Vietnamese Chinese

What Makes Chinese so Vietnamese?

An Introduction to Sinitic-Vietnamese Studies

(Ýthức mới về nguồngốc tiếngViệt)

DRAFT

Table of Contents

dchph

Chapter III [continued]

B) On the one-size-fits-all conspiracy

The author has long suspected that the Austroasiatic hypothesis was initiated by those who were not proficient in both Vietnamese and Chinese and their speakers' national history. Western neo-theorists just wanted to make shortcuts by means of manipulating data in such a way that their hypothesis could negate all other preceding theories by using power of supposedly popular Western research methodologies especiall in the period after the Industrial Revolution in the 18th century. For such matter, the Western academic world had known little of Chinese up until the beginning of the 17th century (Knud Lunbæk. 1986. Ibid.) The author's suspicion is based on its rigidity of old data, inflexibility of formulated presentation, mispellings of words, generalization from small samples, and repetition of the likes.

The explanation for such phenomenon would be a premise for more like the metaphor of chicken or egg first genesis in nature, but guessing whether the hatched fowl will come out its shell a chicken, hen, rooster, or cock. For example, in Ancient Chinese we can say with certainty that 土 tǔ (soil) had come before 地 dì (land) or 口 kǒu (opening) prior to 吻 wěn (mouth), but could any Sinotibetan-specialists tell which one — Chinese or "Yue" — of the following Vietnamese descendant equivalent 'đất' vs. 土 tǔ (soil) or 'cửa' vs. 口 kǒu and 'mồm' vs. 吻 wěn (mouth) had come first originally in ancientforms? Who knows if those cognates might not be related at all in Chinese itself in the end as the language evolved, for example, 吻 wěn => 'hôn' (kiss). If our Sino-Tibetan specialists could not say for sure, what makes the Austroasiatic theorists to be so affirmative about which came first then? That is why we acknowledge that each theory on genetic linguistic affiliation is still one of hypotheses in our time, let alone the Austroasitic theory clearly having no historical records to back them up.

Let's relax and play with words a bit first for the purpose of helping visualize the whole picture of the matter, taxonomically. Metaphorically, the Mon-Khmer theory is of a few 'specimen fish' in a larger basket whether be it an Austroasiatic, Yue, Taic, or Sino-Tibetan species where the last ones are netted notably in much larger fry batch than the rest — with the early Chinese written records logged in for each catch as seen with carvings on oracle bones, devine turtle's shells as well as bronze tripod caldrons, etc., within our purport timeframe, excluding nonsense mumble in mystic Pali or Sanskrit prayers in the air. — Conspicuously, the Tibetans took lengthened notes on them. As the author sees it, along side of the "Bod" (Tibetan) languages, there had existed first the Taic, then came the Daic and the Yue split of which each line of offsprings is on par with the Sino-Tibetan family giving birth to its Sinitic descents that could be grouped side by side with the Tibetan and the Yue elements. Perspectively the contemporary Austroasiatic hypothesis captured all of the above and positioned itself in its own class as an antithesis to counter the Sino-Tibetan one on segments of Annamese. While the ancient Taic gave birth to the Yue — that brought up our contemporary Sinitic Vietnamese — and Austroasiatic languages, for the latter hypothesis, the fairly new Western view dressed it under the outfit other than that of the Yue theory — that of 越 /Jyet/ to be exact as it, was transcribed under various homonymous characters from Chinese annals. As we are talking about the southern migratory movement — hence the Southern Yue — from the China South to the Indo-Chinese peninsula, the Sino-Tibetan theory, etymologically, is plausible to explain the cognacy of more than 400 fundamental words in both Vietnamese and Chinese as cited in this survey; however, going the Sino-Tibetan route means to take pain to dig under mountains of Chinese historical records mostly written in archaic forms with classical styles, which is chosen to support our theorization. In any case, this is not a matter of favoring larger fry catches over rare specimen fish for the reason that one cannot deny the existence of many basic Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer cognate anchovys, scarce yet importantly fundamental, which are found present in the neighboring Mon-Khmer waters. Having postulated the affiliation with the faraway Munda in coastal India to the east, the Austroasiatic navigators set sails to that direction and they netted a small catch with a few etyma affiliated with Munda in India (see Chapter 8 on the Mon-Khmer association.) All that said, we could confidently assume that there firstly had existed the Yue entities and then came whatever next no matter what.

The Austroasiatic hypothesis, as a matter of fact, could be best used as patch works to fill in all possible cracks — where the Sinitic elements still stayed hidden and unnoticed — in between linguistic pockets scattered intercontinentally within the timeframe of approximately 6,000 ~ 10,000 years ago (the same estimate might be reached with the least percentage of basic cognates with glottochronology calculation.) It is understandable to see Indian elements in the Khmer and Chamic languages in ancient forms of Sanskrit or Pali origin words as they used to be under strong influence of Buddhism and Hinduism, respectively, but they appear to be alien in Vietnamese except for what they sound in common Buddhist prayers such as 'MôPhật', a shortened form of 'Nammô AdiđàPhật' (Namo Amitabha) that is assume to convey a much localized context.

As we have seen so far is the 'status quo' that reflects an end result following a series of hypotheses that either seek to (1) nullify the current existing theories of Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer or Sino-Tibetan origin from opposite viewpoints, say, China's official institutions group Cantonese, being a language of the Yue, as descended from the Sino-Tibetan family based on Sinic etyma in their vocabulary stock, or (2) build afresh another theory based on the same hypothetical foundation while taking advantage of progress in new methodologies, for instance, in addtion to similar approaches taken by the Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer hypothesis itself, there came the 'Austro-Thai' initiated by Benedict (1975). Countering all previously existing theories, the Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer theorists built theirs on the premise that there had first existed the Mon-Khmer aborigines — instead of Yue-Daic resettlers — themselves physically in the Red River's Delta before the other migrants moved in. Arrivals of the later immigrants mixed with all earlier inhabitants there had given birth to their offsprings who spread out across Southeast Asia. Only then the Tai-Kadai speakers from the southwestern region — present Lower Laos — and later the racially-mixed Sinitic-Yue all from the China South moved in waves after waves throughout the Han colonial period. It was then from that of the Mon-Khmer homebase, subsequently, there appeared the modern designated "Austroasiatic" linguistic family that fanned out therefrom across the Indo-Chinese peninsula to both the northern and western directions of which Mon-Khmer speakers encroached and introduced basic words, indisputably, to newcomers who spoke earlier form of the Vietnamese language by the whole local population thereof. Even though many words were later proved to be cognate to those modern Cambodian etyma, the concensus was still reached by Austroasiatic theorists that the Vietnamese language origin descended from the Mon-Khmer languages. (see Nguyen Ngoc San. 1993. Ibid.) Genetically speaking, the Vietnamese genome maps that have been studied by Vietnam's DNA institution recently show results that, with trustworthy proofs, the Vietnamese, Thai, Daic, Yao, mong, Mon, Khmer, southern Chinese... all share the similar genetic forms.

People tend to either take what they already believe and follow the crowd. It is, therefore, simpler and straightforward for newcomers not to hesitate taking their initial steps to follow such path, trendy and fashionable as well, that is, acceptance of their classification of Vietnamese into the Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer family, which is one of the largest theories on genetic linguistic affiliation. Linguistically, postulates of those designated Austroasiatic languages — as having evolved from a common Taic-Yue linguistic form that also gave birth to daughter languages of the Yue spoken by ethnic groups living around the southern region of China — could be based on affirmation of those Taic-Daic languages in China South. The same Taic-Yue linguistic family could be extended even further to other linguistic divisions such as Tai-Kadai, Austronesian, Polynesian, etc., all being considered as breakdowns of the Taic linguistic family.

To see how the Austroasiatic theorists approached the Vietnamese language in the beginning with Indo-European linguistic methodologies to build up their new Mon-Khmer hypothesis as presented above, it appears that it did not need to tax much of their gray matter to establish new theory and play the leading role of world's linguists (see A. Meillet's & Marcel Cohen's Les Langues du Monde. 1952.) Let us equip ourselves with Western tools to tackle an imaginary linguistic case in the Amazon jungle in Brazil as to be illustrated next. In any case the analogous argument is that the same approach used to establish a Sintic antithesis thereof was based on the Western approach with a highly hypothetical theorization being mocked below that would serve the purpose to prove such a point.

Suppose that we now have cases of some remote Amazon tribes that need new surveys to determine their genetic linguistic affiliation. In a assumingly fashionable manner just like how the Western had come up with a revised hypothesis imposed on the origin of the Vietnamese language as previously mentioned, we would approach two of our imaginative Amazon tribes with a perspective view of the mid-19th century, the period when Western colonists first came to explore a new prospective colony in many parts of the world being less civilized technically; however, the reality is further from the real scenario from what is seen to be contributed to the development of the Vietnamese language in a society that had long absorbed not only the linguistic elements of China but also its culture that had a deep root in Confucianism, Taoism, and the blend of both Mahayana and Hinayana of Buddhism, e.g, Hoahaoism, locally groomed religion that has been crystalized from such cultural and religious admixture. It is so detailed in order to contrast the initial view the Westerners had had about their colonized Annam when they first set their feet in that country nearly two centuries ago.

In a similar fashion, we would then venture into some remotely backward region of the Amazon jungle to do a survey on some unknown tribal languages — being so said for the same reason that until then we had not had an academically recognized name yet for all those seemingly common languages of the linguistic root already known to us under some other guises — and then subsequently discovered that there had existed some basic words in different dialects under investigation that speakers in village "B" were sharing with other speeches in neighboring village "A" which had previously already been investigated.

The issue at stake was that we did not know much about history of related tribes, i.e., those villagers of A and B, so what would we do next? Well, we could work the way Western methodologies had taught us at school. Here are our shortcut approach and cheatsheet being tailored to fit into the framework of academic methodologies. We already knew the names of their other neighbors (called 'Root A'), we might make up one and conveniently lump those newly discovered speeches all into one basket, purportedly, for the stakeholders' own sake — assuming they did not care, knowing nothing about themselves like in the case of Vietnamese in the early 19th century — and our own sanity as well. In other words, intentionally or not, we had just arrogantly excluded our imaginative Amazon tribesmen from partaking the whole supposedly democratic process which somehow applied only those previleged Westerners.

In our exemplified case we were able to come up with a new name such as 'Root A' for a 'new' linguistic family whereas we envisioned that the B speeches must have been descended from the A ancestral language — either based on older forms etymologically or by earlier finds synchronically — and we just had barely learned very little about the B languages up until that point.

In effect all speakers in villages A and B had already had different names for their own tribal speeches — whether or not they were genetically related (they could have been, but remotely further into the distant past) — being embedded in their history and probably recorded in their own unique way that might possibly be preserved and passed down orally in some alternate form such as folklore, folksongs, or proverbs, etc. It is not expected they would be the same convention to fit into the format similar to ours to prove its validity, to say the least. Here we go again, let us arm ourselves with 'superior methodologies' and, consciously or not, all in a conspiracy that we had never bothered to find out their truthful history until and after we had cleverly classed every language spoken there in a neatly devised scheme with what, to our haughty conviction, was far more scientific and superior to theirs.

Comparatively, the imposing manner that we adapted as said was not less different from the approach Western scholars who followed the steps of those Portugese and French missionaries already stationed in the Annamese land beforehand in the 18th century. Specifically, linguistically, they all found it difficult to study the local language with the Chinese-based Nôm characters in order to serve their God's Gospel propaganda to the native. So they made shortcuts by skipping studying Chinese altogether as preliminary steps to understand previous work written on the Vietnamese languages and bluntly invented a whole new scheme to romanize Vietnamese writing orthography, which would later be complete with a set of 'grammar' itself as well that in turn fitted well the level of illiterate mass. The missionaries believed that they had cleverly resolved a thousand-year-old issue that mocked the Annamese scholars on the whole who, nevertheless, unlike those smart Koreans and Japanese of the earlier Middle Age of the East to the Southeast Asia, would have never innovatively dream of phonetically a way that a whole set of alphabet would help them compose exposition in their own language better than those half-baked Chinese ideograms they had insisted standing by the deathbed of the Qing Dynasty till the very end of it, that is, the World War II in 1945 with the defeat of Japanesese troops in both Manchuria Nation and Indo-China. In the Fall that year Vietnamese romanized writting system was offcially adopted by the provisional Vietnamese government of Ho Chi Minh who took over the government from the Japanese surrender. The whole passge above are so detailed as such in order to emphasize the fact the Vietnamese mind have been forged sturdily by the hardened mold of the Chinese mindset.

With respects to the case of romanization of the Chinese language, readers may recall that Western preachers had never succeeded in China in the end with similar romanizing conversion schemes due to the stubborness of the local people given most of the population had been illiterate for the most part, temporally and spatially. That was worse than the Annamese case, though. Specifically, the case of Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer became a matter of technicality in coining a new terminology at the turn of the previous century. The Westerners doubtless turned out not only transcend but also outwit the Chinese model. Like in the case of our imaginative Amazon's tribal languages abocve, while ignoring all about whatsoever without the need to acknowledge the historical Chinese role in their language as many 19th-centuried linguists' ignorance of Chinese, it was a clever thing for them to have done that they coined the new terminology using Austro- to mean "south" and Asiatic a linguistic family of Asia for a language family that likely originated from the south, including China South region, as opposed to the China North. Their creation of the Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer hypothesis hence encompassed every language spoken in that northern hemisphere of Southeast Asia and China South for their shared roots of commonalities from which even the Chinese also borrowed their words. At the same time, the terms 'Sino' and 'Sintic' were discredited as being devised for political reasons, e.g., inclusion of Cantonese and Fukienese dialects of Sino-Tibetan family, to say the least.

In the real world, to be fair, any theories will possibly change over the time one way or another, exactly like linguistic changes that we all now reckon due to its volatility. For example, those Zhuang and Daic languages are now regarded as of Tai-Kadai linguistic family after a long time they were classed in the Sino-Tibetan languages. For the same reason, unlike natural sciences, any early conclusion thereof is still inconclusive and hypothetical for the Austroasiastic theory as well, at least until every single issue is basically resolved once and for all, like what has settled for the case of Indo-European languages, for which we all accepted, which also left the legacy of analytical tools that have been utilized to mitigate all the issues the Indo-European origin of the languages of Pali, Sanskrit, Greek, Roman, Germanic, Baltaic, Gaul, etc..

In the case of our Sinitic-Vietnamese study, at first we started out with the intention to reclassify the Vietnamese language in the rightful sub-family as the name implicated. To make it happen, academic consensus must be reached in acknowledgement that the existence of the ancient Yue language family did exist and can be verified through historical records that the ancient sound spelled out as 'Jyet', or possibly 'Bjyet', being recognized in modern Mandarin as 'Yue', though, of which words were quoted in ancient dictionary such as Erya (爾雅) for diplomatic communication throughout the Spring and Autumn Period, which is further evidenced by means of major "dialects" such as the three prominent Cantonese, Fukienese, and Wu speeches; this fact helps elevate their Vietic counterpart to the ancient Yue origin. As a matter of fact, those of the Zhuang or the Daic people as of Tai-Kadai had long been grouped by previous Western classification that later became separate linguistic branches under the Sino-Tibetan linguistic family by all China's official institutions.

The foregoing passage on the Cantonese, Fukienese, and Wu dialects is admittedly our attempt to justify our new action on regrouping Vietnamese into the same linguistic sub-family in order to be on par with those languages that have been officially endorsed by Chinese government's institutes that boldly list the three major Yue dialects under Sinitic branches of Sinio-Tibetan family. In the battle to fight for the truthfulness of information in modern time, China's propaganda's appratus has been employing a whole division to edit and counter-edit any 'misinformation' on major media on the internet, including Wikipedia.org, Facebook, etc., to shape the view of the public into correctness mold. Methodologically, to have finalized on such major additions to the Sino-Tibetan linguistic family, similar linguistic analytical tools need to be utilized. At the same time, historical linguists also need to recognize the Sinicizing force that has incessantly asserted itself on the Yue substratum of which aboriginal elements could be found existing deeply underneath the Chinese superstrata at the top. As a matter of fact, the truth is not that so remote past in time since we could prove that. In addition the "Erya" language, the Yue linguistic elements had preceded before any archaic Chinese elements that later became integral parts of all Sinitic languages as well. (See De Lacouperie. 1965. Ibid.)

What shall we possibly do to mitigate conflicts in the Sino-Tibetan stand in reference to those postulated Mon-Khmer basic words? When we come up with our new Yue-Sinitic theory for the Vietnamese language, we have also adopted the so-called objective and scientific approaches as they have been used by the Western Austroasiatic theorists, of which the same way has been illustrated in the highly imaginary case study of the Amazon A and B languages above. We bypass, nevertheless, rather than to repeat results of older Sino-Tibetan theorization, by establishing the Yue foundation dedicated as its roots with all the Sino-Tibetan etyma that existed in other Sino-Tibetan languages, including those unsuspected Chinese dialects, such as Northeastern Mandarin in some peculiar semantic expressions, e.g., "順路" shùnlù ("thuậnlối" or 'on the same way') being swapped with "順道" shùndào ("thuậnđường" or 'on the same road') by southern speech. With such simple compounds we could talk a whole lot more on many linguistic aspects, say, Western methodologies, and we would work the same way as the Austroasiatic theorists had done for the Mon-Khmer linguistic sub-family with the hypothesis of their genetic affiliation with Vietnamese. Specifically, we would follow the same process with mechanisms and tools to explore the true nature of the etymology of modern Vietnamese words. To make the story short, for all of what the author would like to emphasize for now, many archaic Chinese words of Sino-Tibetan origin basically still lie dormant buried here and there physically in ancient Chinese classical books and archaeological geo-substrata alike; they had existed there long before the Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer theory came alive with Middle Vietnamese contacts with the Khmer language in the south. Middle Vietnamese was not ancient native language spoken on the land where the Vietnamese resettled and other late emigrants who kept moving on following the upstreeam branch of the Mekong River into the Tonle Sap Lake deep inside Cambodia. In other words, it an important historical fact that all the Kinh descents of the last known Vietnamese emigrants to the southern territory — which used to belong to the Chamic people of Austronesian Malayo-Polynesian origin — barely resettled in those stretches of land after the 17th century, having mixed with local Mon-Khmer speakers less than 360 years ago.

Comparatively, in a sense, Austroasiatic linguistic claims are analogous to similar acclamation on the cultural heritage exerted by local Vietnamese archaeologists who, more than once, have been singled out and mocked for their greedy jealousy in embracing all artifacts of the Sahuỳnh and Óc-Eo civilizations excavated in the central and southern parts of today's Vietnam. They have undauntedly accredited those cultural relics as creation of their "Vietnamese ancestors" because they represent both advanced progress of a civilized society and its connection with languages as well. It is somewhat mechanical and dull to simply quote and re-quote the same old Austroasiatic basic etyma from one scholar to another, of which their lexical origins were supplied by "seasonal linguists of some summer's institute". For those who actually did not know the Mon-Khmer languages under investigation very well and they, in turn, mostly relied on translated versions mainly provided by local informants and interpreters, theirs being only casual translation without knowledge of etymological linguistics, in place of true cognates obtained methodologically from linguistic rules. In other words, local guides being not stakeholders, at the time, they might have not been aware of importance of their work that would finally exert so significant imprints in the Vietnamese historical linguistic records. Similar linguistic claims of the same sort on the etymological aspect were actually based on a limited number of cognates of basic words between the Vietnamese and Mon-Khmer languages that have been repeatedly cited by linguists in the Austroasiatic camp who bet on its data as being prepared with well-defined methodologies back in the mid-1960s. Specifically, it is ill advice to prove a case by revisiting the same old quoted basic words, e.g., the popular 5 counting numbers, local exotic fruits and flora, as well as other low-frequency basic words... from many distinctive Mon-Khmer isoglosses that are specific to certain regions. Amusingly, newcomers in the field have seen themselves repeating the same pattern by starting it as a springboard therefrom and elevated them innovatively to the next level on the old platform. That is to say, it is, based on words deemed to have originated from the Mon-Khmer languages. There we go again, merry-go-around, that those wordlists made available to them were in effect prepared by those linguists who were funded by some foundation for a summer's fieldtrip to conduct a survey on some 'exotic' language considered as still in its existence in one of the last frontiers in Asia besides Africa, i.e., those Mon-Khmer speeches spoken by minorities in remote mountainous highlands in South Vietnam spilled out at the height of the Vietnam War in the later half of 60s and early '70s of the 20th century. To say the least those with institutinally grant-funded scholars themselves along with their local Mon-Khmer guides were in effect virtually semi-illiterate in the languages involved, linguistically. That said, their cited basic words, if applicable, would have been likely dated ages ago that they could hardly maintain similar phonological appearance unless they were recent loanwords.

To steer away from the disconcerting data due to linguistic admixture and discrepancy all quite recently, we need to inspire the next generation of linguists freshly from colleges to venture into the field of Sinitic-Vietnamese historical linguistics. To succeed in such movement we shall first find way to first clear the mislabelling of Vietnamese as an Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer language for various reasons. Firstly, it is noted that its theorization dated back as early as the beginning of the previous century. In terms of its credibility, secondly, shadowing figures as such in the field would only impede their advancement for the reason that those journeymen would put in more of their trust on the Mon-Khmer theory of the Vietnamese origin as their mentors taugt them at school; they will have limited choice but join the Austroasiatic linguistic circle because they will feel much more at ease then. Thirdly, they still continue to use those old data prepared by pioneer works described as erroneous academics and make it their starting point for the next steps on studying the Vietnamese etymology as we wish they all would do. While in process, hopefully, we all can brush aside any bitterness and sarcasm having popped up here and there as long as no upholders at stake that would effectively uproot our critically theoretical foundation one way or another, that is very unlikely, then any fruition of past studies can asist newcomers in paving the way for any new breakthrough in this field.

As we come closer to jump start the Sino-Tibetan algorithmic deduction all over again, let us make clear that there would be then plenty of room for one's own free interpretation as a linguist in either camp. Ideally, be it some Austroasiatic way on their field trip or they may be inclined to lay trust in a Mon-Khmer local guide, then that should be a linguistic institutionally-trained Khmer native speaker to be completely competent in, at the very least, both Vietnamese and a Mon-Khmer language of his own. It would have been much better if those language guides who had already worked with Austroasiatic specialists on some other field trips who are familiar with other Mon-Khmer language and, at the same time, have deep knowledge of Chinese; it would be a plus for those who possess an ability to decipher Archaic Chinese as well, linguistically speaking, to say the least. For the latter emphasis, the readers will see the reason why when comparing the Mon-Khmer lists with those of affirmatively readable Ancient Chinese, it is known to they have existed in Vietnamese for some unspecified millennia ago, for example, names of the 12 animals in the earthly zodiac table that the Khmer happen to share as well where ‘nămmèo' = 卯年 măonián must be 'year of the cat' not that of 'the rabit', and so on.

Those Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer specialists who first tabulated the Mon-Khmer - Vietnamese cognates still lack language feelings and competent proficiency. At the same time, a mastery level of all those living languages to reach native fluency are not only required but also a 'true feeling for the related language' demanded for a local guide that is not simply a translator because they may miss something that only a linguist can catch on. Talking of speaking 'the language with feelings', one would know why with thousands of Chinese words being found as cognates with those of Vietnamese, which has only occurred to a keen and alert mind but that only come with the 'linguistic feeling' that 'exploding words' kept bursting out in such a way that no parallel pattern has ever been found in any Mon-Khmer languages. As a matter of fact, only competent historical linguist can see the sound change patterns that make sense out of the sounds in the compounds such as '繼母 jìmǔ' (SV "kếmẫu"), 母雞 mǔjī (SV "mẫukê"), 舅母 jìumǔ (SV "cựumẫu") to differentiate the meanings in Chinese while resulting in respective cognates varied greatly in pronunciation in Sinitic Vietnamese, namely, 'mẹghẻ' vs. 'mẹkế' (step-mother), 'gàmẹ' vs. 'gàmái' (hen), and 'cậumợ' vs. the constracted 'mợ' (maternal ancle's wife), of which the latter expanded its meanings to cover other different concepts such as "uncle and aunty (his wife)" as addressed by the maternal uncle's nephew or niece, all on top of the other extended meaning "parents" called by their own children in northern dialect. All said, all the variant sounds can be traced back and matched with different Old, Middle, modern or dialectal Chinese. In other words, no Mon-Khmer equivalents as such can match the Chinese cultural elements that have penetrated deeply into each of the Vietnamese cognates at different levels and in such subtle details, that is, how the concept "mẫu" is different from "mẹ", "mợ", and "mái", not to mention that many of currently cited Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer basic words might be no longer creditable for the reason that, from our new Sino-Tibetan findings, the same basic ones used to be regarded as Mon-Khmer and Vietnamese cognates now point to other roots in Sino-Tibetan etymologies as to be revealed in this research! (Shafer, 1966 - 1974. Refer to Sino-Tibetan etyma.)

I can continue on to talk endlessly about the Vietnamese etymological matters in relation with that of Chinese, elaborating on the etymology involved in Ancient Chinese and other Chinese dialects. It is not that I have been academically trained historical linguist nor know Khmer. When Henri Maspero (Les Langues du Monde. 1952. pp. 582-83) said that the Mon-Khmer languages made up the Vietnamese substratra and it is apparent that the Vietnamese grammar is that of Thai and Mon-Khmer languages, I know immediately what is wrong with the author's erroneous statement and see what caused the author to think so because of deficiency of research in the Mon-Khmer linguistic matters. With my fair mastery of the Vietnamese and Chinese languages at the level of native fluency and academic knowledge in their historical linguistics I see what other Mon-Khmer specialists with similar competency in related languages did not see. On the one hand, mechanically, they could manage to analyze each and every elements postulated those Mon-Khmer forms that are cognate to the Vietnamese equivalents. On the other hand, however, they do not speak Vietnamese and Chinese with a 'feeling', the way being felt by learned natives who are bilingual and could talk about those languages with etymological linguistic analysis. From anyone who fits into such qualifications, we all want to hear what that individual has to say about the Vietnamese etymology of Sinitic-Vietnamese origin. To understand the significance of such implication, on the same level of playing field, let us ask yourselves the question, "how many of us who speak, read, and write well the English language could talk about relevant issues of the English linguistics?" For what I have read from those who were writing about the subjects in their own mother tongue at college level, they barely pass the communicative skills in the target language that they are discussing.

Specifically in the field of historical linguistics of Chinese and Vietnamese etymologies, Sinitic-Vietnamese words could be cognate to one etymon that could give rise to other Chinese words and in turn appear in variant forms, e.g., "quả" (fruit) 果 guǒ vs. 菓 guǒ, "đậu" (bean) 豆 dòu vs. 荳 dòu... while original forms may be recycled to mean something else. Syllabically, differentiated sound bits may evolve from different layers, so knowing barely a layer or two of an etymon involved is not enough because for the same concept the phonology of each word can be different. As readers will learn later, many Chinese and Vietnamese words have evolved from three or more etymological layers such as that of the etymological layer of duplicates that are also known as 'doublets', i.e., words from the same source. For example, Chinese 會 huì (SV hội) could have evolved into VS 'hiểu', 'họp', 'hụi', etc., meaning 'fair', 'understand', 'meeting', 'trust fund', respectively, and for 川 chuān, 水 shuǐ, and 江 jiāng, all possibly cognate to Vietic */krong/ or VS 'sông' (river) along with several other derivatives, especially with those basic Chinese ideographs, say, 川 chuān for 'suối' => 泉 quán (creek), 水 shuǐ 'nước' (water) => for 'sông' 江 jiāng that was in turn evolved from 長江 Chángjiāng (aka 揚子江 Yangtze River), repectively.

In the examples cited above, it is not coincident that those experts, who are most likely from the Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer camp, have failed to capture the formation of polysyllabic doublets derived from Sinitic variants. For Mon-Khmer etyma they used to cite samples having probably been repackaged from somebody's else, oftentimes having Vietnamese words mispelled or mislabeled miserably, even in their academic publications, which could not be blamed as repetitive typos. While there is no doubt on those specialists' expertise and contributions to this field of study in Vietnamese, it is noted that their works are incomplete in such cases, hernce, biased and inaccurate. The fact that Vietnamese cognates were also found in Mon-Khmer and Thai languages does not mean they had to originate therefrom, which can be explained that they all could have shared some proto-forms in ancient times before the same proto-form penetrated into the archaic Chinese as well. Thpiere is no need to finger pointing here, but as we examine some basic words cited by Henri Maspero (Ibid. 1952. p.p. 582-83), we can see that the Vietnamese etyma were grouped in either Mon-Khmer or Thai roots. For example, for those of Mon-Khmer origin, the author lists "sông" (river), "rú" (forest), "chim" (bird), "lúa" (paddy), "áo" (shirt), and for the Thai roots,"gà" (chicken), "vịt" (duck), "gạo" (rice), etc., and only then found the Chinese as preiously mentioned, that is, 江 jiāng, 野 yě, 禽 qín, 來 lái, 襖 ào, 雞 jī, 鴄 pī, 稻 dào, respectively, not to mention their possible doublets as follows in respective order, 水 shuǐ, 粗 cū, 隹 zhuī, 稻 dào, 衣 yī, 鷄 jī, 鶩 wù, 穀 gǔ. We can elaborate on the case of 江 jiāng, and recognize that this form specifically designates 'river' only in China South region, such as 湄江 Méijiāng (Mekong – modern transcription 湄公河 Méigōnghé) and 長江 Chángjiāng (Yangtze River) that both originated from 三江源 Sānjiāngyuán (Three River Upper Reach) in the Tibetan and Qinghai high plateau; they do not from the Tonle Sap Lake in Cambodia, in any cases, where 'Tonle' means 'river' while /-krong/ means 'city' not 'river', to be exact. Amusingly, by the same token, the word for 'the Red River' in North Vietnam after the name "SôngHồng", of which the name is called in Chinese as 紅河 Hónghé (SV "Hồnghà"), not 紅江 Hóngjiāng (SV "Hồnggiang"), for which sometimes the Vietnamese even call 'Sông Hồnghà', that is, 紅河江 Hónghéjiāng, similar to the way 湄公河 Méigōnghé is constructed.

In any cases, the term "Austroasiatic" as a linguistic family, technically speaking, was coined by Western linguists out of their pressing thrist for a quick academic resolution to classify the Vietnamese language sans Chinese. The Western scholars found a perfect shortcut to bypass the China in the far north as it happened the Vietnamese speakers had been found living among Khmer speakers further in the south. It at first appeared they had been overwhelmed with those etyma from the Sino-Tibetan family in the Vietnamese language as late as at the turn of the 20th century. It is of no surprising that they were uncertain about what class name to cover them; it was just like the similar case of those mystic related East Asian languages left unresolved for as late as until the 17th century (see Lunbæk, Knud. 1986. T.S. Bayer (1694-1738), Pioneer Sinologist) It is then assumed that first Austroasiatic pioneers would simply invented a new terminology for the unclassified linguistic umbrella that they had been holding. Apparently from beginning they might choose to ignore or simply be unaware of what had been in store for those Vietic, Daic, Mon, etc., modern living languages spoken widely in contemporary Vietnam, Thailand, Laos, and China South, as postulated in the same Sino-Tibetan theory, that were encompassed in their investigation throughout the Indo-Chinese region finding variant dialects spoken in nothern parts had already been already grouped within the common name known as the "Yue languages". That concept was later expanded to include the so-called Taic language family to account for both Daic-Kadai and the Yue languages that include the Vietnamese, the Zhuang, Cantonese, Fukienese, Wu languages, etc. Historically, the Chinese term "Yue" was long in use under different transcriptive characters for some kind of axe-like weapons, i.e., 粵, 戉, 鉞, and the tribesmen who used them as noted in ancient Chinese annals and classical works. Meanwhile, the term "Taic" was a later ad hoc added-on invention to cover what encompassed the ancient language spoken in the Chu State as well where it was seen as the mother tongue of the Daic-Kadai daughter's languages and their sister's languages [ which could be those of the Zhuang, or 'Nùng' in Vietnamese, an ancestral language of Cantonese long before the Chinese ] of the Yue (De Lacouperie. Ibid. 1867 [1965]). We could speculate that the same old Yue cards were "re-shuttled" to compile a newly formulated deck on which a brand new theory was known later as Austroasiatic linguistic family that encompassed the Mon-Khmer sub-family. It is further postulated that in the absence of knowledge of oriental philology, the classification of Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer for the Vietnamese language was first initiated by new generation of Western linguistic enthusiasts eagerly to establish new footing in historical linguistic frontiers as having mushroomed with new schools due to novel methologies in humanities. Any linguists, of course, could certainly call a newly 'discovered' linguistic family by any other name as they see fit, especially at the turn of the 20th century. That is how those Austroasiatic initiators walked away with "Austro-Asiatic" (AA) without being scrutinized further for their having created a shortcut conveniently for themselves and those latecomers in an academic field actually already existing by another name, to say the least.

Seeing Austroasiatic as a misnomer for classifying the affiliation of the Vietnamese etymology, the author has advertised the term "Sinitic-Vietnamese" to implicate that the Sinitic-Yue linguistic sub-family that had contributed to the develoment of the modern Vietnamese language. That is to say, the Vietic linguistic entities — of the ancestral Vietnamese language after the breakup of the Vietmuong sub-family — were in effect the results of the Sinitic elements having grown on top of the Yue stratra, not excluding the plausibiliy that the Sinitic stratum had even been an admixture of the Yue elements, to explicate the cognacy of those Chinese and Vietnamese elements, e.g., 江 jiāng for VS 'sông' (river), 椰 yé VS 'dừa' (coconut), or 糖 táng SV 'đường' (sugar), etc., while they are considered as aboriginal Yue basic words, specifically in this historical linguistic realm.

Vietic is a conceptual variable before the the breakup of the Vietmuong, to be exact, in the continuum of what has been conferred upon, from the "Yue" that was long documented in all ancient Chnese records with different transliteration of /Jyet/ 戉, 粵, 越, etc. — a grand designation also for most Yue-derived speeches still being spoken by most minorities in both regions of China-South and North Vietnam — to the early period of the formation of Annamese as being grouped within the Sino-Tibetan linguistic family with all the Sinitic-Vietnamese etyma that are later known only as words of Chinese origin (unsurprisingly, Vietnam having been always overshadowed by the Big China). To save our sanity amid perceptional confusion, terminologically, the author replaces Chinese with Sinitic given the latter concept having been a genetic mixture of the Taic-Yue and an unknown factor of probably ancient Tibetan, racially and linguistically, not an unknown entity as Jerry Norman (1988) once referred to as "extinct foreign elements". In any case, the purpose here is to rebut the misconception of Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer origin of some Vietnamese basic words by coining the academically designated Sinitic term for the so-called "Vietnamese of Chinese origin", hence, Sintic-Vietnamese (VS), so as to re-instate the rightful Sino-Tibetan status of its linguistic classification.

By doing so, we could avoid certain ambiguities caused by the implication of terminology Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer. For instance, besides the term 'Sinitic' as a misnomer as aforesaid – i.e., "the Yue" – the designated Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer was originally devised to covertly mean what its originators had obviously intended was to include all languages that originated deeply from the south, that is, further in the south with respect to where China South is located in the north. Such classification doubtless implicated genetic affiliation of a linguistic source rooted deeply in Southeast Asia with no room for compromise — recall the cases of archaeological artifacts found in the same region of which their masters must have been Mon-Khmer speakers — and, therefore, the term does not indicate pecisely what we are really up to, i.e., the Yue origin of those Sinitic-Vietnamese vocabularies, e.g., 'cún' (puppy) and 'lợn' (piglet), both of which could be equally true also for those of Chinese '犬' quăn (SV khuyển) and 腞 dùn (SV đốn), respectively. That is how our own newly-coined term "Sinitic-Yue" got into the picture under the false guise of a sole "Sinitic" canopy.

Those renown theorists who have long led the Austroasitic Mon-Khmer way for lately collegiate graduates from Vietnamese studies to follow have been successful in using Western methodologies in Indo-European (IE) languages. Instead of airing a business as usual attitude as currently projected by many contemporary linguists, it is probably time now to try out our new renovative approach to the Yue and Sino-Tibetan theorization as to be presented in this survey.

In any cases bear in mind that in spite of its long-establised maturity, current theorization on the Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer genetic affinity of Vietnamese is just another hypothesis. It is still an open-ended work since we could write in length valid antitheses about it as things Sinitic-Vietnamese have developed. The Austroasiatic theory is always an on-going process of reworking, which has seemingly moved further away from its finality as more theorists of its camp have come joining in and their works exposed errors in, say, mistaking Sino-Vietnamese words for those Sinitic-Vietnamese ones then reaching wrong conclusion therefrom. The Western methodolody is logical and rational, but not always truthful. In the linguistic world there exists no such thing as an absolute maxim, especially in the study field of etymological and historical linguistics. Among other things, with no history to back it up, it has never given supporting written records and satisfactorily explained all plausible cognacy of Sinitic elements that exist in Vietnamese at the same time. We will do so as needs arise; we could at any times modify age-old theories accordingly to reflect new findings, this time solidly strenthened with Sino-Tibetan etyma in Vietnamese basic words.

For the Sino-Tibetan school of thought and its fruition resulted from prior studies can still provide the linguistic world with its etymological, historical, and theoretical merits, such as preliminary identification of most of related Sino-Tibetan etymologies, reconstruction of their archaic forms, theorization of Old Chinese consonantal clusters and tripthongs, or hypotheses on tonogenesis and tone development, etc., all pave the way to go further to explore and build our Sinitic Vietnamese theory. For those long-recognized Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer basic words, the author will attempt to repackage them, if any, e.g., 'lá' (leaf) { < 'ha' (Mon-Khmer) < hala < *pa (Chamic) } vs. { < Chin. 葉 yè, dié, shè, xiè < MC jep < OC *lhap < OC *lap < PC **lɒp } vs. { < Proto-Austro-Asiatic: *la, Proto-Katuic: *la, Proto-Bahnaric: *la, Khmer: sla:, Proto-Vietic: *laʔ, s-, Proto-Monic: *la:ʔ, Proto-Palaungic: *laʔ, Proto-Khmu: *laʔ, Proto-Viet-Muong: *laʔ...}, etc. in this paper with newly-resurfaced evidences, unprecedentedly, coming from over 420 fundamental etyma pointing mainly to the direction of Sino-Tibetan theory based on Shafer's list of Sino-Tibetan etymologies that, ironically, has been in existence for many decades but nobody seems to have taken notice. (Shafer, 1966 - 1974. Refer to Sino-Tibetan etymologies)

We would return to the matter of Sinitic-Vietnamese core words that proves the etymological affiliation among Vietnamese, Chinese, and the Yue languages — for all that makes up the modern Vietnamese language — because their interconnection dated back only in a period of less than 3,000 years ago based Chinese records. Chinese philologists in ancient times, within their own expertise and scholarly capacity, have been well aware of all those etymological commonalities in the ancient Yue language involved, i.e., proto-Daic, proto-Vietic, proto-Cantonese, proto-Fukienese, etc., of which their variants were recognized and recorded in the giant Kangxi Dictionary (康熙字典) as well, which could teach us a thing or two about their origin, long before any new Western concepts have ever come along with the Austroasiatic mainstream.

As the Austroasiatic initiators devised a new theory of Mon-Khmer origin of Vietnamese, they bluntly rejected the pre-existing theory that already grouped Vietnamese in the Sino-Tibetan linguistic family which all had been molded in line with other Chinese dialects — sans goverment's institutional intervention — such as Cantonese and Fukienese dialects. When they came up with the concept "Mon-Khmer linguistic sub-family" (MK) and added the terminology under the larger "Austro-Asiatic family" (AA), the Western linguists had, in effect, preemptively overpowered Chinese linguists from bringing up any more theories on Sino-centric languages, as manifested by several Chinese ancient rhyming books. To be exact, the Austroasiatic specialists' attempt to displace a pretty old study field in Chinese phonological linguistics appeared to be of some conspiracy to provide a shortcut and detour around early Chinese peccability in Western accademics. (See Lunbæk, Knud. 1986. Ibid.) In other words, they simply tried to avoid steep learning curves in Sinology.

The approach that the Austroasiatic theorists took to formulate their theory resulted in displacement of the historical role of variant ancient Yue languages that had contributed to Chinese, at least their lexicons — similar to what those neighboring Mon-Khmer speeches did to Annamese — in variant forms of which many are buried deeply in Chinese classics as many words were collected in the Kangxi Dictionary, e.g., 簍 lóu for 'rỗ' (basket) which could be a doublet of 籮 luó, or 帔 pèi and 襣 bì for 'váy' (skirt), etc.

In effect, ancient Chinese rime books, compiled by Chinese philologists, had never fully been appreciated in the Western linguistic cirlce until the early 20th century with newly emerged interests in Chinese historical linguistics led by well-known scholars such as Haudricourt, Kargren, Forest, Maspero, etc. Specifically in the case of Chinese and Vietnamese sound changes, those Western pioneers in Ancient Chinese, right from beginning, reckoned the validity of the Annamese role in preserving certain characteristics of Ancient Chinese phonology. Indeed, Sinitic-Vietnamese sound values could be and have been utilized in the reconstruction of Old Chinese, which was characteristically involved in a similar fashion as that of the evolution of Cantonese and Fukienese, respectively. As a matter of fact, they could be proved to be of "Yue" origin via the study of Sinitic-Vietnamese etymology as well.

As pointed out earlier, one of the main reasons for the Austroasiatic pioneers to have created their new theory as they did was likely that it was much easier for them to start afresh rather than acknowledging the theorization of the Yue root that had already existed hundreds of years behind them. The creators of the Austroasiatic hypothesis were totally estranged from the world of ancient Chinese historical linguistics where records of the Yue languages could be identified. No matter what is being conferred upon Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer aspects of it, for their similarities and commonalities, Vietnamese, Cantonese, and Fukienese undoubtedly originated from the same Yue root in ancient China South.

Linguistic elements of the historical Yue languages once spoken in the vast China South region in ancient times are also present in other five major different Chinese dialects as well, such as those of northern Mandarin and southern Wu dialects. Intriguingly with the same nature of its obvious Sinicization, the Vietnamese was instead put under a different guise of the Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer hypothesis. It, nevertheless, could not nullify the validity of the same Sino-Tibetan classification for those two former dialectal groups.

There are also, moreover, undeniable affiliates in many other Sino-Tibetan etymologies. This paper will go on to tackle some other issues as well with regards to their true ancestral root and straighten up records of their linguistic affinity as we come along in unraveling basic words in Sino-Tibetan etymologies that have been found to be cognate to those in Vietnamese. To speed up the work, be prepared to accept certain linguistic norms and premises that we shall not explain what is assumed that journeyman linguists must have known, such as common sound change rules, say, 蒜 suàn (SV toán) ~ VS 'tỏi' (garlic), 鮮 xiān (SV tiên) ~ VS 'tươi' (fresh), or 'sumvầy' 團圓 tuányuán (SV "đoànviên"), that is, with no further explanation of the condition { [xxx] / [s-, x-] ~ [t-], [-n] ~ [-i] }, etc.

Readers will see later on that the very same reason of what makes scores of those shared basic words in Vietnamese plausibly cognate to those in other Austroasiatic languages is equally applied to etyma uncovered in Sino-Tibetan languages per se, that is, their validity of cognacy are on equal footing. That is to say, with certain etyma that are cognate to those in the Austro-Asiatic Mon-Khmer words so they originated from the that sub-family, one can say the same for the Sino-Tibetan side, all just in the name depending which name has been picked first. As a matter of fact, it is amazing with much more cognacy (as to be presented in Chapter X on the Sino-Tibetan etymologies) bolted down with fundamental etyma that is amounted to over 420 plus items. Their common etyma embrace inclusively basic categories that have permeated throughout all languages spoken in the regions of not only China South and Southeast Asia, but East Asia as well.

If all that takes to make a postulated language a reckoned member of the Sino-Tibetan linguistic family is their similar etyma without taking into consideration of any other linguistic features, the Sinitic-Vietnamese etyma could also make Vietnamese instantly one of the Sino-Tibetan languages because of its all intrinsic Sinicized features, so do those Sinicized Cantonese and Fukienese. The same axiom applies to the Austroasiatic argumentation that the Vietnamese relationship with Mon-Khmer languages is characteristically parallel based on those of Austroasiatic basic lexical items. This statement is another paraphrase of what has been disscussed before.

Anthropologically, except for Haudricourt's model of tonogenesis, the Austroasiatic camp hitherto has offered no historical records to back up the process of how the Khmer elements had evolved into those of Vietnamese per its theory. Culturally speaking, the Austroasiatic specialists only further pushed related Mon-Khmer entities farther from the overall picture of the Annam's new cultural admixture of Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism that are characterized in Vietnamese deeply as well, like what appears in any Sinitic-centric languages, which does not show in the neighboring Mon-Khmer languages. Historical facts show that the Annam's national development only began to have contacts with the Champa Kingdom — an Indian turned Islamic state in China's Warring Periods — started under the rule of the Eastern Han Dynasty, as recorded in Chinese annals, that was located in south of Annam's border, right where in the territory that had long belonged to its precursor state known as Lâmấp (or Linyi 林邑, c. 197-750 A.D.) The Champ Kingdom also lasted from the 8th to the early 18th centuries. Both states had chronologically acted as an effective cushion between Annam in the north and its Khmer neighbors in the south, that is, long before and after Annam became a soveignty in 939. In a recent study, Michel Ferlus (2012) points out that there existed the possibility that the influence of the ancient Annamese language spreading from Annam's northeasthern to the southwestern region and westward all the way to India, hence, its loanwords to Mon-Khmer and Munda languages in the Austroasiatic model, following a trade route from Annam throughout the 3rd to the 8th centuries. His theory is yet another example of the fruitfulness of interdisciplinary approach in linguistics and history, the latter of which is surely a missing link in the Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer theory (M).

To set the record straight, nevertheless, be it an Austroasiatic theory or not, it does not matter much whether initially early in ancient times the proto-Vietic languages truly originated from the Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer family (K). In actuality, all it counts is what makes up the Vietnamese language as we know it as a living language, holistically, the one and only with all the attributes considered as natural and integral totality per se. To easily grasp such disputable point, analogically, let us take English as a better example as it can be seen somewhat a parallel case with regards to its historically unrestrained absorption of foreign elements that have grown on top of its own lesser core. When we look at this popular modern language, in other words, we see English presents itself in its wholeness, not just only either the Anglo-Saxon, Welsh, Scots, Gothic, or the Germanic part of it, but also those of the Norman, Romanic, and Greek languages, essentially present in every linguistic components, including those of native and foreign origin, that wholly make up the richly modern English language. It is, therefore, important that we should also treat Vietnamese similarly with a holistic approach, looking for the truthfulness of the linguistic core matter that it shows through in the way the whole language presents itself in its entirety, the modern Vietnamese language, so to speak.

In analyzing the linguistic characteristics and traits of a living language, let us not to neglect racial makeups of the majority of local speakers who might not speak the native language as spoken by the natives. In Vietnam, throughout the length of its 2,000km long S-shaped geo-political map that was formed at intervals from the north to the south over the period of 2,000 years, the Kinh majority have been formed by intermarriages with local peope, e.g., the Chams, Mon, Khmer, Chinese-Tchiewchow, etc., but the Vietnamese Kinh do not speak the local languages as the moved in and resttled in the lately annexed territory. That is the case with Vietnamese vs. Khmer when the Khmer roots have been imposed on ancient Annamese and their speakers. Meanwhile, so said, on the other hand, Vietnamese its has never been a pure language, but, etymologically, a hybrid Sinitic language. In the world there exist a few of well-known cases whose mother tongue is only a creole, or an outlander's language. For example, while descendants of previous Amazon slaves locally born in Haiti speak Haitian-French; for Jamaicans, Bahamians, and other descents of Africans and native Americans speak English in our contemporary era, neither of the latter English speakers qualify as genetically affiliated with the language they speak in any way. That axiom analogously leads to a verdict that even though Vietnamese has absorbed scores of Mon-Khmer basic words as they moved in and resettled among the native in each locality, i.e., the Thai-blanc and -noir, the Daic, the Zhuang, the Chamic, the Mon, the Khmer, etc., and being in the spotlight, anthropologically, the Khmer language that the modern 'Cambodian' speak had nothing to do with the former Annamese in terms of linguistic affiliation before the 16th century for the reason that the aboriginal language that the historical Vietnamese heroines Trưng Sisters and their people spoke some 2,000 years ago was certainly different from what has evolved into official Vietnamese spoken by Hanoians in the modern time. Hence, naturally there is no doubt that the core matter of the racial origin had long been uprooted from its foundation in some prehistoric era, so the Mon-Khmer connection with ancient Vietnamese are, linguistically, meagerly loanwords.

Regarding its hybrid nature as previously mentioned, characteristically speaking, regardless of its genetic affiliation of linguistic classification, Vietnamese appears to be a composite language — that is built on the phonological model {(C)+V+(C)} + {(C)+V+(C)} + {(C)+V+(C)} +... — that has blended in itself the Yue core of the same nature with all those later similarly traceable Chinese elements — of which the latter might also inherit from the merger of the earlier aboriginal Taic linguistic elements — ancestral language of all mother tongues spoken in China South and beyond — in some descendant languages that were once spoken by the "Chu" (楚) populace — along with, for the last 800 years after Annam had annexed its neigboring states, other notably possible Chamic and Mon-Khmer native lexicons with theirs actually holding only a meager share of their etyma in Vietnamese, many of which are considered as basic words, though, which was a taut spot where Austroasiatic specialists had focused on to have founded its Mon-Khmer hypothesis.

As a matter of fact, attempts by the Austroasiatic theorists to bring Mon-Khmer languages a bit closer to Vietnamese were marked by painstaking with their elaboration on scores of Vietnamese basic words being posited plausibly as Mon-Khmer cognates. That is insufficient in a way where grouping affiliated languages together under one class cannot be based solely on their basic wordlists. At best one can put them under one ctegorical umbrella as distant affilliates from prehistoric past by analogy when many ancient languages deem to have early linguistic contacts to meet the need of economica activities such as bartering and trading. Throughout the period of the last 2 millenia, comparable Chinese components have gradually merged into the Vietnamese language to fulfill the very same needs but with historical records for us to check. Under such expanding circumstances, determining factors for a linguistic classification are not then limited only within the realm of basic words but also opening up unique traits and attributes embedded in the nucleus of each word that can be regarded as its DNA built with a common gene. Their shared peculiarities, in fact, are so unique that only a few Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer elements will ever match each and every linguistic feature, including tones and syllabic makeups. Such commonalities are intrinsic, interestingly, which does not exist even in most Sino-Tibetan languages, e.g., Tibetan vs. Chinese, let alone those of Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer.

Terminologically, the term Sinitic-Yue is based on the concept of the 'Yue' (越) as it and its other old variants appear in Chinese historical records referring to an ancestral line of the 'Yue' people. The term 'Viet' is not chosen here for a historical reason and because, at the same time, it could become a misnomer in terms of pronunciation even though its sound could be close the ancient articulation of /wjat/ or /jyet/ like the Cantonese 粵 jyut6. The adoption of "Yue", like that of "Sinitic", is more academic to be representative of all descendants of the ancient Yue. WIth such designation one will be able to fend off arguments that other linguistic attributes shared by both Vietnamese and Chinese, such as tones or syllabic segments that suggest an overt genetic affiliation, which was dismissed by opponents because of their intimate closeness. As it turns out to be, for the same reason the same term had been used to designate languages of Southern Yue origin in what has been classed Chinese dialects as previously mentioned.

Only under the premise that 'Sintic-Yue' is terminologically a linguistic entity with which this paper will make more sense when demonstrating a linguistic fact that, characteristically, Vietnamese is much more like a Chinese dialect with words similar to not only its etymology that includes its tonal system, phonology, syllabicity, peculiar expressions, lexical stems and morphemic suffixes, but also all linguistic areas of grammatical markups, classifiers, particles, instrumental prepositions, etc. along with all morpho-syllabic stems independently to make up a vast amount of new localized Vietnamese words, for example, 訂婚 dìnghūn ~ 'đámhỏi' (marrital engagement), 嫁娶證 jiàqǔzhèng ~ 'giấygiáthú' (marriage certificate), etc. Those linguistic attributes and traits between Vietnamese and Chinese are peculiar and they appear to be interchangeable like those of any Sinitic languages such as Cantonese and Fukienese among themselves. With such similarities historical linguists could tout them as integral parts that have made up Vietnamese in its wholeness and it could be grouped together with other southern Chinese dialects in the Sino-Tibetan family on same footing. With such recognition, the author would like to create a linguistic class by itself, the Sinitic-Yue linguistic branch, as illustrated in the previous chapter, that could be cascaded within the Sinitic linguistic sub-family to be on par with other 'Yue-rooted languages' into which even Cantonese or Fukienese, reciprocally, can also be grouped in both classes of Sinitic and Yue, beyond the boundary of Vietnamese.

That is to say, speculatively, in a limited sense we could extend further and identify the whole concept to cover linguistic roots of many indigenous languages spoken by many ethnic groups, descendants of the Yue 越 (or 粵) called BăiYuè (BáchViệt 百越), usually referred to as Nanman (南蠻 or 'Southern Barbarians') in ancient Chinese records, long before the emergence of the Han Dynasty. Descents of those Yue aborigines have long existed in history and, in our modern time, they are known as the Zhuang (壯族, Tráng or Nùng in V) — the largest one in terms of its population among other minorities still living in the southern part of China today — along with other ethnic groups such as as the Dai people currently living in mountainous regions of North Vietnam, Laos, Thailand — of which their racial stock is innovatively classed as of 'Austro-Thai' by Benedict (Benedict, 1975).

For the terminology "the Austroasiatic linguistic family", in order for the Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer theorization to hold its merits in our comparative review, it needs to fit into historical settings that would satisfy its both sides of the story of its and ours. The whole 'Austro-' perspective, continuant from the previous century, has led to the convergence of the notion that ancient Yue speakers largely could have been descended from a common ancestor who could come from Southeast Asia or even the southern hemisphere. Nevertheless, very recently archaeological findings have unveiled new artifacts of human skeletons dated more than 40,000 years old — much older than those 10,000 year old human bones found in Indonesian south — in an area 50 km southwestern from today's Beijing. The location implicates the possibility that all Asian humans might have originated from the northern sphere (北); hence, that provides some links to what is called as 'proto-Tai' prior and its Taic links to the arrival of nomadic proto-Tibetan people from the southwest region.

The term Taic (or proto-Daic and proto-Yue) is used to indicate the indigenous racial stock that once inhabited in the southern region of today's China and might have split up into many distinct ethnic goups, if the BaiYue (百越, or 'One Hundred Yue Tribes' as commonly called) recorded in early Chinese annals were truthful, which may include the Zhuang and Daic people (泰族) in our era. Besides, they have been identified with other natives in China South in habitats covering the vast region below the Yangtze River (揚子江, aka 長江 Changjiang) since the prehistoric times — like that of the Austroasic theory, this theorization is the only cases that is postulated on analogy and induction from historical records though — all areas south of its lower basin includes Anhui and Hebei provinces, and east to today's Jiangsu Province — where people speak the Wu dialect — and south all the way past Hunan and Guangxi provinces further to the south reaching the Red River Delta in northern Vietnam.

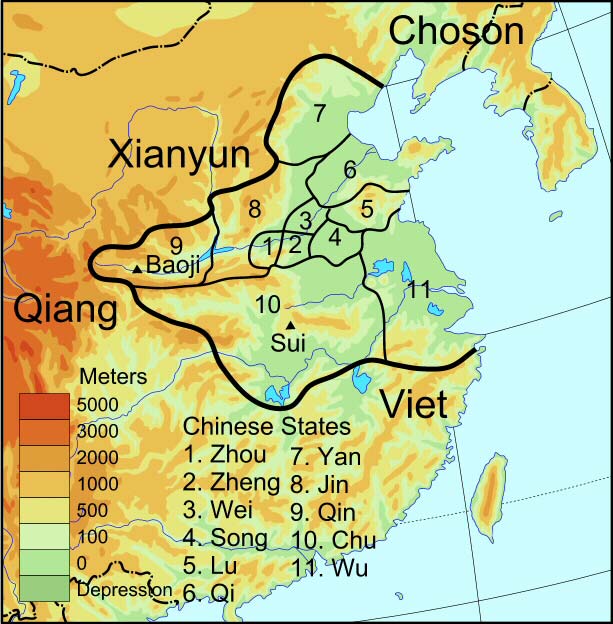

Map of the ancient states in China

Source: Multiple sources on the internet

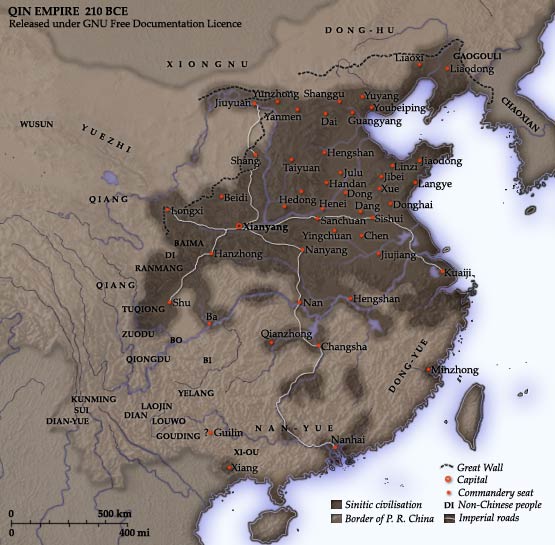

Figure 3B.1 - Map of the Qin Empire in ancient China

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Qin_Dynasty

So far, on the one hand, we have not brought 'the mystic foreign people in Bashu State 巴蜀 of ancient Sichuan' into the overall racial picture but traces of their presence found in archaeological excavation of artifacts show highly they had advanced civilization at some point in the remote past. Unfortunately, we do not evidences to connect those extinct people in the southwestern Sichuan with other ethnicities across China South, including the postulated Pro-Taic people. While the Chu subjects could be identified with neither the ancient Bashu nor Proto-Tibetan people, historically, we know that the makeups of the Chu populaces were mixed — consisting of ancient Taic people, i.e., forebears of the Daic and Yue branches — that gave birth to the historical Qin-Han people two centuries B.C. The proto-Taic people were also the ancestors of both the Taic subjects of Chu 楚 and the Yue populaces of the Zhou 周, Wu 吳, and Yue 越, who would later mixed with the former populace the earlier ancient Qin State 秦國 (778 – 207 B.C.) to make up the Chinese people. (Y) In other words, ethnologically, proto-Taic people had further diversed into smaller branches and evolved into different ethnic groups at earlier prehistoric period, of which each rising tribesmen would rule one of seven Yue states in later time (see map below) as recorded in Chinese history over the span of at least two millenia prior to the unification of the vast Qin Empire under the rule of Qin Shihuang (秦始皇), the first emperor of the unified 'China' and, later, the Western Han (西漢).

Following the unification after the Qin's total victory, all subjects of the other six states in the eastern part of today's China — that is, of the Chu 楚, Zhao 趙, Qi 齊, Jin 晉, Yan 燕, and Han 韓, which had priorly existed as vassal states of the Eastern Zhou (403 - 221 BC) — the people of which were direct descendants of "the proto-Chinese" {XYZ} who had come from the southwest made up the population of the subjects of the Qin State 秦國 (221- 206 B.C) and subsequently they merged with those Taic descendants of the Chu State to establish the Han Dynasty (漢朝, 206 B.C.–220 A.D.) and then mixed those people from the six other former states in the central mainland (Zhongyuan 中原) of the Middle Kingdom populace have become Zhongguoren (中國人) — finally, "the mixed-stock Chinese" people {X4Y6Z8H} — as they are being called today.

Figure 3B.2 - Map of the historical ancient Yue states

Source: Multiple sources in public domains on the internet

Map of the NanYue State in China South

Source: Modified map from http://en.wikipedia.org

The process Chinese immigrants from mainland of China to Vietnam happened in the same fashion that repeated to both indigenes with the biometrics {2YMK} and emigrants {4Y6Z8H} who had previously lived or already long resettled in the northern part of today's Vietnam around the Red River Delta Basin before foot soldiers of the Han Empire — that also consisted of Yue populace from those states that fell under the umbrella of Qin Dynasty in the earlier period — came to invade the ancient Vietnamese northern piece of land. All at the same time, war-savaged immigrants followed them and altogether they as the new settlers who mixed up with the locals and made up the population of the ancient Annam.

Throughout the periods of the Chinese expansion, for those early native Yue people, notably the Zhuang, the Dong, the Yao, or the Miao people (known as Mèo in Vietnam and Hmong in Laos), etc., who had not been able to put up with the process of integrating forces of the Han culture (Sinicization) in the mainland, they fled to mountainous hideouts. Over the time offsprings of those who remained there but uncollaborated with the new occupiers had been forced to emigrate out of the China South and fled southward into Giaochỉ 交趾 (Jiaozhi; later called 交州 Jiaozhou which was ancient Annam 安南) and their descendants later were mixed again with more racially-mixed immigrants continuing to come from the north.

Once having reached the outer region beyond new frontiers, those Han conquerors and colonists as sourjorners were mostly forced to have resettled therein forever to fulfill imperial China's 'national policy' that had been implemented as late as 787 in the Tang Dynasty (Bo Yang, Zizhi Tongjian, Vol. 56, p. 83). All new resettlers doubless were mixed up with the natives {2YMK} through intermarriages with local women — if there had been enough female matches for men at all — or with other waves of those mixed-stock Han immigrants {X4Y6Z8H} from the China North (華北 Huabei) and China South (華南 Huanan) who followed the footsteps of the Han infantrymen to safeguard new frontier prefecture called Annam, then there were born the local "Kinh" {4Y6Z8HMK} people — also known in modern Chinese as Jing 京 ethnicity, i.e., Vietnamese, — and the same trendy immigratory pattern recurred throughout the next two millenia well into our contemporary era, e.g., new chinatowns having sprung up around newly established plant enclosures throughout Vietnam in the last two decades. Undoubtedly their offsprings over the time had numerously multiplied and gave birth to the next generation one after another and they became a part of the population of the country and their descendants in turn made up majority of the Kinh nationals in modern Vietnam.

Outline of the isoglottal languages in China South

1.0 Taic languages

1.1 Austroasiatic linguistic family

1.1.1 Mon-Khmer languages

1.2 Yue languages

1.2.1 Zhuang language

1.2.2 Daic language

1.2.3 Miao languages

1.2.4 Maonan language

1.2.5 VietMuong languages

1.2.5.1 Muong dialects

1.2.5.2 Vietic language

1.2.6 Proto-Cantonese (NanYue)

1.2.7 Proto-Fukienese (MinYue)

1.2.8 etc.

1.3 Proto-Sinitic languages

1.4 Sinitic-Yue languages

1.4.1 Ancient Annamese

1.4.2 Sinitic-Vietnamese

1.4.3 Vietnamese

1.4.4 etc.

2.0 Sino-Tibetan linguistic family

2.1 Archaic Chinese

2.1.1 Old Chinese

2.2 Ancient Chinese

2.2.1 Chinese dialects (Fukienese, Wu dialects, etc)

2.3 Early Middle Chinese

2.4 Middle Chinese

2.4.1 Cantonese dialects

2.4.2 Sino-Vietnamese

2.4.3 etc.

2.5 Early Mandarin

2.6 Mandarin

2.6.1 Northwestern Mandarin

2.6.2 Putonghua

2.6.3 Northeastern Mandarin

2.6.4 Southwestern Mandarin

2.6.5 etc.

2.7 Cantonese

2.7.1. Guangzhou dialect

2.7.2. Taishan dialect

2.8 Fukienese

2.8.1. Xiamen dialect

2.8.2. Hainanese dialect

2.8.3. Chaozhou dialect

2.9 The Wu dialects

2.9.1. Wenzhou dialect

2.9.2. Shanghainese dialect

2.10 Etc.

Under such historical circumstances, languages in "the Austroasiatic linguistic family" {1.1} (a positional value for symbolistically weighed hierachy) had been formed out of Taic languages {1.0} some 6,000 years ago, long before the emergence of the Western Zhou (西周) Dynasty. In other words, they all had been stemmed from an ancestral proto-Taic linguistic form {1.0} supposedly spoken by the so-called "larger Taic indigenous people" and finally evolved themselves into linguistic forms of the Yue {1.2}, including those speeches currently spoken by the Zhuang, the Dai, the Miao, the Maonan, the Vietmuong, etc. {1.2.1, 1.2.2, 1.2.3, etc.}, while other branches had diverged into other Mon-Khmer languages included in what is now universally named as "the Austroasiatic linguistic family" {1.1.1, 1.1.2, 1.1.3, etc.}.

During the reigns of the Zhou kings, Taic glosses {1.0} had also found their way into, intertwined and interpolated, and merged with the Archaic Chinese (ArC) {2.1}, or Old Chinese (OC) {2.1.1}, including Ancient Chinese (AC) {2.2} of the Later-Han, since its break-off from the Sino-Tibetan route {2.0} and evolved itself independently (see Brodrick 1942, Norman 1988, Wiens 1967, FitzGerald 1972). (cf. Tibetan and Sinitic linguistic cluster as opposed to Mon-Khmer and VietMuong cluster) Variants of this early form of OC {2.1.1, 2.1.2, 2.1.3, etc.} later were brought by the 'Han' foot soldiers and emigrants to have gone south all the way to Annamese ("Tonkin") land and then blended well gradually with the Vietic language {1.2.5.2} after it had separated from the Viet-Muong group.

Symbolistically, in a broader sense, on the one hand, Austroasiatic languages (1.1} may have the same footing with properties overlapped inclusively or even mean the same thing as the Yue languages {1.2}, which is covered under the Taic stage {1.0} before the emergence of the historical Yue {1.2} language. The implication of the concept of the historical 'Yue' is that it does not include Vietnamese as having had a direct genetic affinity with the Mon-Khmer sub-family that is what the Austroasiatic hypothesis is all about {1.1); therefore, the concept of "Austroasiatic" is engrossed in a 'union' with "the Yue languages". What is known as the Austroasiatic linguistic family was postulated by its theorists as an ancestral form of the Mon-Khmer languages that gave birth to the proto-Vietmuong and the later Vietnamese as commonly referred to by modern linguists. In other word, they all are descendant languages under the larger ancestral Austroasiatic linguistic family and the Vietnamese language was descended directly from the Mon-Khmer linguistic branch. That is misleading.

Figure 3B.3 - Map of the historical ancient Yue migrations

Source: Multiple sources on the internet

In a broader sense, on the other hand, if we start out a premise for the Vietnamese language origin as it was descennded from the Taic family that will equally apply to all other linguistic groups such as Zhuang, Daic Miao, etc. {1.2.1, 1.2.2, 1.2.3...}, it could be postulated that the Vietmuong sub-family was a break-off from the "Yue" mainstream hundreds of years ago to form the Vietic language, given the existence of the former Muong linguistic remnants in Annamese. Such postulation then would conveniently put the Viet-Muong group under the Austroasiatic linguistic roof {1.1} on par with other Mon-Khmer daughter languages {1.1.1, 1.1.2, 1.1.3, etc.} as well, including Vietnamese, which would help match the commonly cited Mon-Khmer basic words only while at the same time maintaining etymologcal forms of the ancestral Yue {1.2} in the "Taic languages mainstream {1.0}. It is so said because it is much easier to find commonalities with Daic-Kadai than those of Mundaic languages in faraway in India (see Henri Maspero's "Les Langues Mounda" in Les Languaes du Monde. 1952. pp. 624-25.

Regarding cognateness of those basic words in Vietnamese and the Mon-Khmer languages, their etymology is not in diachronic connection with the Sinitic synchronizing patterns that we are dealing with here. In term of linguistic development, any Chinese traces in any Mon-Khmer languages, if any, are fairly recent, probably within the time frame of from 300 to 800 years ago, and could be borrowed via the North Vietnam's trade route. Per Ferlus,