 B.C., the Yue states from MinYue (閩越) to Vietnam's northern Giaochỉ (交趾) across a vast stretch of land in the China South, that were then ruled by the former Qin's general called Triệu Đà (趙佗 Zhào Tuó), would later be incorporated into the NamViệt Kingdom (南越王國) that lasted nearly 100 years until it was finally conquered by the Han Empire (大漢) in 111 B.C.

Essentially the racial components of the Han Empire consisted of mainly those who were from the combined populations of both the Chu and former Qin Empire's states in addition to the populace of the later annexed NamViet Kingdom. In other word, racial balance of the Han people, hence, was composed of basically the same Yue ethnic ratio based on the fact that the racial makeup of all the subjects of those states previously defeated and incorporated into the Qin Empire already having included a great number of people of Taic stock of the earlier Chu State. Again, be reminded that King Liu Bang (劉邦) who founded the Han Dynasty and his subordinates had been formerly subjects of the Chu State (楚國居民) as well.

As the Han Empire expanded with the annexation of the former NamViet Kingdom, part of it became the Giaochâu Prefecture (交州 Jiaozhou) that would later be known as the historical Pacified Southern Protectorate 安南都護府 (Annam Đôhộphủ), located in today's Vietnam's northeastern territory. In Annam in the advancement of the Han colonialists the indigenous Viet-Muong groups, descendants of the LuoYue (雒越) people – who originally inhabited inside the ancient Vănlang State (文郎國, a semi-legendary state postulated as under the rule of 18 ancient Vietnamese Hung kings 雄王, possiblly a misreading of the first Chinese character in 雒王 or "King Lac" ) considered as the early ancient Annam – defiant Muong people broke up and fled to remote mountainous regions. Those left behind in the lowland of the fertile Red River Delta formed the Kinh ethnicity (京族 Jingzu) majority. Many of the later Kinh people were born from intermarriages with the later Han resettlers who, except for those had deep and remote roots from China North, were also of Yue origin, e.g., descendants of the Chu State's subjects and those coming from the Eastern states of Wu and Yue, now belonging to Zhejiang and Jiangsu provinces. Note the connotation of the word "京" for "Kinh", which means "the metropolitan people", as the Annamese called themselves since the ancient times. In short, the ancient Annamese Kinh were formed with the interminglings of the "Yue-mixed Chinese" – from the Han subjects in China South – with the local aborigines in the Red River's Basin in North Vietnam.

Historically, since 208 B.C. onward, the language of the Qin Dynasty, e.g., 秦 as "Tần", had already impacted the indigenous Vietic language in the process of forming the early ancient Sinitic-Vietnamese vocabulary stock. Furthermore, the imposition of the Han's language around 186 A.D. as decreed by Viceroy Sĩ Nhiếp (士攝) over the use of the indigenous Yue language caused the Ancient Chinese basic stock to have continually penetrated deeply into the local fundamentally linguistic base. As more ancient Sintic elements continued to blend the cout's language of the mandarins as adopted by the changes of each dynasty in the Middle Kingdom with different colonial policies as late as the Ming Dynasty in the 14th century in Annam for a period of 25 years more under its rule. Their linguistic mixed use contributed to the shape-up of the Middle Vietnamese as spoken locally at the time. In short, long after the split of Viet-Muong group, the linguistic division between the Muong and the Kinh became much deeper and turned out to be unintelligible to each other as different languages in our contemporary era.

To sum up the total impact of those foreign intruders into Northern China and the pre-Chinese penitrators into the prehistoric land of the Yue in China South had on the linguistic aspects of Chinese, for the overall Chinese history, Terrien de Lacouperie wrapped it up nicely as follows.

"The influence of the Turko-Tatar races has been considerable. Several of them [...] belong to olden times. For several centuries after the Han period, ignorant Tatar dynasties have ruled over parts of Northern China. The Sien-pi, cognate to the Coreans, have produced the dynasties of the Former Yen, 303-352 A.D.; the After Yen, 383-408 A.D.; the Western Yen, 385-394 A.D.; the Southern Yen, 398-410 A.D.; the Southern Liang, 397-414 A.D.; the WesternTsin, 385-412 A.D.

The Hiung-nu Turks have produced the dynasties of Northern Liang, 397-439 A.D., of the Hia, 407-431 A.D. in W. Shensi (to be distinguished from the later Si-Hia), and afterwards the Northern Han, in 951-799 A.D.

The Tchao Turks produced the dynasties of the Former Tchao, 304-329 A.D., and After Tchao, 319-352 A.D.

The Si-fan have produced the dynasties of Tcheng in Szetchuen, 301-346 A.D. ; of the Former Tsin, 390-395 A.D., After Tsin, 384-417 A.D., both in Shensi. The Tobat Tatars, who produced the great dynasty of the Northern Wei, 386-532 A.D., belonged to the same group. They were apparently acquainted with the Syriac writing, at least about 476-500 A.D., and they had a court language of their own, in which their ruler Wan-ti at that time (in 486 A.D.) ordered that a translation of the Hiao king or 'Book of filial piety' should be made. Its use was not abolished before 517 A.D.

The rule of the Northern Wei extended over the whole of Northern China, with a few regional exceptions in the proximity of the Yang-tze Kiang. Later on, that of the Mongol dynasty of the K'itan or Liao, 907-1202 A.D., was restricted in the north-east. In the north-west, the Si-Hia or Tangut dynasty ruled from 982 to 1227, until it was swept away by the Mongols. [..] The Kin or Jutchih, the ancestors of the present Mandshu dynasty, ruled over a larger area than the N. Wei, from 1115 to 1234 A.D. The Mongol Yuen dynasty established by Kubila'i-Khan in 1271, and which lasted until 1367, was the first to rule over the whole of China; its great power did more for the homogeneity of the Middle Kingdom than any previous effort.And at last, in 1644, the Mandshu Ta Tsing dynasty established its sway all over the Empire[..]

These various dynasties brought each of them their own language, as their names suggest, and restricted as it was in its use to the court and soldiery, its influence was in every case limited, though by no means unreal, as shown by the alteration of pronunciation and the introduction of words in the official dialect. With regard to the [..] Maudshus, their presence has hurried on the phonetic decay of the Peking Mandarin dialect, now the official language, on the path of hissing and hushing the sounds, where it had entered since the days of the Yuen Mongols. Their small number, and their habit of living somewhat apart from the population, restrict the influence of the soldiery, which is felt only in the proximity of the post-towns over the empire, by the introduction of a few terms in the vernaculars."

(Terrien de Lacouperie. Ibid. pp. 127-129)

With regard to Taic roots of the language that subjects of ancient Chu State spoke, including King Liu Bang (漢高祖劉邦), the founder of the Han Dynasty, and his generals who helped found the Han Empire as discussed earlier more than once in the previous chapters, the Sinitic-Vietnamese fundamental words shared some of them from the descendant Daic-Kadai family, of which variant dialects are spoken by the "Tày" ethnic groups in North Vietnam. This Sinitic-Vietnamese linguistic survey will show that my newly-found dscovery, including those of the earlier period, i.e., the glossarial vestiges of the proto-Taic elements that existed in the pre-Sinitic linguistic being older than Archaic Chinese forms as found in the Minnan dialects in MinYue (閩越) State, located in today's Fujian Province of China as they are linguistically affiliated with some basic words found in the Yue aboriginal language. (See Chapter 7 on the Tày worldlist.)

B) Is it Chinese or Vietnamese?

It is not always easy to identify the oriigin of a cognate in both Sinitic-Vietnamese and Chinese. What is the appropriate way to classify a "Sinitic-Vietnamese word" if it originated from either the Yue root or Archaic Chinese via its cognateness with both roots, such as those that have evolved into lexical variants or derivatives, e.g., 牙 yá originally a Yue word meaning 'tusk' which became 'tooth' in Chinese? (See APPENDIX G: Tsu-lin Mei's The Case of "ngà". If it was of Yue origin, should the Chinese form be then considered as an Yue loanword or a cognate of the same Sinitic-Vietnamese etymon affiliated with some indigenous "proto-Yue" or "Taic" linguistic family? As a matter of fact, a native basic word could distance itself from other forms which are likely related as well, not only the case of 牙 yá. For example, an indigenous form *krong are cognate to both Vietnamese 'sông' and Chinese 江 jiāng (SV giang, Cant. /kong11/, 'river', as in "Mekong" and 湄江 Méijiāng), the word 江 being an irreplaceable word in Chinese but having a deep root of some ancient Yue language in China South. By the way, in Khmer the modern form "krong" means "city", though, such as 'Krong Siem Riap'. Phonologically, the specific phonetic shell that "wraps up" the etyma evolved from *krong in Vietnamese 'sông', SV 'giang', Cant. /kong11/, M 江 'jiāng', etc., are constructed with the vocable constructed with the toneme[C+V(+C)] that compasses all existing Vietnamese and Chinese vocabularies; every morphemic attribute – such as its tonality – of a Vietnamese lexeme /sowŋ11/ or /səwŋ11/ is characteristically of the same nature of the ancient root */krowŋ11/. So said, by the same analogy, M 江 'jiāng could have its root in 水 shuǐ (SV thuỷ) of Tibetan tchu origin or the Chinese 川 chuān (SV xuyên), both meaning 'river' as well (See Chapter 9).

Such a linguistic build is parallel to that of genetic stock forming the same biological physique, which makes people ask themselves the question 'Is she Chinese or Vietnamese?'. Metaphorically, what counts is not the mechanics of bio-engineering that grafts Chinese branches onto the trunk of the Yue tree that bear similar Vietnamese fruits, branches, leaves, flowers like other trees but the bio-genome (Charles Darwin. 1859). That is what made the Taic and Yue racially mixed Chu subjects, including Sinicized nationals of Yue descents as in the case of coercion of local Yue women to marry northwestern Qin infantrymen in Qin Empire in China South who later became subjects of the Han Empire, including those in Jiaozhi Prefecture in North Vietnam.

Vietnamese is a language that has populated all Sinitic elements on top of its common base of ancient aboriginal strata with some indigenous basic word remnants still in existence. In fact, Vietnamese etyma largely consist of a greater amount of Chinese loanwords in both Sino-Vietnamese and Sinitic-Vietnamese categories, a small number of the latter had actually evolved from ancient Yue roots which had also been shared by several Chinese dialects as well, e.g., those variants from Cantonese, Fukienese, Hainanese, etc., in China South (see illustrations in the succeeding sections after the next). However, it must be noted that the case of the Vietnamese development had gone through the 1000-year domination of Chinese rule had it totally transformed into a Sinitized language, literally, but not a creole or some other postulated 'hybrid' languages, such as Creole or Albanese of which vocabularies are totally comprised of loanwords from several other prominent languages with a few hundred of native words of its own left (Bloomfield. 1933).

It is interesting to note that some of the basic Yue-based words had already existed in ancient Annamese prior to their doublets finding their way back again into the Vietnamese fundamental stock, the second or the third time, by way of other routes, e.g., 'chuột' vs. 'tý' for 子 zi SV 'tử' (rat), 'dê' vs. 'mùi' 未 wèi SV 'vị' (goat), 'trâu' vs. 'sửu' 丑 chǒu SV 'xú' (buffallo), 'mèo' vs. 'mẹo' 卯 SV 'mão' (Cat), 'ngựa' 午 wǔ SV 'ngọ' (horse), 'heo' 亥 hài SV 'hợi' (pig), etc., including those postulated as of Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer languages of which the Khmer zodiac names of animals are attested from trade route from Annam in ancient times. In the same way, the whole process is similar to that of how Japanese words of modern Western concepts of the early 20th century such as 'dânchủ' 民主 mínzhǔ (democracy) or 'cộnghoà' 共和 gònghé (republic), that were built with Chinese materials, have found their way back into Chinese and then later the Vietnamese language.

Figure 6.4 - Is Vietnamese of Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer or Sino-Tibetan linuistic family?

James Campbell in Vietnamese Dialects once rediculed my ignorance of linguistics but he states it best that

"I originally included Vietnamese in this study/website because of the fact its phonological makeup is very similar to Chinese and, indeed, its tonal system matches the Chinese one. Originally I wrote at this site: "Vietnamese is neither a Chinese language nor related to Chinese (It is an Austroasiatic > Mon-Khmer language more closely related to Khmer/Cambodian). Besides having a very similar phonological system, and due to the heavy Chinese influence on the language, it also has a tone system that matches the Chinese one." However, after reading and conducting a bit more research, it appears that Vietnamese affiliation with Việt-Mương, Mon-Khmer, and Austroasiatic, may in fact be a faulty case."

[...] [Vietnamese] may not be considered a Sinitic language or one of the Chinese dialects, but the Kinh have a lot in common with the Chinese culture, and the language leaves little to doubt. I will not go into great detail about how this is claimed, as a great deal has been posted at some other websites (see below [for study by dchph, the author of this very paper]) and that is not the purpose of this site. However, one can see that Vietnamese shares many traits in common with Chinese: 60-70% Sinitic vocabulary, another 20% of vocabulary is substrata of proto-Sinitic vocabulary, much of the grammar and grammatical markers share similarities with Chinese, along with classifiers. One would find it very difficult to draw similar parallels between Chinese and other Mon-Khmer languages. It seems that after considering all of this, what is left that is Mon-Khmer is actually very little, and probably acquired over time through contact with bordering nations. For example, the numbers are of distinct Mon-Khmer origin, however, used in many compound words, Vietnamese uses instead Chinese roots (as is common in the other Sino-Xenic languages, Japanese and Korean)." (X)

Let's talk a bit more about the affiliation of the two countries in terms of political geography where nothern Vietnam's region once was a part of the Middle Kingdom before the 10th century. On the one hand, to write Vietnam's history of the early days as it was first written – such as the The ĐạiViệt Sửký Toànthư (Complete Annals of ĐạiViệt) in 1479, the official history of the Lê Dynasty, originally compiled by the court-appointed official Ngô Sĩ Liên, by the order of King Lê Thánh-Tông – historians normally referred to Chinese records for historical anecdotes of the place once called Giaochi (交趾 Jiaozhi), even all the national names – State, kings, places, people, etc – are called by Sino-Vietnamese translation such as vua "Hồngbàng", "Hùngvương", or "Andươngvương" to relate to the establishment of ancient state of ÂuLạc.(A). In search for an even more archaic period with those already existed folklores of which some legends could be attested also with earlier Chinese historical records, for instance, the legend of Vietnam's "Thánh Dóng" who fought against Yin invaders (1718 B.C.-1631 B.C.) (董)

Early Vietnam's history is made up for pieces of China's history. At the very least, they have been essential parts to what happened to Vietnam's prior to her independence in 939, on the other hand. Annals of ancient Vietnam was a part in China's history as Annam was never recognized as a sovereign state in any official China's history (See Si Maguang's Zizhi Tongjian in modern Chinese language, 72 volumes, by Bo Yang. 1983-93). Throughout the long Chinese colonial rule from 111 B.C .to 939 A.D. there emerged one short interval of an independent Vietnam ruled by the Early Lý Dynasty from 544 to 602 A.D. and ancient Vietnams was still considered as only a vassel state of China. Meanwhile, for the most part Annam was normally treated by China as its renegade prefecture even long after it became sovereignty; it simply dispeared in Chinese history. In effect, the ancient Vietnam had been considered as a prefecture of the Chinese empire until the Qing Dynasty late in the 19th century. By then its declining Manchurian government was forced to sign the Treaty of Tientsin (1885) with the French government to renounce its protectorate rights in Annam to France. It is only by then that Vietnam was called by name as another country in China's offical records.As a matter of fact, to compile specifically about the nation of "the Yue of the South", i.e., Việtnam, in continuation, Chinese history is indispensable in providing with records of all chronological phases of the develoment of the nation of Vietnam unless Vietnamese historians do not seek to connect the ancient Vietnam prior to her independence in 939 A.D., that is, 1,000 years long of "northern colonization period" (北屬時期) that was imposed on the region of Giaochi in the eastern part of today's North Vietnam starting in 218 B.C. under the rule of the First Emperor Qin Shihuang (秦始皇) as a prefecture of the Qin Empire until it became part of the larger Namviet Kingdom established and ruled by the Triệu Dynasty (207–111 B.C.). Ancient Vietnam continued to be a prefecture of the Middle Kingdom as Giaochau and Annam under the rule of the succeeding Han Dynasty until the end of the Tang Dynasty in 907 A.D. as the Middle Kingdom entered a turbulent period having been broken up into 10 states, which created favorable condition for the emergence of an independent Vietnam in 939 A.D.

History of ancient Annam had simply been "Annals of local events" (地方誌) of China. Throughout the colonial period under the Chinese rule, as sporadic uprisings and rebellions were always expected to be suppressed eventually; therefore, there was no recognition of any "constant resistance wars". Vietnamese historians, however, like to assume that Vietnam used to have her own written historical records and literary works which include the two declarations of independence of their ancestral "Southern Yue State" (NamViệt) (I) despite of the fact that they all were written in Chinese even after her independence.

Many Vietnamese scholars believe many Vietnam's historical records could not be found now because they were destroyed by constant resistance wars. They further imagine that when the Chinese aggressors left the country, they did not forget to bring home with them all available books from their old colonial Annam. As a matter of fact, Giaochi, i.e., aother name of China's prefecture of Annam, as previously mentioned, was never considered as an independent state in China's history; therefore, the Chinese colonialists had no neason to feel any threats and excuses to be prepared for a total evacuation from the Annamese colony, let alone having plan to bring back to their motherland all cultural artifacts and historical records for Annam was their homeland as many of them had been actually born and lived there for all their lives; the colony would be always there for their heirs to exploit. Specifically, all other greedy Chinese mandarins would never care much about cultural heritage but monetary valuables such as gold taels and precious germs and Chinese generals were busy securing their interests in their own soldiery stations as their estates. (V) Such supposition was highly probable for the reason that throughout the time span during the chaotic period immediately after the collapse of the Tang Dynasty in 907 as the whole union of Middle Kingdom was broken up into 7 major different states, with each having been ruled by different self-claimed emperors or kings overall for 72 years until 979.

As a matter of fact, before and after 939 back in the mainland those divided states had been ravaged in ferocious wars among warlord factions raging on while the Annam Prefecture, inside the Qinghaijun Military Zone (清海軍區) then, was the prosperous and safe haven usiness as normal, home away from home. Again, note that by then even though Annam had been a de facto sovereignty, Chinese rulers and their historians just treated it like a renegade prefecture, comparable to the picture of Taiwan or even Hong Kong at present time. It is understandable that, moreover, most of the Chinese colonialists and their family – of high officials appointed by the NanHan State's imperial court (南漢王國, 917-971, consisting of territories of today's China's provinces of Guangdong, Guangxi, Hainan, and the northeastern part of today's North Vietnam) which was then controlled and manipulated, interestingly, by eunuchs – in this case the stationed colonists would rather choose to remain in the Annam Prefecture than to return to the inner mainland up north as the state of NanHan show signs disintegration. Besides, for all high officials of the state in order to hold important governmental posts, they were supposed to be castrated, each one to become an eunuch among some 20,000 significant others. (Bo Yang, Vol. 72, p. 160. 1993)

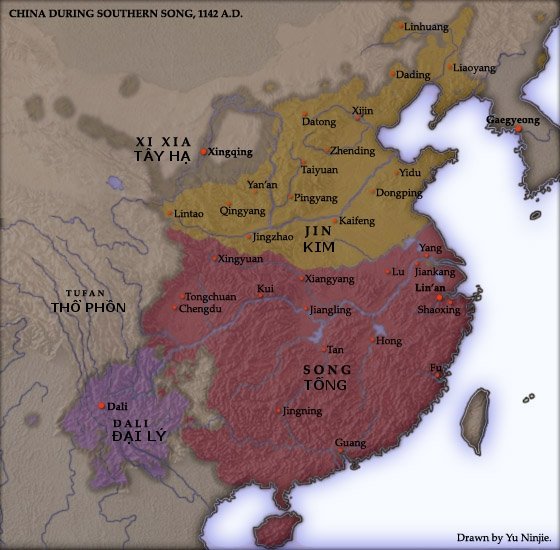

Figure 6.5 – Fourth Chinese domination of Vietnam

China's province of Zhejiang around the 940s was the origin of the Chinese Hồ/Hú family from which Hồ Dynasty founder in Vietnam, Emperor Hồ Quý Ly came from. The Ming invasion had been preceded by a campaign against Chinese culture during the combined 7-year reigns of the two emperors of the Hồ dynasty, Hồ Quý Ly in 1400 and his second son, Hồ Hán Thương, from 1400 to 1407. During these 7 years the two Hồ emperors asserted Vietnamese culture and language and banned use of Chinese language and writing in government. When the Ming invaded the cultural campaign was reversed; all classical Vietnamese printing blocks, books and materials relating to Vietnam were suppressed. For this reason almost no vernacular chữ nôm texts survive from before the Ming invasion. Various ancient sites such as pagoda Bao Minh were looted and destroyed. The Ming dynasty applied various Sinicization policies to spread more Chinese culture in the occupied nation.

Source: wikipedia.org

Linguistically, in order to understand the becoming of the Vietnamese language it should be put under the historical perspective in terms of such dynastic events. The ancient Annam, as a colony of China, was a place for the Chinese colonists to exploit natural resource at the expense of the local people. The commonest colonial consequences were the displacement of the native from their homestead and disruption of their economic activities, and in this case, they became minorities in their own ancestral land. The invaders who governed dictated what they saw fit. Their colonization policy was enforced by heavy-handed oppression at times, apparently demonstrated in cutural resistance clashes as well. With the presence of those had solid grips of power, several factors had detrimentally influenced the developmental course of the ancient Vietnamese language because that was determined by the rulers what the people in the colony would learn to speak. Examples like that were commonplace in the world's history. In Annam, while it had been already under strong Chinese linguistic influence for the last 1,600 years until it fell again into the dark 20-year period of the Chinese occupation again in 1407 as the Ming invaders implemented their annihilative policy to wipe out the local culture, including any extant 'Nôm' literary works. For the next 500 years after winning the resistance war against the Ming in 1427, ironically, the kings of the Annam's post-Lê Dynasty would but return to the same centuries-old course of development. Academically, while inflexible use of the formal classic Chinese Wenyanwen (文言文) adopted by the ruling monarchy throughout the national history, there existed Sino-centric scholars with their willingness to adopt Chinese lingo wholeheartedly, from literary to dialectal and coloquial speeches within circles of the officials in the Annam's court. Except for Vietnam's annals, there went hand in hand with look-down attitude toward local academic works. Such unpatriotic craze of Chinese scholarship lasted all the way until the first 2 decades of the 20th century when the focus turned to other direction that went after the newly introduced Western culture brought in by the French colonists, that is, introduction of the French language in the national examinations – in concurrence with the classic Chinese language – and the newly adopted national Vietnamese romanized orthography called 'Quốcngữ' was first implemented in the nation in 1909, then those of 1910, 1912, and thereafter subsequently. (Nguyễn Thị Chân-Quỳnh. 1995. pp. 16-46, 104-110).

Obsession of the Chinese culture was widespread among the common mass in the countryside as well. Nguyễn Thị Chân-Quỳnh (ibid. pp. 110-111) quoted Nguyễn Văn Xuân (1970) in his Phong-trào Duy-tân ('Reform movement for modernaization', Saigon: Lábối publisher, 1970) that, surprisingly, even villagers up until 1970 still put paper written with Chinese scripts called "ChữNho" (儒字) in the sacred places around the house while newspapers with printed material with Latin alphabets could be made used of as toilet tissues. Now that contemporary scholars have made a 360-degree turn with heated nationalism that smears neutrality in academic realm. The damages have been done, though. Such an attiiude has been looked down by today's nationalists and been seen as a disgrace to the nation.

In quest of finding Chinese etyma that show cognates with Vietnamese basic words from the same source, it is recommened that historical linguists, especially local Vietnamese scholars, should try to bring back legitimate scholarship by means of making use of Chinese literary works and dictionaries such as Guangyun (廣韻) and Kangxi Zidian (康熙字典) or even latest work by Western academic in surveys on SIno-Tibetan and Old Chinese historical lingistics; otherwise, we will never be able to comprehend why there exist vestiges of northern dominant Chinese dialects in modern Vietnamese, that incudes the basic realm. As a matter of fact, many Vietnamese etyma can be identified as of the northern colloquial expressions and vernacular mandarin were supposedly spoken only by the general public living inside the Middle Kingdom but somehow also found in spoken Vietnamese, which indicates its pupularity that was spread to the general Vietnamese public as well, for example, 'mainầy' 明兒 míngr (tomorrow), 'lúcnào' 牢牢 láoláo (all the times), 'luônluôn' 老老 láoláo (always), 'khôngphảisao?' 可不是 kěbùshì (isn't it so?), 受不了了 Shòu bù liăo le! (Chịu khôngnổi rồ!), etc. Those forms of expressions are common usages in the official northern dialect. Historically, most Chinese rulers of the Middle Kingdom were northerners, including those of Altaic Turko-Mongol origin, which could be seen through the fact that their capitals mostly built in the northern region of the mainland of China, including the Ming's imperial palace, which had been initially located in Nanjing (南京) in the lower Yangtse Basin and then later was moved to today's current Beijing (北京) location despite of its extreme hash weather elements over there, including dust storms from the Gorbi desert in the north that have caused desertization by movable sand dunes.

How such Vietnamese and northern Chinese colloqiual forms have been affiliated might originate from racial entanglements that occurred throughout the colonial period. We could imagine that with incessant flows of Chinese immigrants who kept pouring in to the Annam prefecture since 111 B.C. and the trend continued on well beyond the period of Chinese colonialization with aforementioned northern Chinese dialectal speakers from China such as officials and infantrymen, along with their family members, who were stationed in the Annamese land and many of them eventually intermarried with the local people.

The fact that the Koreans and Japanese could not absolutely be identified with the Chinese still currently shows as those people of Chinese ethnicity living in South Korea and Japan for many generations remain aliens. Even though Vietnam survived the longest history of Chinese dominion, the process of Sinicization had put a heavy toll and left a permanent Sinitic mark on her people and their language. In comparison, unlike the other East Asia's Sino-xenic countries such as the two Koreas and Japan who uniquely display their own national identities, dispite of the fact that the northern Chinese consist no less Altaic-origin people than the racial ratio of the Yue to the northerners.

Ethnically, Vietnam's 84 percent of her nationals are of the Kinh majority, who are also known as Vietnamese ethnicity, supposedly their having a mixture of early ancestral Yue natives who had inhabited a wide-spread area stretching out from Lake Dongtinghu located in Hunan Province in China South to today's North Vietnam's region, including the lately acquired territory in the southeastern area for of the ancient Nanzhao Kingdom (南詔 738-902) – and subsequently of Dali State (大理國 937–1253 ) located in south of today's China's Yunnan Province – where Vietnam's present northwestern area is with a large number of Daic ethnic concentration. The Kinh populace have, in other word, evolved from racial admixture of Yue-Han resettlers who emigrated from the southerrn region of China with those indigenous people living further in the south since the Han Dynaty. The remaning 16 percent of the population consists of other designated 54 ethnic minority groups inhabiting in Vietnam's mountainous region up north stretching southward to the western plateau running from north to south where those Mon-Khmer and Cham minorities have been living in the eastern coastal lowland stretches that were seized from the two former kingdoms of Champa and Khmer in a much later development starting from the 12th century to the early 20th century. Those ethnic groups of Mon-Khmer origin were also known as montagnards while the Cham minority were descended from those subjects of the bygone Champa Kingdom who had survived the earlier annihilative slaughter in the 18th century for their uprising against the Vietnamese usurpation committed by King Mingmang of the last Nguyen Dynasty.

Figure 6.6 – Map of the Dali State in 1142

(Source: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/vi/d/d5/China_11b.jpg)

Anthropologically, with respect to the Chinese and Vietnamese racial affiliation one would be able to distinguish those Han resettlers in ancient times (who constituted a portion of the early Kinh populace in terms of their mixture with the aborigines) from those contemporary latecomers of Chinese immigrants as late as after the end of the World War II who followed the foosteps of Generalissimo Chiang Kai-Shek's troops to come to Vietnam disarm the Japanese surrender. Both former and latter Chinese immigrants lived mostly in the lowland and the coastal cities and townships, e.g., numerous Chinese Hananese and Fukienese ethnic groups living in Huế, Đànnẵng, Faifo (Hộian - 會安), Tamkỳ, Tamquan, Bồngsơn, Quynhơn, Tuyhoà, etc., who have made up the Chinese ethnic group officially called the Hoa (華) minority of around 1 million people whose ancestors were forced to adopt the Vietnamese citizenship by the southern government during the 1960s. All in all they gradually become fully intergrated members of the Kinh majority over the years. For those early Chinese resettlers – such as thousands of those refugees coming in by boats after the Ming Dynasty in the China's mainland fell into the hands of the northern Manchurians – they were credited for their contribution in development of new towns in 6 newly established southernmost provinces, especially Hàtiên, Bạcliêu, or even Sàigòn (西岸 Xī'àn), which historically belonged to the ancient Khmer Kingdom before the mainstream Kinh people moved in by the late 18th century.

More proofs can be found in a notable recent development in the transformation of the children of early Chinese immigrants to have become members of the Kinh majority who were no longer counted as Chinese in the official census are descendants of many Chinese-Vietnamese who were still left behind from the exodus of the Chinese ethnic groups who got out of the country by boats in 1979 right before the imminent Sino-Vietnamese border war started and the waves of boatpeople continued on until 1996 with approximatey 400,000 Chinese-Vietnamese refugees plus who fled Vietnam were later resettled in the US, Canada, and many other Western countries. (H) Let us take other samples on the ration of Chinese-ethnic populace that made up the Kinh majority with many of their forefathers such as King Hồ Quý-Ly or Governor Phan Thanh-Giản, along with with many other unsung heroes and common people alike in the general population of those millennials, a sizable portion of the Hoa minority, have become famous performance artists and persona in showbiz in contemporary Vietnam, such as Trấn Thành, Đàm Vĩnh-Hưng, Quách Thành-Danh, etc., not to mention all other personages in the political arena. It is so enumerated because the ratio of renown artists and the common populace is a fractional percentage in the overall population, say, one in a million, which demonstrates the magnitudes on becoming Vietnamese among descents of Chinese immigrants in Vietnam have been in remarkable droves.

As a matter of fact, the Vietnamese Kinh people, historically, were descents of early waves of Chinese immigrants followed the footsteps of the Han's invaders who had occupied and established their rule in the ancient Annamese land since 111 B.C. throughout the period that followed for at least 1000 years later. The Chinese immigrants from the north kept coming, resettled, and intermarried with local wives. They and their offsprings, as a result, mostly constituted an integral part of the already established "Kinh ethnicity" (京族) as previously mentioned. The term "Kinh" originally was used to indicate those "metropolitans" who resided in large townships around the Red River Basin and in the lowland along the coastal areas as the country expanded further to the south. No need to say, it is in those places where the Han colonialists had first built barracks to station their troops and residences to house their administrative officials. Many of them stayed over and made their homestead in the ancient Annam prefecture and never returned home, especially, when the Tang Empire totally disintegrated in 907.

The key word here is "millennium". As history has it, events that shaped up Vietnam from China's bondage are measured by units of 1,000 years each. After the country's independence, Annam repeated the process of colonization that China had done to the ancient Annam for 1,000 years before. For the next 1,000 years, in fact, just like those earlier Chinese who colonized the ancient Annam, the later Annamese invaders took their turn to play the role of expansionists. After 939 A.D. as people of the newly established sovereign state of Annam advanced further to the south, they encroached and annexed its adjacent territories hold by weakened neighbors through wars and bold resettlement. Over time and along the way southwards, they intermarried with the local Chamic and Khmer people. Those local people of the two lost kingdoms in effect mixed with the Annamese resettlers to have given rise to the latest new mixture of the late Annamese generations. As a result, the racial integration and language development continued on with a new twist of the Chamic and Khmer elements in the later period of development that made a more lax pronunciation by speakers of the whole distictive class of Southern Vietnamese that have been formed in the last 300 to 500 years than the ancient 2,200 year-old northeners, anthropologically. As a matter of fact, by the early 18th century the late Annamese resettlers had reached the region of today's Rạchgiá Province and mixed not only with those Khmer people but also with descendants of those earlier Chinese refugees led by Marshall Mạc Cửu and his people fleeing the Manchurian rule in China after the fall of the Ming Dynasty who had first been allowed to resettle there by the Nguyễn monarchs.

The newly racially mixed offsprings emerged and they would pose no distinction with the Kinh majority in terms of racial mix for their physical appearance look alike probably due to the similarity of the harshly warm climate of equatorial region where they were born. In sum, the Vietnam nationals as we have seen all over places in modern Vietnam, altogether the 6 main ethnic stocks have made up the Kinh majority, i.e., the Taic, the Yue, the Chinese, the Daic, the Chamic, and the Khmer people. Their populace plus those who were later identified as of Chamic ethnicity in the official 2010 census were made up only a small portion of the Kinh population due to historical events by the end of the 19th century – as the population of the Annam reached to 20 million – for the reason that, firstly, there occurred ethnic lynching committed during the reign of King Minh Mạng against the Chamic minority for their past cooperation with the opposing Tâysơn forces and, secondly, descendants of those native minority of the lost Champa had to claim themselves as of the Kinh ethnicity in order to avoid indiscriminate mistreatment and execution by the late monarchs of the Nguyễn Dynasty. So were those Khmer ethnic groups in the south after portions of their ancient kingdom's territory were annexed into the southern part of today's Vietnam.

While Cham or Khmer heritage has been largely acclaimed with prestigious cultural artifacts and colossus monuments, many Vietnamese academics have missed the point mainly more on the Chinese racial factor. It is probably that the term "Chinese" has bothered them all along just like what we already discussed about nationalism and politics in the previous chapter. It is understandable because what else would one expect to see could have emerged from an ancient prefecture of the Middle Kingdom for 1000 years then? Compare the case of past Vietnam with many other former colonies in the world, such as Ireland vs. England, Mexico vs. Spain, or in China where Canton's or Amoy's indigenous entitties, i.e., aboriginal Yue people in ancient region's where today's Guangdong and Fujian provinces located, have been totally assimilated into the Han Chinese mainstream, Vietnam experienced the same fate that it would fail to resist and subdue increasing pressure of assimilation after hundreds of years under the domination of a much more powerful country than itself. It is a plain and simple cognizance. It is not hard for even a novice to grasp the core matter with the reinstatement as such.

Figure 6.7 – Bảngiốc Waterfall over the river

Artistic render of the Taic-Yue-Chin-Chamic-Khmer cascades of the modern Vietnamese language.

(Source: modified from a photo of Bangioc Waterfall)

To be easier on the brain similar to those of artists who could visualize strings of data, here is another way to depict of the whole rationalization as discussed above.

Let's paint a picture of an imaginary Vietnamese national landcape with infusion of water-colored ink with the dark spot on top and the lightest one down below. Analogously, the overall process looks like multi-tiered waterfall with the current flow that streams down and inundates a pool at the bottom cascade. Imagine the cascade underneath the top one stood for the early Chinese – as the Han Empire's subjects – who were largely made up with all the subjects in the ancient states of Qin, Chu, Wu, Yue, etc., of which their offsprings had been descended from the Yue root as well. It is the Taic, or proto-Daic (先傣) and pre-Yue populace of the Chu State (楚國 c. 1030 B.C. - 223 B.C.) – who were called "Malay" people by the Vietnamese author Bình Nguyên Lộc (Nguồn-gốc Mãlai của Dân-tộc Việt-nam or 'The Malay origin of the Vietnamese'. 1972) whose arguments were supported by the early 20th century academics (Phan Hữu Dật, 1993) or the Shan-Taic by Lacouperie (1887) as opposed to 'Taic' or 'proto-Daic' and 'pre-Yue' as mentioned herein – who were represented by the cascade that towers at the peak as the source pouring downward until the muddy water body – symbolizing foreign objects that made up the early proto-Chinese normadic horsemen who had conquered the ancient mainland of pre-China – was totally infused with other elements at the bottom. Submerging in the lightly colored stream further down below are current that blended all foreign substances all the way down from the top – that is, the racially-mixed populace of both the Han and Yue people – and pick up other elements – e.g., Cham and Khmer, etc. – along the way before reaching to the Annamese pool. What is inside it analogously made up the ancestors of ancient Vietnamese and other southern racially-mixed populace in region of China South who were descended from the Yue people as well. Altogether, they integrated well into the Vietnamese racial composition.

Such a theory as discussed above is construed with Chinese historical records. Many Vietnamese nationalists, nevertheless, might find it hard to accept such Sino-centric view because it is inundated with Sinitic elements per se on what they already considered as of "pure" Vietnamese entities, racially and linguistically, pertaining to their respective origin (subjecting to how we define it). On discussing about history of a language and its speakers, one has to choose between non-fictional and legendary stories to start with. If one chooses to go with history, they (T) must understand that the composition of the Vietnam's "Kinh" people have been an inevitable result of racial mixture of the native Yue people and the so-called Han people over time, a product of China's continually encroaching the southern region that pushed the Yue refugees to flee further to the south. Many ethnic groups in Northern Vietnam indicated the trend went on until at least 100 years ago, of which the whole process took place in the very similar fashion to what made up the populace of the Han Empire after it had conquered the NanYue Kingdom in 111 B.C.

There existed, however, no such entity called the "Chinese race" but only the Chinese culture and the people who adopt it. With respect to the Chinese people, before or after the Han Dynasty, they are actually of racially mixed stock, having emerged from the unified empire first established by the First Emperor Qin Shihuang of the Qin Dynasty which establised what now known as "China". The Qin Empire initially encompassed (a) all the subjects of other 6 states (whose forefathers were unlikely of the same ancestors with those of the Qin State in the northwest region in Shaanxi) that it had previously conquered and added to the racial stock of (b) its original populace who were descended from an ancestral line passed down by those proto-Tibetan normadic horsemen and (c) those ancient northern tribes of non-Taic origin from the earlier periods of the Shang and Xia (ancestors of the Altaic line and its Turkish descendants in the northeast region of Shanxi and Shandong, China North), plus (d) all the people in those earlier states which had paid tributes to the feudal Western Zhou's kings whose earliest ancestor came from the Hunan, China South. As the Qin Empire conquered and expanded further to the south, the Chinese people emerged from the latter groups having mixed with indigenous Yue inhabitants in China South. Its population were multiplied with more indigenous Yue tribes as their territories were incorporated into the geo-political map of an entity being known as the Middle Kingdom (中國).

In a succeding course of events, nevertherless, the short-lived Qin Dynasty finally collapsed and the contention with the defiantly reborn Chu State to take over the whole empire was finally won by the empowered Han's first king, Liu Bang, and his generals, notably all having been the old Chu subjects who were descendants from the same Taic ancestors of the Yue.Figure 6.8 – Map of the Zhou Dynasty

(Source: http://web.archive.org/web/http://www.art-virtue.com/history/shang-zhou/shang-zhou.htm)

The Han Empire, a continuation of the unified Middle Kingdom, had its territory expanded and populated with a great number of the subjects of all other ancient states. Racially and linguistically, the Han's elements grew on top of what was already composed of those populace of the Chu State and then later added up with those Yue components from the later NamViet Kingdom. Thenceforth there emerged the people called 'Han', including those later acquired territories in today's of Guangdong and Guangxi provinces. In other words, they consisted of all people living within the Han Empire since then would be called the Han people (just like an Amercian born in the US, analogously). In other word, the formation of the Han Empire's populace was the result of the mixture of those original subjects – who previously had already made up a part of the multi-state populace of the Eastern Zhou Dynasty – of the subjects from the fall of the Qin Empire and were blended with the people north of the Yangtze River and the Yue people in the China South region.

It was not of any secret that the Han soldiers were those of the wretched poorest who had no means of making a living so they join the army. In Chinese, there is an old saying that goes, "好男不當兵, 好鐵不打釘" (Good men don't join the army; good iron is not for making mails.) The idiom is so cited here just to emphasize the fact that out of hundreds of thousands of Chinese solders who went to colonize ancient Annam only a few would be able to make it back home. As a members of "the elite ruling class", their life would better off resettling in the fertile land of Annam.

Since 111 B.C. after the Han Empire had annexed the whole NamViet Kingdom into their newly unified Middle Kingdom, the racially-mixed Han people from China South kept infiltrating continuously into the southeastern region of the empire, that is, the northeastern part of today's Vietnam, where the newly annexed Giaochỉ prefecture was established. Of the first waves of the Han colonists with their infantrymen marched southward, many of them originally of BáchViệt (百越 BaiYue) origin in the China South as forementioned were displaced from their ancient habitat in the northern region – just south of the Yangtze River (楊子江) in today's Hubei and Hunan provinces – to other faraway places in Vietnam's Red River Basin (Đồngbằng Sông Hồng) and many of them resettled there, permanently, mostly because they had no means to return home.

At the same time, following the long-marched Han soldiers were those exiled officials and their family, and other refugees fleeing ravages of wars and hunger, as well. Altogether they moved in en masse and finally all made their homestead in their newly occupied territory which was later known as 'Annam Đôhộphủ' (安南督護府 'Southern Pacification Protectorate Prefecture') until the end of the Tang Dynasty. Many of them even encroached further into lower level cultivated land of southeastern basin in Vinhphuc and Hoabinh provinces of today's Vietnam, resettled there, and never returned home. Altogether, 1,000 years after that colonial period, they made up the larger part of the Kinh mojority population of the newly independent Annam.

Figure 6.9 – Map of the Han Dynasty

Map of the Han Dynasty

(Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Han_Dynasty)

As a matter of fact, 99 percent of the Kinh people today bear Chinese family surnames. Note that the social intercourse was similar to events of racial integration process during the short-lived Qin Dynasty that carried out an imperial decree that coerced more than 30,000 local women to marry their soldiers. We already discussed much of this matter in the previous chapter on politics. In short, to say differently, it is because either home-groomed scholars mostly keep themselves in the line of politically-correct code or they are among those Vietnamese people who misplace their national pride.

To understand the matter better under the perspective of anthropology, one can compare what was postulated on the origin of the Vietnamese people with some other similar development of those countries that have taken on the same path in establishing a new multi-racial nation, regardless of specific ethnicity origin. That was how the Annamese entity began to emerge some 2,200 years ago. For example, contemporary Asian history has witnessed the three consecutive prime ministers of Singapore and all Taiwan's presidents, like their fellow countrymen, are all of China's mainland's origin in terms of where their ancestors come from, specifically Fujian Province, and they take pride in themselves as Singaporean and Taiwanese, respectively, in such a proud manner that goes hand in hand with one's national identity. Read the Figure 6.10 below and you will see the parallel development of both Vietnam and Taiwan. What happened to Vietnam 2 millennia ago is currently happening in Taiwan in our contemporary era. Of course when making an anology, one can eliminate modern technology factors, e.g., transportation, communication, linguistic orthography, etc., out of the equation, so to speak, because the modern factor, obviously, retain the consistency of standard ponunciation of a language and prevent it from changing.

Figure 6.10 – Taiwanese Identity

Of the 23 million people in Taiwan, 98% are descendants of ethnic Han Chinese immigrants who migrated from China from the 17th to the 20th century. Of these, around 70% are descended from immigrants from Fujian and identify themselves as Hoklo whilst 15% are Hakka from Guangdong (Canton) and also Fujian. The ancestors of these people were laborers that crossed the Taiwan Strait to work on plantations for the Dutch. It is believed that these male laborers married local aborigine women, creating a new ethnic group of mixed Chinese and aborigine people. It is these descendants who identify themselves as Taiwanese and increasingly reject their identity as Chinese. The reason for this lies to a great extent with the authoritarian rule of the foreign Kuomintang (KMT) which fled mainland China during the Chinese Civil War and set up government in Taiwan. There was martial law that lasted four decades and was discriminatory against the existing inhabitants of Taiwan. Mandarin, a foreign language, was imposed as the national language (國語) and all other languages were made illegal. The harsh rule over Taiwan was lifted in 1988 and began a new era in Taiwanese history when Lee Tenghui, a Taiwanese, became president. The first transition of power from the China-centric KMT occurred in 2000 when Taiwanese Chen Shui-bian of the Democratic Progressive Party won the presidential elections. He made efforts to push for Taiwan independence with statements that there are two nations across the Taiwan Strait; a push for plebiscite on independence; and the abolishment of the National Unification Council. Taiwanese opinion on independence is split between the northern and southern half of Taiwan which interestingly also divides the "mainlander" (外省人) in the north from the "Taiwanese" (本省人) in the south.

Source: http://www.taiwandna.com

Think of projected total of all children born to more than one hundred eighty thousand Vietnamese women (as of 2018) married to those local husbands in Taiwan – except for those new arrivals in 1949, most of whom are original descendants of fully Sinicized Fukienese {X2Y3Z4H} (交) immigrants from the mainland of China since the 17th century – from the last 30 or more years. The population of the offsproing from their union as of now could probably have surpassed the total population of about 900,000 people in ancient Annam as recorded in the Han's population census of the Giaochâu (交州 Jiaozhou) prefecture 2,000 years ago. The racial ratio and balance of the two racial compositions could have been at the same level except that Chinese descents in Annam are called 'Annamites' while the other 'Taiwanese', each speaking diferent a Sinicized version of their own language, including the proportion of each respective aboriginals. In the context that it does not matter much what their actual country of origin is; it is where their birthplace that counts. The Taiwanese shoul include both the "mainlander" (外省人) and the "Taiwanese" (本省人) withstanding they all are holding tight on the precious status-quo of sovereignty, short of the last step in declaring independence for Taiwan as a new nation just like Vietnam. In fact, regardless of the Chinese-origin of many Vietnamese, they take the pride in their long history fighting against mostly Chinese invaders, especially their incredulous victories of having unprecedentedly defeated the Mongols 3 times in the 13th century (M) who conquered and ruled China for nearly 100 years. They have sacrified a great deal to defend and keep the foreign forces at bay for the last 1,080 years one generation after another. Except for Vietnam's aggressive expansionism on the historical acquisition of stretches of land south of the nation, one by one, that used to belong to the now extinct kingdoms of the whole Champa and, partly, of the Khmer, her sovereignty still hold as a model that both the Tibetan and Uyghur people all are longing for their respective homehand that is still under the control of the Chinese . That is so said because they are undergoing what ancient Vietnam had gone through hundreds of years ago before the 10th century.

For a linguist, sole elaboration on the political, cultural, and historical aspects of a language under survey is sufficient if the matters under discussion are considered as irrelevant to one another like those of Mon-Khmer and Vietnamese for the reason that history of their development had been independent of each other until the last 350 years. What previously belonged to the Khmer then became part of Vietnmese and vice versa. The point is that is used to be the cases between the Vietnamese and Chinese and the Taiwanese and Chinese, per se. In the field of Sinitic-Vietnamese study it is more of the norm than not, one still needs a more comprehensive approach to cover all of the above plus other anthropological elements because they all are relevant and interrelated intimately; otherwise, one could not explain the cognateness of unrefined words currently existing in Chinese and Vietnamese, such as private human reproductive organs and sexual acts such as 'cu', 'cặt' 龜 guī, 'hĩm', 'lồn' 隂 yīn, 'bề' 嫖 piáo, 'đụ', 'đéo' 屌 diăo (SV điệu, Cant. diu2, Hakka diau3), etc., not to mention all other 'refined' words, e.g., 'ânái' 恩愛 ēn'ài, 'giaohợp' 交合 jiāohé, 'giaocấu' 交媾 jiāogòu, are of the same roots. Those similarities are the underlined genomes that gave rise to unique peculiarities that exist only in genetically affiliated languages, so to speak.

Their linguistic commonalities are characterized in all different 'Chinese' dialects and sub-dialectal variants, exposing intrinsically shared features that could not be found in other languages of different linguistic family, say, Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer, to say the least. It is such uniqueness that also masks the true appearance of the same etyma since they possess so much likeness that could only be either used to posit as of the same root or discarded outright as loanwords because of their closeness. For example, 'đường' 糖 táng (sugar) vs. 'đàng' or 'đường' 唐 táng (path), both Chinese and Vietnamese forms are of the same origin, with the former as originated from a Yue root (because Guangxi region historically has been a place to plant sugarcanes since the ancient times) and the latter, /dang2/, highly likely from Middle Chinese, respectively. You will see more of this kind of cognates later when we extend them further, each as component of dissyllabic and 'bisyllabic' (reduplicative) words as in "đáiđường" and "tiểuđường" 糖尿 tángniào (diabetic) where 尿 niào (SV niệu) are wholly cognate to both "tiểu" and "đái" and 尿尿 niàoniào can be postulated for "điđái" or baby 'pee pee' or '(go to) urinate' and compound ones such as 'đáiđường' (to pee on the street in public view) 'điỉa' 屙尿 Cant. /o5niu2/ (go to poop).